When a mountain-size slab of space rock rammed into the Yucatán Peninsula 66 million years ago, the fallout was apocalyptic. Tsunamis washed away coastlines, raging fires engulfed forests and dust and debris blotted out the sun for months. Roughly three-fourths of the planet’s species, most notably non-avian dinosaurs, were wiped out.

But one group appears to have weathered the maelstrom. In a paper published Wednesday in the journal Biology Letters, researchers present evidence that flowering plants survived the Cretaceous-Paleogene, or K-Pg, mass extinction relatively unscathed compared with other living things on Earth at the time. The catastrophe may have even helped flowering plants blossom into the dominant green things they are today.

“It’s just bizarre to think that flowering plants survived K-Pg when dinosaurs didn’t,” said Jamie Thompson, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Bath and one of the authors of the study.

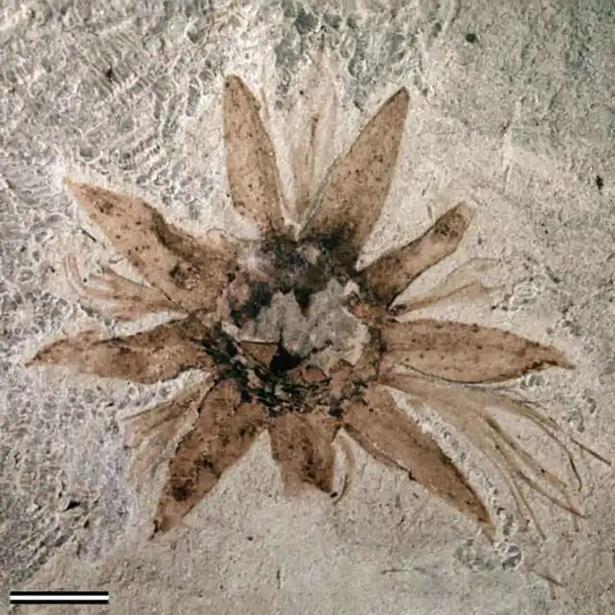

Flowering plants are known to scientists as angiosperms. They originated in the early Cretaceous, and were often overshadowed by older groups like conifers and ferns. But they rapidly diversified as mass extinction loomed.

To determine how flowering plants fared during the K-Pg extinction event, Dr. Thompson teamed up with Santiago Ramírez-Barahona, an evolutionary geneticist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The pair were initially hindered by a lack of fossil flowers, which are scarce compared with fossilized bones. Some of the largest angiosperm lineages today, like orchids, barely show up in the fossil record.

To uncover the evolutionary insights missing from the fossil record, the researchers analyzed two evolutionary trees containing more than 100,000 species of living angiosperms. These sprawling data sets, known as phylogenies, were calibrated using molecular clues that allow scientists to group related species together and determine when certain lineages diverged. Together, the phylogenies lay out an evolutionary timeline of when the ancestors of modern angiosperm lineages emerged and when they died out.

The researchers discovered something surprising. While many angiosperm species died out with the dinosaurs, pterosaurs and marine reptiles — especially those living near the asteroid impact crater — the larger lineages of flowering plants survived the extinction event and exhibited a relatively constant rate of extinction through time.

“I think that is actually in perfect step with the plant fossil record,” said Paige Wilson Deibel, a paleobotanist at the Burke Museum in Seattle who studies fossils from the K-Pg boundary in northeastern Montana and was not involved in the new study. “There is really high species-level extinction but the major lineages all seem to have survived.”

This contrasts starkly with the evolutionary tree of dinosaurs. “Non-avian dinosaurs lost so many species, they lost entire lineages, which we don’t see in angiosperms,” Dr. Thompson said.

While more work is needed to determine how angiosperms survived one of the deadliest extinctions in Earth’s history, the researchers posit that their adaptability played a role. Because flowering plants are pollinated by both insects and wind, they have significant reproductive flexibility. Their vast diversity — by the end of the Cretaceous, grasses, sycamore and magnolia trees, and aquatic waterlilies had all appeared — may have also helped them survive the devastation.

As Earth’s climate stabilized and life recovered, flowering plants took over terrestrial ecosystems. In 2021, researchers comparing Colombian fossils from before and after the K-Pg boundary found that the extinction allowed angiosperms to dominate. This led to the first rainforests, which remain hotbeds of flowering plant diversity.

Dr. Ramírez-Barahona said this trend likely occurred in ancient ecosystems worldwide. “Before and after the K-Pg impact the whole ecological composition changed,” he said. “They restructured themselves into these new flowering ecosystems.” Today, nearly 80 percent of all terrestrial plants are angiosperms.

In this way the impact that doomed the dinosaurs gave rise to modern ecosystems. Instead of giant reptiles, these habitats were populated by mammals, who had persisted through the mass extinction along with flowering plants and were primed for a similar explosion in diversity.

After the K-Pg boundary, “we’re starting to see plants and animals that we recognize,” Dr. Wilson Deibel said. “It’s in this really dynamic time of giant environmental disasters and mass extinctions that the environment becomes analogous to what we see today.”

Jack Tamisiea is a science writer based in Washington D.C. who covers natural history and the environment. He loves uncovering new stories from old museum collections and highlighting the quirks of both strange and familiar species. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, National Geographic, Scientific American, The Atlantic, Hakai Magazine, Johns Hopkins Magazine, Smithsonian Magazine and other popular science publications.

Jack graduated from the University of Southern California where he studied Environmental Studies and English and recently received a Masters in Science Writing at Johns Hopkins University, where he received the David Everett Award for Outstanding Thesis for his collection, “Pickled in Jars and Crammed into Drawers: Uncovering new stories from old museum collections.”

He has always been fascinated by fossils, reptiles and amphibians, and is passionate about capturing their curious nature through writing, photography and art. No matter where he goes, he’s always on the lookout for a natural history museum or national park!

The New York Times is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2022 to comprise 740,000 paid print subscribers, and 8.6 million paid digital subscribers. Founded in 1851 as the New-York Daily Times, it is published by The New York Times Company.

The “Crisis in Cosmology” Is Pure Exaggeration

There are a few clues that the Universe isn't completely adding up. Even so, the standard model of cosmology holds up stronger than ever.

Ethan Siegel

Starts with a Bang/Big Think

September 6, 2023

Spread the word