In their new book, Practical Radicals: Seven Strategies to Change the World, Deepak Bhargava and Stephanie Luce offer what they say are “winning strategies, history and theory for a new generation of activists”.

Bhargava and Luce – professors at the City University of New York’s School of Labor and Urban Studies – emphasize that strategies can be taught to build successful movements. In their book, they detail seven tactics that have been successfully used to change the world: base-building, disruptive movements, narrative shift, electoral changes, inside-outside campaigns, momentum, and collective care.

Steven Greenhouse, a longtime labor reporter and senior fellow at the Century Foundation, conducted this Q&A. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Steven Greenhouse: Why did you write this book?

Deepak Bhargava: I was motivated by a sense of frustration about the state of strategy and strategic thinking among progressive movements. To win big changes on the major issues of the day, we’re going to need to up our game substantially. I wanted to explain: where oppressed groups managed to achieve big gains despite incredible asymmetries in resources, how did they manage to do that?

Greenhouse: Your book seems to be saying that the progressive movement is underperforming, perhaps even failing. How so?

Bhargava: There are examples of breakthrough success in progressive movements that we need to understand better. The book features some of the successes we found the most inspiring, like the movement to abolish slavery and contemporary examples like the Fight for $15 or the campaign to divest from fossil fuels.

Jim Obergefell, named plaintiff in the Obergefell v Hodges case, bottom center, speaks to the media after the supreme court’s same-sex marriage ruling on 26 June 2015. Bloomberg/Getty Images

The default position in progressive movements is often to organize toward tactics, like noisy protests, that may or may not have any impact on decision-makers. Sometimes we just keep doing the same thing over and over, and that’s frustrating. We have to hold ourselves to a higher standard.

Greenhouse: Why is base-building the first strategy you focus on in your book?

Stephanie Luce: Base-building is the fundamental power that underdogs have. It’s based on the power of numbers, the power to come together, whether in the form of a labor union, community organization or tenant’s rights organization. That’s a bit of the foundation for any of the other strategies. To pull off a successful strike, you need to have built a solid organization among your coworkers.

Greenhouse: Narrative shift is another strategy you focus on. Why is that important and what are some examples of how narrative shift has succeeded?

Luce: Sometimes narrative strategy is taken to mean just writing a good slogan or press release. We came to see it as something much deeper, as organizing in a way that listens to people, understands their history and identity and helps people shape the common sense of what’s going on – understanding that there are problems in the world that you’re struggling with, eg the economy’s bad, but what is the root cause of that? What are the villains we’re fighting against? The narrative shift approach is about making meaning of larger trends in society.

As for examples, we talk about Occupy Wall Street and the marriage equality movement. A lot of people think of Occupy Wall Street as a protest, but its largest impact was changing the narrative, changing the understanding of what was the cause of the 2008 economic crisis and what are some ways out of that crisis, so that we’re not just blaming low-income homeowners. Occupy developed a narrative about the 1% and 99%, and that helped reshape the notion of who is the agent of change.

Greenhouse: A huge problem progressives face is that the other side has so much money, corporate money, Koch network money. How can the group that you call underdogs overcome that?

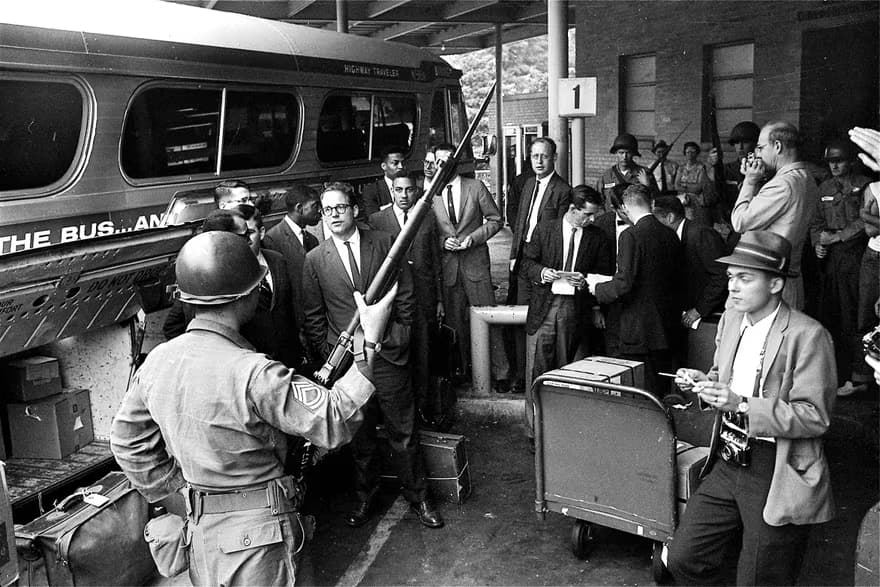

Bhargava: When underdogs win, they do so by using multiple sources of power. The most important of those is people power, what we call solidarity power. There are more underdogs than overdogs in almost any situation, but it’s also crucial for underdogs to disrupt. By that we mean not just to protest, although protests can be very important, but to sometimes stop the functioning of an unjust system. This is what workers do when they go out on strike. It’s what the Freedom Riders did when they disrupted segregated interstate travel. It involves everyday people taking big risks. Without that, it’s often very difficult to get major social change.

Greenhouse: Another strategy you discuss is the momentum model. How does that differ from base-building?

Bhargava: Momentum is both ancient and new. It’s new in the sense that online technologies have enabled activists to assemble large numbers of people very quickly around a flashpoint that stirs people’s emotions. Sometimes those flashpoints are unplanned, as with the murder of George Floyd. Sometimes people can stage big moments, as environmental activists did when they organized arrests at the Obama White House to protest the Keystone XL pipeline. Those moments are opportunities to gather thousands of activists together, not just for a one-off protest, but to train them in a vision and techniques of how to launch campaigns when they go back home. The momentum model combines scale with depth and trying to move agendas at the local level.

A busload of Freedom Riders, including professors and students, arrives in Montgomery, Alabama, on 24 May 1961. Perry Aycock/AP

Greenhouse: The United Auto Workers recently pulled off one of the most successful strikes in decades. Did they use any of your seven strategies?

Luce: They certainly used disruptive power. They used the power to shut down the auto companies and make them suffer and lose a lot of money. That disruptive power also rested on solidarity power because they had to make sure they had cohesion within the union. People ready to strike have each other’s backs.

Now that they’re moving from the strike to an ambitious organizing drive, they’ll be using both the base-building approach and the momentum approach in trying to organize auto plants over the coming months.

Greenhouse: One of the biggest challenges facing labor right now is that more than a year after workers at Starbucks, Amazon, Trader Joe’s, REI, Chipotle and Apple first unionized, none of them have first contracts. What do you recommend doing about this?

Luce: This is an example where we need a major disruption of corporate power. The deck is stacked against these workers. They don’t have the same kind of economic power and disruptive power the autoworkers have. They don’t have the ability to strike in strategic ways that shut the companies down so drastically. So they’re going to have to rely on other forms of alliances, other partners that can aggregate power and disrupt economic power. That could be broader circles of unions and workers and non-union workers coming together. It might be community partners.

Greenhouse: Our nation will hold unusually important elections in November 2024. You talk about electoral change as a strategy. What strategies do you recommend for the 2024 elections?

UAW wants to unionize Tesla. It faces a tough and high-profile battle with Musk Read more

Bhargava: Electoral strategies that are only about candidates are not likely to succeed. There is cynicism about politics because it hasn’t consistently delivered material improvement in people’s lives. Engaging in elections requires a long-term organizing approach. Our book features examples where electoral strategies are driven by community groups and unions that aren’t just inviting people to vote, but are inviting people to be part of organizations to work on the issues they care most about. That community-centered approach is going to be even more important in 2024 when many communities are afflicted by despair or a deep distrust of establishment political parties. That model will become central if we’re to get the kind of turnout, particularly from young people and communities of color, that we all hope for.

Greenhouse: What do you hope to achieve with this book, beyond selling thousands of copies?

Bhargava: We argue that great strategists are made, not born. We think the times are right for a broad scale investment in thousands of everyday people to be the Ella Bakers and Bayard Rustins of our own age. That kind of strategic rigor needs to be taught on a mass scale. The challenges we face are so large and daunting that without many thousands of people capable of understanding the power relationships in our society and what the leverage points are, we aren’t going to win. A big hope of this book is that it contributes to democratizing great strategy, that it makes strategy accessible to many more people in the years to come.

Steven Greenhouse is a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, where he writes about wages and working conditions, labor organizing, and other workplace issues. Before coming to The Century Foundation, he was a reporter for the New York Times for thirty-one years, spending his last nineteen years there as its labor and workplace reporter, before retiring from the paper in December 2014. He is the author of Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present, and Future of American Labor, published by Alfred A. Knopf in 2019.

Deepak Bhargava is a policy expert on issues of poverty, economic justice, racial equity, and immigration at CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies. He has extensive practical experience in community organizing, leadership development, social movements, progressive strategy, issue campaigns, coalition building and voter mobilization.

Prior to joining SLU, he was President and Executive Director of Community Change and Community Change Action for 16 years, two of the premier national organizations supporting grassroots community organizing in low-income communities of color in the United States. He has trained and mentored hundreds of leaders who play key roles in progressive organizations and social justice movements, and worked to establish important labor-community partnerships at the national level on issues such as immigration reform, health care, and fiscal policy.

Stephanie Luce is a Professor of Labor Studies at the School of Labor and Urban Studies, and a Professor of Sociology at the Graduate Center, City University of New York (CUNY). She received her BA at the University of California, Davis and both her PhD in sociology and her MA in industrial relations from the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Best known for her research on living wage campaigns and movements, she is the author of Fighting for a Living Wage, and co-author of The Living Wage: Building a Fair Economy, and The Measure of Fairness. She is also author of Labor Movements: Global Perspectives.

A message from Betsy Reed, Editor, Guardian, U.S.:

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I wanted to ask if you would consider supporting the Guardian’s journalism as we prepare for one of the most consequential news cycles of our lifetimes. We need your help to raise $1.5m to fund our reporting in 2024.

From Elon Musk to the Murdochs, a small number of billionaire owners have a powerful hold on so much of the information that reaches the public about what’s happening in the world. The Guardian is different. We have no billionaire owner or shareholders to consider. Our journalism is produced to serve the public interest – not profit motives.

And we avoid the trap that befalls much US media – the tendency, born of a desire to please all sides, to engage in false equivalence in the name of neutrality. While fairness guides everything we do, we know there is a right and a wrong position in the fight against racism and for reproductive justice. When we report on issues like the climate crisis, we’re not afraid to name who is responsible. And as a global news organization, we’re able to provide a fresh, outsider perspective on US politics – one so often missing from the insular American media bubble.

Around the world, readers can access the Guardian’s paywall-free journalism because of our unique reader-supported model. That’s because of people like you. Our readers keep us independent, beholden to no outside influence and accessible to everyone – whether they can afford to pay for news, or not.

If you can, please consider supporting us with a year-end gift. First-time supporters give an average of $42, but every dollar makes a difference. Thank you.

Spread the word