Dr. Yuki Miyamoto, Ph.D. is Professor of Religious Studies and Director of the Humanities Center at DePaul University. She frequently leads student tours to Hiroshima and Nagasaki and has been appointed a Nagasaki Peace Correspondent in 2010 and a Hiroshima Peace Ambassador in 2011. Among her many scholarly publications on nuclear and environmental ethics are Beyond the Mushroom Cloud: Commemoration, Religion, and Responsibility after Hiroshima and A World Otherwise: Environmental Praxis in Minamata.

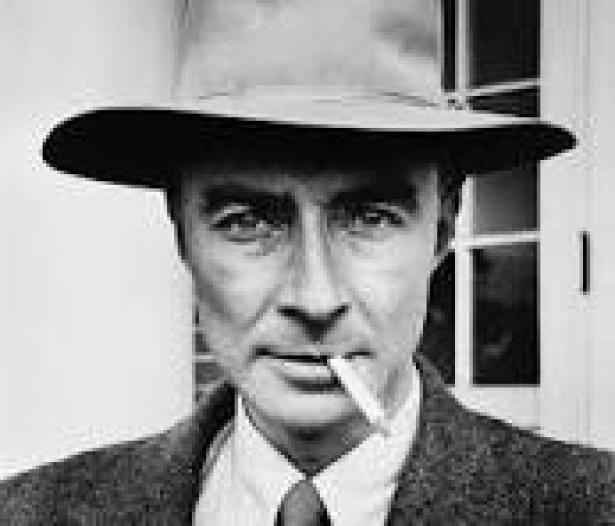

Fitzgerald: Last year, Oppenheimer made a big splash at the box office. In the U.S. alone, it grossed over 325 million dollars. What did you think of the response to the film?

Miyamoto: It was impressive, given the three-hour duration of the film and the subject matter. I never would have expected a film about the effort to make the first atomic bomb and the theoretical physicist who headed up that effort to be so popular. It hyped the youth culture with a new word—“Barbenheimer”—combining with the title of another megahit of the summer, Barbie. I appreciated that the film sparked interest in nuclear weapons among youth and young adults while rekindling the conversation among others.

Fitzgerald: What are some of the historical facts that you consider important for younger or less knowledgeable viewers to take away from the film?

Miyamoto: I still encounter students who have learned that the atomic bombing was in retaliation for the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. However, the plan of the Manhattan Project had been conceptualized in the summer of 1941, and the budget had passed Congress a day before the Pearl Harbor attack. The Nazis had given up their atomic bomb project in 1942 due to the difficulty of obtaining a large amount of uranium, as the result of the US having secured the uranium route in the Belgian Congo. Although the US officially learned about Germany’s abandonment of the atomic bomb project in late 1944, other sources suggest that the US had known about the cessation of the German a-bomb project much earlier. Yet the Los Alamos lab started operating in 1943.

The film depicted some controversy that erupted at the lab after scientists heard about the defeat of Germany. Oppenheimer was adamant about continuing the project. Certainly, he was later shocked by the scale of destruction at Alamogordo and was agonized over the devastation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He opposed furthering the project to create a hydrogen bomb. However, there is no record of him opposing the subsequent A-bomb tests in Nevada and elsewhere, totaling over 900, and that puzzles me.

Taking these depictions into consideration, the film poses important questions. First, it questions the category of science, which, despite the intentions of many well-meaning scientists who pursue truth, is too often involved and even manipulated by the political agenda of the time. Second, the film addresses scientists' responsibility. What kind of actions should be taken when scientists invent something akin to a "weapon of genocide," as referred to in the movie?

I cannot help thinking...is this the film that we need the most right now? Is this the perspective from which we should learn.

Fitzgerald: At its core, Oppenheimer is a biopic that focuses on the man himself. At the same time, you have reservations about the film. What are they?

Miyamoto: I cannot help thinking...is this the film that we need the most right now? Is this the perspective from which we should learn. The film, based upon American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, describes J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life, highlights him leading the Manhattan Project to success and his subsequent persecution by the Red Scare. In one of the climactic scenes of the film, Oppenheimer, witnessing the power he had unleashed, murmured, “I am become Death,” though it is unfortunate that the birth of the weapon of mass destruction was associated with the Hindu text Bhagavad Gita. After being engaged in the project for a few years, for the first time, he was finally struck by the reality of what he was doing.

It is important to humanize Oppenheimer, considering his hardships stemming from antisemitism and the Red Scare, but his suffering is quite different from that of those who endured the consequences of the Manhattan Project. The victims in Hiroshima and Nagasaki include the former colonial subjects, Korean victims, political dissidents, and POWs. Furthermore, I also would include the uranium miners in Belgium Congo, Canada, and the American West, the 13,000 New Mexicans living within a 50-mile radius of the Alamogordo test site, a group of girls camping 37 miles away from the hypocenter, and the Pueblo people who still struggle against contamination from the Los Alamos laboratory. I wonder when their suffering will receive attention and medical care, and when they will become humanized as this film humanizes Oppenheimer.

Fitzgerald: And I know that for you, Dr. Miyamoto, this is a very personal reality, one that has directly affected your family.

Miyamoto: Yes, my mother was 6 years old and a mile away from the hypocenter at the time of the Hiroshima bombing. She didn’t tell me about her experiences, but I witnessed her series of illnesses while I grew up. She suffered from Ménière's disease in her 30s, received a “blood booster” shot every other week as she was unable to produce healthy blood in her 40s, and had cancer in her 50s. She passed away at the age of 62.

My cousin was the daughter of a Hiroshima bomb sufferer. She also had an illness of the immune system in her 30s. She was bedridden for almost 20 years and passed away in her 50s. Many daughters and sons of the victims have been affected by their parents’ exposure to radiation.

Hiroshima sufferer Nakazawa Keiji drew on his and others’ experiences of the atomic bombing in a very approachable form of graphic novel, Hadashi no Gen, or the Barefoot Gen. In these volumes, which are available in English, he describes the violent nature of the Japanese military regime, the oppressed colonial subjects from Korea, and the shortage of food, clothes, and almost all materials that people need for everyday life. He also recounted the horrors of the atomic attack--the bodies burned beyond recognition, the decomposed and swollen bodies floating in the rivers, and the stench that filled the city. He also wrote about the long-term aftermath of the bombing. Orphans were used as pawns by the yakuza, the Japanese mafia, the only people who took them in. People had radiation sickness and died years after, and others were shunned and discriminated against by the fellow Japanese citizens because they were “tainted” with radiation.

These are the sufferings that Oppenheimer wasn’t even able to imagine and that the film fails to include.

Fitzgerald: Given all that you have said about the film, is there anything further you would like to highlight?

Miyamoto: I would like to emphasize that the film accurately depicts the atomic bomb as a weapon of mass destruction and genocide. It's crucial that we acknowledge the seriousness of what we are engaging with here. For example, Zyklon B, used at Auschwitz, is also a tool of mass destruction that irreversibly altered people's way of life. No one would produce a movie depicting scientists whose invention led to such devastation, let alone consume it as entertainment. I hope this movie will spark a more serious discussion of the consequences of the invention of the atomic bomb, as people are still suffering from its effects. We should not simply consume this event of mass destruction but rather confront its ongoing impact.

Frank T. Fitzgerald is a long-time social justice and peace activist and a retired sociology professor. He has written two books on the Cuban Revolution and numerous articles on politics and society. In recent years, he has worked as a non-veteran member of Veterans for Peace and as a member of the editorial board of the journal Science & Society. He can be reached at fitzgerf@icloud.com

The opinions expressed here are solely the author's and do not reflect the opinions or beliefs of the Hollywood Progressive.

Spread the word