On August 25, the Central Intelligence Agency quietly posted on its website two documents on the military coup in Chile that had been kept top secret for half a century: the President’s Daily Brief (PDB) for the morning of the September 11, 1973—the day of the coup—and for September 8, 1973, as the Chilean military finalized its plans to overthrow the democratically elected government of Socialist Salvador Allende. The newly released documents proved almost impossible to find and read on the CIA website, buried among dozens of other previously declassified PDBs. Eventually, the State Department sent out a press advisory providing the links. The release of the PDBs was “in accordance with our commitment to increased transparency,” according to the press release. “We remain committed to working with our Chilean partners to try and identify additional sources of information to increase our awareness of impactful events throughout our shared history.”

Censored History

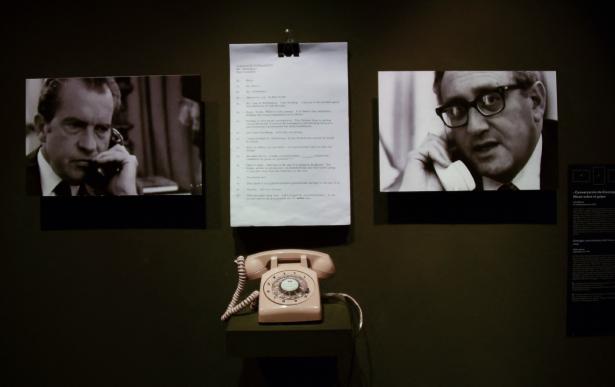

Among the documents on President Nixon’s desk on the morning of September 11, 1973, was the PDB—a daily CIA intelligence summary that contained three paragraphs on the opening salvos of the military coup in Chile. Fifty years after Nixon read it, we finally know what it says—very little. The intelligence provided to the president on the initiation of the coup was equivocal and erroneous. “Although military officers are increasingly determined to restore political and economic order, they may still lack an effectively coordinated plan that could capitalize on the widespread civilian opposition,” the PDB advised, incorrectly. “President Allende, for his part,” the PDB stated more accurately, “still hopes that temporizing will fend off a showdown.”

But Nixon had access to far more detailed and dramatic intelligence. A special CIA “CRITIC”—Critical Advance Intelligence Cable—that would have been distributed on an urgent basis to the highest levels of the White House on September 10, provided concrete reporting on the date, time, and place of the planned coup; another top secret CIA memo that reached the White House the morning of September 11 contained an urgent request from “a key officer in the military group planning overthrow President Allende” who asked “if the U.S. Government would come to the aid of the Chilean military if the situation became difficult.” How the president of the United States responded to that request is one of the details of the history of the coup that remain unknown.

Those dramatic CIA documents are among the thousands of secret records on Chile that have already been declassified. Indeed, Chile is one of the best-documented cases of covert US intervention for regime change. After Pinochet’s arrest in London in 1998 for human rights violations, hundreds of CIA operational records were finally released under a special “Chile Declassification Project” mandated by President Bill Clinton—along with approximately 24,000 other White House, NSC, FBI, and State Department records on the US role in Chile between 1970 and 1990. In 2016 President Obama ordered a special release of top-secret documents related to General Pinochet’s role as the mastermind of the act of terrorism that killed former Chilean ambassador Orlando Letelier and his young colleague Ronni Karpen Moffitt in Washington, D.C., in September 1976.

And yet, half a century later, there are still highly classified records that the US government continues to safeguard that would reveal critical details on what it did in, and what it knew about, Chile.

Third-Country Covert Collaboration

Among those secrets is how the CIA approached the Australian intelligence service, the ASIS, in late 1970 and asked for covert support in Santiago to help manage its Chilean agents. The CIA has not declassified a single document on this unique clandestine collaboration; we only know about it from the efforts of a tenacious Australian professor named Clinton Fernandes who, several years ago, filed a transparency lawsuit against the ASIS in Canberra. His legal petition resulted in the release of administrative records—documents on the more mundane side of setting up an espionage “station” in Santiago, such as rental agreements and the purchase of office equipment and vehicles for two agents. Both the CIA and the ASIS continue to hide operational records that include numerous intelligence reports from the Australian covert operatives to their CIA counterparts on meetings with Chilean assets embedded within the armed forces, the newspaper El Mercurio—a recipient of CIA funding—and the Christian Democratic party, among other key CIA-connected organizations in Chile.

Similarly, the United States government continues to withhold records on Brazil’s pivotal role in undermining the Allende government and abetting the installation of the Pinochet regime—the subject of a new book, El Brasil de Pinochet, by Brazilian reporter Roberto Simon. After Allende’s inauguration, President Nixon specifically ordered a secret approach to the Brazilian military regime for support of US efforts to undermine the Popular Unity government. No US documents have been released on those early communications; but one revealing memorandum of a December 1971 Oval Office meeting between Nixon and Brazilian military leader Gen. Emílio Garrastazu Médici indicates that a certain degree of collaboration may have developed.

During the meeting, Médici told Nixon that Allende would be overthrown “for very much the same reasons that Goulart had been overthrown in Brazil,” and “made it clear that Brazil was working towards this end,” according to a declassified summary of the meeting. Nixon responded “that it was very important that Brazil and the United States work closely in this field” and offered “discreet aid” and money for Brazilian operations against the Allende government. The two leaders agreed to set up a secret back channel for communications on the anti-Allende operations, but if that channel was ever used, neither the US nor Brazilian governments have released the messages that passed through it.

Brazil became the very first nation to officially recognize the military junta in Chile—a diplomatic orchestration coordinated with the Nixon administration, which wanted to avoid immediately embracing the new regime it had secretly helped to power. But Washington soon turned on the spigot of US economic, military, and political assistance, some of which was covert, to help Pinochet consolidate his violent rule. The CIA, for example, secretly financed a special delegation of Christian Democrats to tour Europe to publicly justify the coup to the international community. The US documents on this small but important post-coup propaganda operation remain highly classified.

CIA and DINA

Nor have a multitude of secret files on the CIA’s covert assistance to the development of the Chilean intelligence agency DINA into the repressive apparatus it became ever been released. In February 1974, Nixon and Kissinger dispatched a special emissary, CIA Deputy Director Vernon Walters, to meet secretly with Pinochet in Santiago and convey “our friendship and support” as well as “our wish to be helpful in a discreet way.” According to a secret report to Kissinger on their conversation, Pinochet directly asked Walters and the CIA to assist DINA’s “formative period” and identified Col. Manuel Contreras as “his key man.” “I told him that we would be glad to have Contreras or anyone else come up to see us,” Walters informed Kissinger, “to see what we could do to be of assistance to them.”

Yet the CIA files on Contreras’s first visit to Langley headquarters in 1974 and what the CIA agreed to do to assist the organizational formation and operations of DINA remain locked in agency vaults. Nor has the CIA ever declassified a single page of the personnel file it opened on Contreras in mid-1975, when high-ranking CIA officials decided to actually put the DINA chieftain on the covert payroll as an informant/collaborator. The intelligence information and collaboration Contreras provided to the CIA remains top secret. So, too, do the memorandums on the internal pushback inside the agency against putting Latin America’s most notorious torturer on the secret US payroll. Those still-classified arguments prevailed; after only a couple of months, the CIA station chief in Santiago informed Contreras that he was, essentially, fired! The classified records on this dramatic episode would be extraordinarily revealing, for Chileans and US citizens alike.

Contreras and the DINA were the driving force behind the creation of Operation Condor—a transnational effort by the military regimes in Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil, among others, to coordinate efforts to track down and eliminate civilian and militant opposition. Because foreign intelligence services were involved, the CIA has withheld key historical records including those relating to how it learned of Condor, and what actions it took in response to death squad missions undertaken by the Condor secret police agencies. What steps the CIA took in the aftermath of Condor’s most infamous terrorist operation—the September 21, 1976, car-bombing in Washington, D.C., that took the lives of Letelier and Moffitt—also remain shrouded in secrecy.

To its credit, on the 40th anniversary of the Letelier-Moffitt assassination in September 2016, the CIA finally declassified a comprehensive review, done in 1987, of its early intelligence on the case, which cited “convincing evidence that President Pinochet personally ordered his intelligence chief to carry out the murder[s].” But most of the raw intelligence records that assessment is based on remain secret 47 years later. Perhaps more importantly, the evidentiary files of a major Department of Justice investigation, conducted during the last year of the Clinton administration, identifying Pinochet as the intellectual author of an act of international terrorism in Washington, D.C., also remain off-limits to public scrutiny. Those files include more than 40 depositions taken in Chile from Pinochet henchmen, as well as a draft indictment that summarizes the evidence of his role as a mastermind of international terrorism. This documentation is not only relevant in Chile, where the ultra right continues its attempts to whitewash Pinochet’s criminality; it could contribute to the efforts of our country and others to protect themselves from future threats of state-sponsored international terrorism.

Finally, there is the matter of Pinochet’s personal corruption. A special Senate investigation into “Money Laundering and Foreign Corruption” in 2005 identified financial records that revealed over 100 offshore bank accounts, created with false Pinochet passports under such names as Augusto Ugarte and Jose Ramon Ugarte, among other fabricated identities, to hide over $28 million in ill-gotten funds. The evidence of illicit gains is already overwhelming. But the US Commerce Department continues to withhold even more banking records that could remind Chileans, and the world, of the corruption that accompanied Pinochet’s repressive dictatorship.

The Verdict of History

The declassification of US files “promotes the search for truth and reinforces our nations’ commitment to democratic values,” Chilean Foreign Ministry official Gloria de la Fuente stated in thanking the Biden administration for its efforts to respond to Chile’s request for documents. Indeed, at a time when prominent and powerful Chileans continue to insist that Pinochet was “a statesman” and to deny the realities of his barbaric regime, these documents have an immediate role to play in the divisive ongoing debate over the legacy of the coup and its meaning for Chile’s modern society—in the present and the future. As Chile evaluates its past on this powerful 50th anniversary, its citizens have a right to a full accounting—and the accountability that an airing of this dark history can bring. Not only should the United States commit to releasing its remaining records, but so too should the Brazilians, the Australians, and the other countries who played a role in Chile’s violent past.

But Chileans are not the only constituency for this important history. At a time when numerous nations, including the United States, are confronting the dire threat posed by authoritarianism to the survival of democratic institutions, access to the complete historical record on what happened in Chile remains critical to us all.

Copyright c 2023 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission. Distributed by PARS International Corp.

Peter Kornbluh, a longtime contributor to The Nation on Cuba, is co-author, with William M. LeoGrande, of Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana. Kornbluh is also the author of The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability.

Please support progressive journalism. Get a digital subscription to The Nation for just $24.95!

The Nation Founded by abolitionists in 1865, The Nation has chronicled the breadth and depth of political and cultural life, from the debut of the telegraph to the rise of Twitter, serving as a critical, independent, and progressive voice in American journalism.

Spread the word