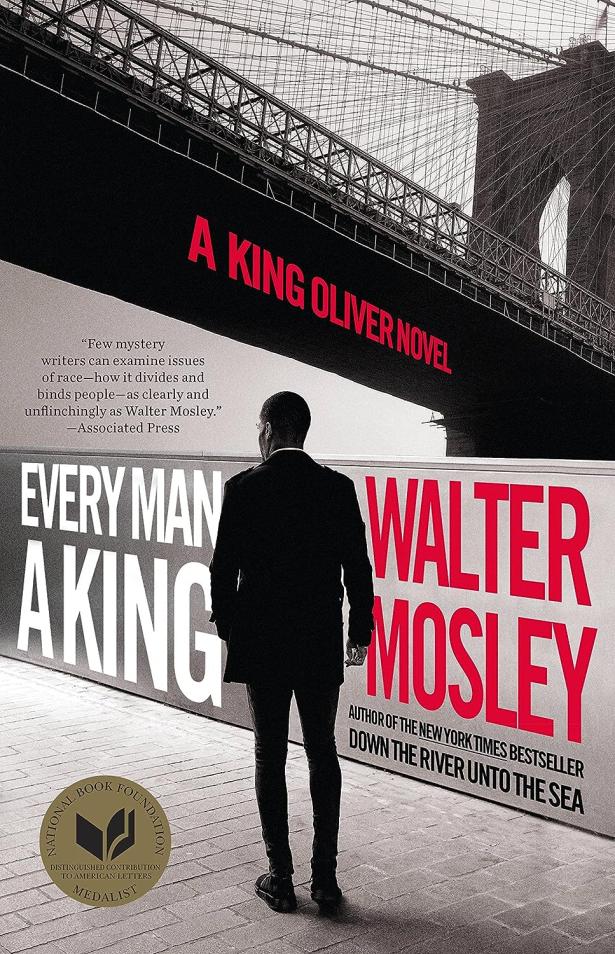

Every Man a King

A King Oliver Novel

Walter Mosley

Mulholland Books

ISBN-13: 9780316460217

The title of Walter Mosley’s provocative new novel, “Every Man a King,” is a motto with a violent history. It was the catchphrase of the firebrand Louisiana populist Huey Long, who might have challenged Franklin Roosevelt from the left in 1936, were he not assassinated first.

These words — a cry for equality from a bygone era — are a snug fit for Mosley’s novel, which skitters across the spectrum between orthodox and radical like a polygraph needle wired to a nervy accomplice.

The narrative begins with Joe King Oliver, a Black ex-cop and private detective in New York, driving uptown to meet a client at a palatial estate overlooking the Hudson River. The client is Roger Ferris, an enormously rich old white guy. Roger is the boyfriend of Joe’s feisty grandmother, Brenda, whose parents were sharecroppers.

Roger asks Joe to investigate what appears to be a government kidnapping. A man named Alfred Xavier Quiller has been unduly jailed in a secret cell on Rikers Island. Quiller is a noted inventor, a “natural-born genius,” and a manifesto-penning icon of white nationalism. Jillionaire Roger claims to abhor Quiller’s politics, but, he intones, “the betrayal of our civil rights is a crime worse than any he’s being held for.”

Freedoms betrayed, classes divided, races at war — such heady themes lace the length of Mosley’s 46th novel. Fans of his Easy Rawlins and Leonid McGill series will not be disappointed, for we remain in the realm of deliciously gritty noir. There will be cold-cocks and gunfights and stakeouts. There will be tough-talking heavies named Rembert Cormody and D’Artagnan Aramois, formidable femmes called Amethyst Banks and Minta Kraft.

I was struggling to update my corkboard when I read this exquisitely pulpy line: “Lawler was a New York blue blood who married a nouveau riche nobody named Constantine Psomas — a.k.a. the can man.” Warmth filled my guts like whiskey. I didn’t need a map. Mosley was driving me to Rikers in a cream-colored Bianchina, and Mingus was playing on the stereo. I was along for the ride.

As readers learned in “Down the River Unto the Sea,” the 2018 novel in which Joe King Oliver first appeared, Mosley’s latest private eye has spent some time on Rikers himself. A decade ago, Joe was the rare clean cop. Framed by corrupt colleagues, he spent torturous months in solitary. When he re-enters the prison in the new book to find Quiller, his trauma is palpable: “My left hand was shaking slightly and my feet felt as if they were growing toe roots. … The sweating started when the iron door slammed shut.”

This back story brings the novel’s high-tone themes to life. Joe’s experience of wrongful incarceration forms a psychic bond between him and the racist ideologue he’s been employed to rescue. As the story unfolds, prison contractors emerge as central antagonists — alongside alt-right militias and Russian oil-trading syndicates. Did I mention that Joe’s ex-wife’s husband, a chiseled Wall Street swindler named Coleman Tesserat, has also been thrown in prison?

Joe takes on this second case out of consideration to his brilliant daughter, Aja-Denise, Tesserat’s stepchild. As the two investigations tangle together, the narrative threads become difficult to follow. But Mosley’s labyrinth leads Joe to a delightful variety of artfully drawn settings. One minute, he’s outwitting oligarchs in the Obsidian Club, a gleaming Midtown billionaires’ lounge; the next, he’s bantering with a sex worker in hardscrabble Brownsville, “a place where children learn lessons that they spend the rest of their lives trying to forget.”

All this is classic Mosley, a master of the hard-boiled style that Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett pioneered in the 1930s. The byzantine plot, the suave private eye, all the uncanny similes; it’s a cocktail that skilled authors will serve as long as bartenders are still pouring Negronis. At times, Mosley seems reluctant to part with outmoded aspects of the formula: Quiller’s fatale wife has a figure “reminiscent of a Playboy bunny of the late ’60s — opulent, impossible”; Joe describes a dandy he encounters as “what once might have been called an effeminate Black man.” When Joe gruffly resigns himself to evolving social mores, I wondered whether I was hearing the voice of the 71-year-old author and not the 44-year-old detective: “I was old-school. In my heart I held women to what used to be called a higher standard. But the world had changed and if I wanted a relationship with the new order I had to at least be aware of its expectations.”

Over the course of his prolific career, Mosley has accumulated laurels including an O. Henry Award, a Grammy and a lifetime-achievement medal from the National Book Foundation. In my local bookstore, his novels are shelved in the mystery section. What distinguishes these works from certain crime-centric tomes on the literature shelves, such as “Motherless Brooklyn,” “The Goldfinch” or — while we’re at it — “The Brothers Karamazov”? In interviews, Mosley has objected to the label of “mystery writer.” Chandler, who also bristled at the pigeonholing of his oeuvre, insisted that “when a book, any sort of book, reaches a certain intensity of artistic performance it becomes literature.”

I like this blatantly subjective standard, and my nose tells me that Chandler often met it. As for “Every Man a King,” it’s a sterling example of a genre that it scarcely transcends. Of course, only a snob would always prize artistic performance over wisdom and fun. Mosley is an avid consumer of both poetry and comic books. When it comes to questions of what’s mystery and what’s literature, what’s tired and what’s timeless, and what’s highbrow or low, he seems to possess all the detachment of a Taoist sage. “Trying to set yourself up for importance and legacy … who cares?” he told The Paris Review.

Mosley imbues his memorable protagonist with a corresponding equanimity. When Aja-Denise castigates Joe for taking on Quiller’s case, he is at once pained by his daughter’s judgment and proud of her principles. “If someone had asked me at that moment to explain my emotional state,” Joe says, “I would have said, Everything good and everything bad that makes me human.”

Daniel Nieh is a translator and a novelist. His most recent book is “Take No Names.”

Spread the word