The Sum of Us

What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together

By Heather McGhee

One World

ISBN 9780525509561

So many articles written in the past year bear portentous titles: “You’re Likely to Get the Coronavirus,” “Everything is Broken,” “Private Schools are Indefensible,” “The Last Children of Down Syndrome.”

All this reading was educational, but none gave me hope. They counseled me against taking a cruise or leaving the house. They encouraged me to bemoan the morally impoverished states of American education, health care, media, and government, and set me to staring mournfully at my happy-go-lucky nephew with Down Syndrome.

But I’ve just read something different, a book that articulates our problems with compassion and kindness, and inspires me to dig deep and seek out difficult conversations. I agree with Ibram X. Kendi, who wrote of Heather McGhee’s “The Sum of Us,” “This is the book I’ve been waiting for.” We are living through an age in which white privilege is beginning to get its comeuppance. “The Sum of Us” explains why that’s a good, necessary thing, and not to be feared. Life will be better for all of us if we live as though we’re all actually, truly in this together.

When McGhee asks, at the outset, “Why can’t Americans have nice things?” she means the basics: good roads, well-funded schools, affordable health care, decent housing, clear air and water, jobs that pay a living wage. We can’t have nice things because white America would rather go without than invite Black America in. Over the past five decades, life has increasingly come to be seen as a zero-sum competition. We’ve been deluded to believe that what’s provided for one group must necessarily be denied another. The richest nation on earth suffers from a scarcity mindset, because of racism.

It was not always so. “In the mid-1960s,” writes McGhee, “the American Dream was as easy to achieve as it ever was, or has been since, with good union jobs, subsidized home ownership, strong financial protections, a high minimum wage, and a high tax rate that funded American research, infrastructure, and education.” An economy that looked, as she describes it, like a football — “fat in the middle” and thin at both ends. Now, 50 years later, it looks like a bow tie, with a hollowed-out middle, and “bulging ends of high- and low-income households.”

Thirty-one million Americans have no health care. Home ownership rates are falling. Forty percent of Americans can’t afford the basic necessities of life. The air quality gets worse every year, and public schools less equitable with each passing decade. The richest one percent of Americans own as much as the entire middle class combined. We behave, in McGhee’s words, “singularly stingy toward ourselves,” with our government spending less on us per capita than Latvia and Estonia.

Why can’t we be more like the Scandinavian countries, with their enviable education systems, parental leave benefits, and overall quality of life? Because, argues McGhee, “unlike the United States, Finland didn’t have mass slavery and genocide to cut their empathic cord at the country’s birth.” Racism hurts everyone.

McGhee spent most of her career at Demos, a progressive “think and do tank,” where she tried to influence the course of human events by crafting or influencing public policy, putting faith in the transformative power of legislation. She eventually realized they were putting the cart before the horse. Policy shifts, if they are to create lasting change, must flow from, not anticipate, shifts in public opinion. So, McGhee left Demos to set out on a quest to understand what Americans believe, and why.

She brings many Black and white voices into her engaging, swift-moving narrative. Among the more surprising of these is Hinton Rowan Helper, a white racist abolitionist. He found the institution of slavery unconscionable not because of the harm it did Black folks, but because of the harm it did white people. In 1857, he self-published the book “The Impending Crisis of the South: How to Meet It” to lay out his case. He argued that an economy based on slavery held the South back, economically and culturally.

Helper compared Northern and Southern states, counting 393 public libraries in Pennsylvania, versus 26 in South Carolina, and 2,382 public schools in New Hampshire, versus 782 in Mississippi. These stark contrasts so damaged the South’s self-image that the book was banned in certain places, and three men in Arkansas were hanged for owning it. But Helper was on to something. Today, nine out of the 10 poorest, seven out of the 10 most poorly-educated, and nine out of the 10 most unhealthy states are Southern states in which slavery thrived.

I bristle when I hear white people claim “I don’t have a racist bone in my body” or “I don’t see race.” Until reading “The Sum of Us,” however, I had trouble articulating why these assertions sounded so ridiculous. I see things better now. Racism is not a personal failing, it’s a systemic construct. We don’t get to opt out, because it’s been imposed on us. It’s not about you; it’s the story of us. As McGhee put it, “Blindness to race is blindness to racism,” and if you’re blind to racism, then you must be simply blind.

Also due for a debunking is the meritocratic claim of “I pulled myself up by my own bootstraps. No one ever gave me a handout.” White people like me have been getting handouts since the day we landed on these shores. We were given a leg-up from those who came before us. Government policy and public investment enabled us to own land and purchase homes. We received free college educations that enabled us to join the professional class, and we voted without interference. All these ingredients of the American Dream were denied to Black people, who were liberated without a penny, without education, and without tethers connecting them to the free world.

A founding denial was the Homestead Act of 1862, wherein more than a million and half white people were granted free land west of the Mississippi River. By contrast, fewer than 6,000 newly free Black people were able to take advantage of the Southern Homestead Act. The Homestead Acts are estimated to have resulted in 46 million propertied white people alive today, fully one quarter of the American population. Historian Keri Leigh Merritt writes: “The Homestead Acts were unquestionably the most extensive, radical, redistributive governmental policy in U.S. history.”

In the 20th century, government big and small excluded Blacks from the life-changing assistance granted to white citizens. Through redlining, Black people were denied loans to buy or improve their houses. The government subsidized private developers to create the modern suburb, but these were closed off to Black would-be homeowners through “whites only” clauses in housing contracts. Black people were likewise mostly denied the incalculable higher education benefits created by the GI Bill that “catapulted a generation of men into professional careers.” All this bounty conferred on white people, “an elevated status, which seemed natural, and almost innate.” Whites received both entrée into the upper echelons of wealth and prestige, and the illusion of having gotten there solely by dint of their own hard work and racial superiority.

The changes wrought by the Civil Rights movement ushered in a new, less overt racism, which Republican strategist Lee Atwater explained in a 1981 interview. “You start out in 1954 by saying ‘[n-word, n-word, n-word]’. By 1968, you can’t say ‘[n-word]’. That hurts you, backfires. So you say stuff like ‘forced bussing,’ ‘states’ rights,’ all that stuff, and you’re getting so abstract. Now you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things, and a byproduct of them is Blacks get hurt worse than whites.”

McGhee’s book was published before the latest such outrage. Today, Georgia’s Republican party is pushing through legislation that would make voting in that state absurdly difficult, in a cynical pretense of protecting the system from non-existent fraud. Black people, the ones who turned out in record numbers in the last election, will be hurt the worst by the law, though, like so much racist policy, it would do nothing to help white voters, either.

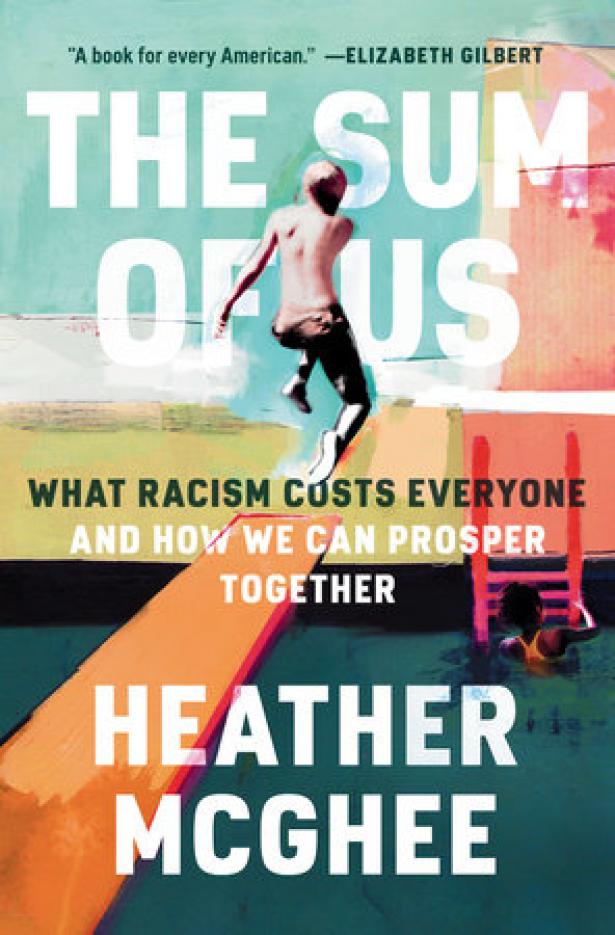

The image on the cover of “The Sum of Us” is not of a house or a workplace or a hall of government. It’s of a child jumping off a diving board. In the 1920s, town and cities saw, in the creation of enormous public swimming pools, an opportunity to promote the “Americanizing project.” There, in our bathing suits, sharing an intimate activity, we’d create a literal “melting pot.” But, once these public goods were integrated, the white public cleared out, retreating to private clubs. McGhee paints a scene of her visit to the site of what used to be the Oak Park public pool, in Montgomery, Alabama. Rather than comply with integration, public officials drained the pool and filled it with dirt. The author couldn’t even tell where the pool had once been.

The “draining the pool” metaphor applies well to our public schooling woes. In the seven decades since the Supreme Court decided against “separate but equal” in Brown v. Board of Education, our schools have not been transformed into “together and equal.” Today, two in five Black and Brown students attend schools that are more than 90 percent non-white, the majority of public school students are children of color, and almost half of private school students attend nearly all-white schools. Meanwhile, “good” public schools increasingly mean rich, and white. McGhee quotes from ATTOM data, which calculated that “someone with average wages could not afford to live in 65 percent of the zip codes with highly-rated elementary schools.”

This, she says, is a cost of racism, a “cost of fear itself. White parents are paying for their fear, because they’re assuming that white-dominant schools are worth the cost to their white children. Essentially, that segregated schools are best.”

The passages in the book which will stay with me longest are where McGhee turns subversive, and upends the meaning of a “good education.”

What if, she asks, we measured the quality of a school by how integrated it was, rather than by its standardized test scores? Integration, after all, confers a host of tangible educational benefits on all students. There is the obvious boost in cultural competency, a natural by-product of working and playing alongside people of diverse backgrounds, skills which will be increasingly important as we approach the time when whites will be in the minority.

“But their [students’] minds are also improved when it comes to critical thinking and problem-solving. Exposure to multiple viewpoints leads to more flexible and creative thinking, and greater ability to solve problems.”

Critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, flexibility, and ease of cross-cultural communication also happen to line up nicely with the “21st Century skills” students will need in order to succeed, in the traditional sense, in the information age.

Traditional parental aspirations haven’t caught up to the 21st century yet, however. In September, I wrote a letter requesting support for a remote learning school for the children of essentials workers, and briefly addressed this issue. “Upwardly mobile American parents have come to think of education primarily in sports terms,” I wrote. “What combination of classes and enrichment is going to get my kids over the finish line first? What do I have to do to help them win? … Isn’t this what’s behind much of the concern among privileged parents about children ‘falling behind’ during the COVID-19 pandemic? Who it is we’re afraid they are falling behind? Who do they need to stay ahead of? If my kid is ‘ahead,’ whose needs did he disregard to get there?”

“The Sum of Us” answers this last question decisively, and devastatingly.

Spread the word