“That’s the problem with Black Lives Matter! We need a strong leader like Martin Luther King!” Tyriq shouted as I wrote King’s name on the board.

I started my unit on the Civil Rights Movement by asking my high school students to list every person or organization they knew was involved. They replied with several familiar names: Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Emmett Till. Occasionally a student knew an organization: the NAACP or the Black Panther Party.

“Has anyone ever heard of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee?” I asked while writing the acronym on the board.

“S-N-C-C?” students sounded out as my black expo marker moved across the whiteboard.

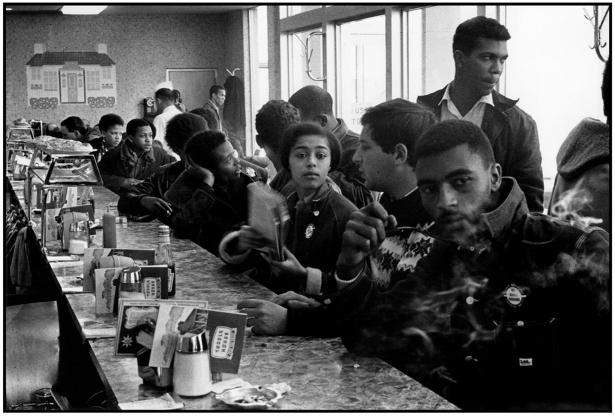

“Have you ever heard of the sit-ins?” I prodded.

“Yeah, weren’t they in Alabama?” Matt answered.

“No, Mississippi! Four students sat down at a lunch counter, right?” Kadiatou proudly declared.

This is usually the extent of my students’ prior knowledge of SNCC, one of the organizations most responsible for pushing the Civil Rights Movement forward. Without the history of SNCC at their disposal, students think of the Civil Rights Movement as one that was dominated by charismatic leaders and not one that involved thousands of young people like themselves. Learning the history of how young students risked their lives to build a multigenerational movement against racism and for political and economic power allows students to draw new conclusions about the lessons of the Civil Rights Movement and how to apply them to today.

You Are Members of SNCC

Pedagogically based on Rethinking Schools editor Bill Bigelow’s abolitionist role play, and drawing content from the voices of SNCC veterans and the scholarship of Howard Zinn, Clayborne Carson, and other historians, I created a series of role plays where students imagined themselves as SNCC members. In their roles, students debated key questions the organization faced while battling Jim Crow. My hope was that by role-playing the moments in SNCC’s history where activists made important decisions, students would gain a deeper understanding of how the movement evolved, what difficulties it faced, and most importantly, an understanding that social movements involve ordinary people taking action, but also discussing and debating a way forward.

I taught the role play in my U.S. history class at Madison High School in Portland, Oregon, and more recently in a course about the Civil Rights Movement at Harvest Collegiate High School in New York City. Both schools serve a diverse mix of Black, Latina/o, Asian, and white students — unusual examples of diversity for both public school districts. They also house a large population of students who come from low-income families.

To introduce the role play, I created a handout that situates students in the role of an SNCC member through providing background on what led up to the formation of SNCC. Before reading the handout out loud as a class, I told students they would be writing from the role of an SNCC member and should highlight any information — particularly about historical events — they might want to include. The role begins with historical background:

In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Boynton v. Virginia, and several other court cases, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled Jim Crow segregation unconstitutional. But from movie theaters to swimming pools, parks to restaurants, buses to schools, almost every aspect of public life in the South remains segregated.

In 1955, 50,000 African Americans in Montgomery (Alabama’s second-largest city) participated in a boycott to end segregation of the city buses. . . . But after the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the movement struggled to move forward. Segregationists launched a massive campaign of terror that prevented further gains. . . . While the protests of the 1950s gave you a sense of pride and power, it increasingly became clear that larger, more dramatic actions would be necessary to break the back of Jim Crow. You were prepared to act and you were not alone.

The handout continues by discussing the initial sit-ins that spread quickly across the South and led to the formation of SNCC. After reading about the sit-ins and SNCC’s founding conference in April of 1960, we quickly moved on to another crucial event that shaped SNCC’s early history: the Freedom Rides.

Freedom Rider Letter

To introduce the Freedom Rides, I edited together two clips from the PBS documentary Freedom Riders. The first part introduces students to the concept of the Freedom Rides, a series of bus trips organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) though the South to protest segregation in interstate travel facilities. The clip also takes students through the burning of one Greyhound bus in Anniston, Alabama, and the attack on the Freedom Riders in a second bus by a white mob in Birmingham.

The second part reveals that after the violence in Birmingham, the first round of Freedom Riders decided to fly to New Orleans and head home. It then turns to the Nashville students in SNCC who decided they couldn’t let the Freedom Rides end in failure. As SNCC leader Diane Nash explains in the video:

If we allowed the Freedom Ride to stop at that point, just after so much violence had been inflicted, the message would have been sent that all you have to do to stop a nonviolent campaign is inflict massive violence. It was critical that the Freedom Ride not stop, and that it be continued immediately.

After the clip, I tell students that to get in the role of an SNCC member, they will be writing letters to their parents as if they were planning to join the Freedom Rides. Together we read a short assignment that reiterates some of the basic facts about the Freedom Rides and gives them more information about what to write: “Describe for your parents the experiences that led you to risk your life in order to end segregation in the South. You can choose your gender, your race, your age, your social class, and the region where you grew up. Give yourself a name and a history. Be imaginative. In vivid detail, tell the story of the events that made you who you are now: a Freedom Rider.” While in reality, many Freedom Riders chose not to tell their parents, this activity allows students to think through what makes someone willing to take great risks for a just cause.

Whether giving this assignment as homework or giving students in-class time to work on it, I often get back incredible letters. Marquandre wrote passionately about why he felt the need to join:

Dear Mom and Dad,

I have made the decision to join the Freedom Riders. I know it’s a big risk, but I feel I need to do this. I’m sure you’ve heard about the bus that was burned in Anniston and the attack on the Freedom Riders in Birmingham. We can’t let this violence be the end. We need to show them that their violence can’t stop our fight.

Now I know you’ll be angry with me for dropping out of school to join the Freedom Rides. I really appreciate all you have done for me, and how hard you worked to get me to college. But seeing you work so hard for so little is why I’m doing this. I remember how you worked 10 or 12 hours a day just to pay the bills and put food on the table for me and my sisters.

I know you wanted a better future for me. But I’ve heard that nearly all of last year’s graduates fell short of their dreams to be doctors, lawyers, journalists, and so on. They say “knowledge is power,” but what’s the point of an education when I’m still going to end up in a low-wage job because I’m Black? I want Lily and Diana to know that their brother fought for their future. I want my children to grow up in a country where segregation doesn’t exist. . . . If not now, when? This is our time.

After students finished working, I had them read their letters to each other in pairs or small groups. Sometimes I asked the class to form a circle and read each letter aloud one by one. I was never disappointed when I took the time to do this. It helps students gain a deeper connection to their roles and creates a rich aural portrait of a social movement.

Organizing Mississippi

When students finished sharing their letters, we watched the movie Freedom Song. Freedom Song is an indispensable film that gives a gripping narrative based on SNCC’s first voter registration project in McComb, Mississippi. I’ve found that the film helps give students a deep visual understanding of SNCC’s organizing efforts that grounds the role play that follows. While watching Freedom Song, I asked students to pay attention to what leadership looks like in SNCC and how SNCC makes decisions. I also point out that in the last scenes of the film, some of the students from the local community where SNCC was organizing join SNCC and move to organize other parts of the state, while others stay behind and maintain the voter registration classes that SNCC began. In other words, as the best organizers do, SNCC organized themselves out of a job — they built a local movement that not only could sustain itself once they left, but could also help spread the movement to other parts of the state.

Next I distributed a handout containing three key questions that SNCC debated during their fight for racial justice in Mississippi:

1. Should SNCC focus its efforts on voter registration or direct action?

2. Should SNCC bring a thousand mostly white volunteers to Mississippi? If so, should SNCC limit the role of white volunteers?

3. Should SNCC workers carry guns? If not, should SNCC allow or seek out local people to defend its organizers with guns?

Each question is accompanied with some historical context that helps students understand why this has become a debated question within SNCC, as well as short arguments for both sides. Here’s an example from the handout:

Situation: While SNCC has always been a Black-led, majority-Black organization, there has always been a small number of white SNCC members. But Northern white students have been increasingly getting involved. At SNCC’s 1963 conference, one-third of the participants were white. Some staff members are now proposing to bring 1,000 mostly white students from all around the United States to Mississippi in the summer of 1964 to help with voter registration efforts. This plan has sparked discussion in SNCC on the role of whites in the movement.

Question: Should SNCC bring 1,000 mostly white volunteers to Mississippi? If so, should SNCC limit the role of white volunteers?

Arguments: Some Black SNCC members are concerned that instead of Black volunteers helping to build local leadership to organize their own communities, whites tend to take over leadership roles in the movement, preventing Southern Blacks from getting the support they need to lead. Many Northern whites enter SNCC with skills and an education that allow them to dominate discussions. If SNCC does decide to bring down white volunteers, these organizers insist that white activists should focus on organizing the Southern white community. After all, isn’t it the racism in white communities that is the biggest barrier to Black progress? Other SNCC members argue that too many local activists have been murdered for trying to organize and vote and the majority of the nation will only care when their white sons and daughters are in harm’s way. Bringing student volunteers from all around the country will mean increased attention on Mississippi’s racist practices from the family and friends of the volunteers, as well as the media. This spotlight might force the federal government to protect civil rights workers and Blacks in Mississippi trying to register to vote. In addition, some local organizers argue that if we’re trying to break down the barrier of segregation, we can’t segregate ourselves. Moreover, Black people are a minority in the United States and can’t change things alone.

I gave students the handout the class period before the actual role play and asked them to jot down initial answers to each question for homework. This is especially helpful for students who don’t feel as comfortable speaking in class discussion or who take longer to process their thoughts.

I explained to students that we would run our meetings in the same manner that SNCC ran meetings. We would choose a chair to call on other students and try to reach informal consensus. I echoed what I was told by SNCC veteran Judy Richardson: “Each one of us is putting our lives on the line, so we want to try to make sure that we come to a decision that we all feel comfortable with.” Once we chose a facilitator (or one for each question), I concluded with another insight I learned from Richardson: “Now the last thing you need to know about how SNCC ran meetings is that if things got really heated, someone would start singing and then others would just join in to remind everyone what they meant to each other and all they’d been through together. So, I’m going to teach you a song that they might have sung, and if our discussion at any point gets really contentious, we can sing to remind us that we are all in this together.” I sang for students “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around,” and encouraged them to sing with me the second and third round. This was a little out of my comfort zone as a teacher, and singing in a social studies class can be out of students’ comfort zone, but it became an essential and beautiful part of the role play. In addition to when the debate got heated, we sang the song to refocus after a lockdown drill, and I even heard a few students singing it in the hallways after class.

Students Run Their Own Meeting

To start the role play students sat in a circle. I encouraged them to read the entire question out loud — including the situation and the arguments — before jumping into each debate. This way, students who weren’t present when I gave out the questions or who didn’t have a chance to read them for homework could still participate in the discussions. Students ran the debate, though occasionally I did jump in to the discussion to play devil’s advocate, ensure they were taking all sides seriously, or re-emphasize the historical context that had provoked the question they were debating. When I did jump in, I always did so as an equal — raising my hand and waiting to be called on by the student facilitator. In general, I’ve been blown away by the seriousness and passion students bring to these discussions. Here’s a sample from our class debate on the first question: Should SNCC focus its efforts on voter registration or direct action?

Dwell: I think we should focus on voter registration because if we had some sort of political power we could take out the racist politicians.

Jade: I disagree. I think direct action is more useful. We’ve seen that the Brown v. Board decision didn’t actually desegregate schools. It took direct action. Action moves things forward faster and we want change now.

Giorgio: I agree with Dwell, focusing on voter registration is going to create a permanent change that will come from the government, not just changes in a few small places.

Rachel: But at the end of the day, it was the protests that pushed the government to make new laws. And isn’t it suspicious that the Kennedys are saying they will help us secure funds if we focus on voter registration? Whose side are they on? Do they just want these new voters to vote for them?

Shona: I see voter registration as direct action. As we saw in Freedom Song, SNCC members get beaten up whether they are doing sit-ins or voter registration. Both are forms of nonviolent disobedience. Why can’t we focus on both?

The time frame for the debates has varied depending on the pacing of class discussions and how much wiggle room I had built into the unit, but it has always taken at least one or two class periods. As we go, I have students jot down the decisions the class made, whether they agreed or disagreed with those decisions, and why.

When students finished debating the last question, I gave them a short reading adapted from several sources that explains how these debates played out in reality. Naturally, after debating the questions themselves, students were eager to know “what really happened.” Either for homework or as a debrief in class, I asked students to compare the decisions we made in class with SNCC’s ultimate decisions on those topics, write about what decision they found most interesting or surprising, and think about how SNCC’s experience in Mississippi changed the organization. While most students tended to agree with the decisions SNCC made, debating these questions as a class allowed them to look at the decisions more critically and not see them as inevitable. Imari wrote: “While SNCC chose not to limit the role of white volunteers I disagree with this decision. In class we discussed how white college students would tend to dominate discussions and reinforce Southern Blacks’ sense of inferiority. While I agree with SNCC that they shouldn’t segregate Black and white SNCC members, I think they could have placed some limits on white volunteers.”

Adeola’s comments about how organizing in Mississippi transformed SNCC were particularly insightful: “I think SNCC members felt like they couldn’t be safe without being armed. They would get violently attacked by whites for trying to get the most basic things like the right to vote. They probably began to see nonviolence as more of a tactic than a policy.”

After debriefing the role play, we watched part of an Eyes on the Prize episode that covers Freedom Summer [season 1, episode 5, Mississippi: Is This America?], when more than 1,000 volunteers joined SNCC organizers to dramatically increase voter registration in Mississippi. We also learned how during the summer, activists form the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party at the Democratic National Convention of 1964. The organizing involved in creating the MFDP was tremendous, full of valuable lessons, and worth spending time on in the classroom. I’ve often used Teaching for Change’s phenomenal lesson “Sharecroppers Challenge U.S. Apartheid” to cover this complicated effort with students.

Case Studies in Organizing Alabama

After learning about Freedom Summer, we return to the role play. Students are again seated in a circle and run their own meeting. This time, however, I split the class into three circles — groups large enough to still have a diverse group of vocal peers and small enough that they could get through questions a bit quicker. Armed with background about SNCC’s work in Mississippi, I wanted to move student discussions away from SNCC’s internal and more philosophical debates and toward more concrete problem-solving that happens during an organizing campaign.

I chose two “case studies” that further draw out SNCC’s history and unique contributions to the Civil Rights Movement. The first case study looks at the famous 1965 voting rights campaign in Selma, Alabama, from the perspective of SNCC. Several of my students had seen the movie Selma, but even for them, looking at the campaign through the eyes of SNCC was a new experience. I started with a short reading that gave students background about SNCC’s long work in Selma and the new campaign launched by Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The reading explains the difference between the two organizations’ organizing methods: “SNCC projects emphasize the development of grassroots organizations headed by local people. SNCC organizers work, eat, and sleep in a community — for years, if necessary — and attempt to slowly develop a large local leadership that can carry on the struggle eventually without SNCC field staff. . . . The SCLC led local communities into nonviolent confrontations with segregationists and the brutal cops and state police who backed up Jim Crow laws. They hoped to bring national media attention to local struggles and force the federal government to intervene to support civil rights activists.”

I explained to students why I’ve put them in multiple circles, have each circle pick their own facilitator, and hand out five “problem-solving” questions SNCC faced during the Selma campaign. In their circles, students debate and decide on answers to the five questions. Some of the questions ask students to decide whether they should support the efforts of the SCLC, while others are more open-ended and require students to come up with creative solutions. Here’s a short excerpt from one student discussion on whether SNCC should support the 50-mile nonviolent march from Selma to Montgomery that will go through some of the most violent areas of Alabama:

Aris: No, no, no! First, it’s a 50-mile march! Then King’s going to take them through these violent racist places. And he’s nonviolent, so that means that if they want to snatch our people up, we’re gonna have to let them!

Nakiyah: But King brings a lot of publicity with him. You think they are going to attack us while the cameras are on us?

Aris: It’s a 50-mile march. The cameras can’t be on us all the time.

Elian: But the troopers just shot a protester, we have to respond in some way and we’re stronger if we respond with King.

After students finish debating the questions, we read what really happened in a short excerpt I adapted from Clayborne Carson’s In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Students often leave this case study a little frustrated with King’s actions in Selma — a stark difference to how students feel after watching the movie, Selma. Aris commented, “The first march he wasn’t there. The second march he’s there, but turns it around. What’s up with this guy?” In our debrief discussion, we return to the philosophical differences between SNCC and SCLC to answer this. I point out to students that at least in this instance, the SCLC’s strategy worked and the Voting Rights Act was introduced out of the crisis in Selma. But my student Francisco would not let SCLC off the hook: “But they came in after SNCC had been working in Selma for two years. So who’s to say SNCC’s strategy didn’t work?” The point of this case study is not to answer these questions for students — but to get them to grapple with different organizing models for social change.

The next day we started on the second case study, which takes students through the SNCC organizing campaign in Lowndes County, Alabama. The format is identical to the previous day’s, so students come ready to dive in. One question asks students how SNCC will respond to increasing white terror. Another question, set after the Voting Rights Act, asks students now that most official barriers to Blacks voting have come down, should people vote for the Democratic Party? Especially given that Alabama’s Democrats have a slogan that touts “white supremacy?”

In addition to the voting rights campaign in Lowndes, the debrief reading for this case study takes students through the birth of the original Black Panther Party, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), and their impressive showing in the 1966 elections. In less than two years, Lowndes County went from a place that had not one registered Black voter to a model of independent Black organization that others aimed to emulate across the country.

Why Learn SNCC?

Probably the most important part of SNCC’s legacy is not its nonviolent direct action tactics, but its base-building through community organizing. SNCC was influenced by the communities in which they organized, just as SNCC influenced them. The debates throughout SNCC’s various organizing campaigns reflect this relationship with the communities in which they organized. Playing out these debates in the classroom shows students that social movements aren’t only about protest — but also about tactics, strategy, and the ability to hold a debate and move forward together. Tracking SNCC’s ideological transformation can also help highlight how social movements can quickly radicalize, as what seemed impossible only a few years before is made possible through protest and organization.

Too often, the experience of SNCC is ignored when we teach the history of the Civil Rights Movement. Instead, the movement is often taught with a focus on prominent movement leaders. The “Rosa sat and Martin dreamed” narrative not only trivializes the role of these activists, it robs us of the deeper history of the Civil Rights Movement. It’s not enough for students to simply learn about the sit-ins or Freedom Rides. SNCC’s organizing campaigns need to be at the center of civil rights curriculum. In today’s racist world, students need to grasp that social change does not simply occur by finding the right tactic to implement — or waiting around for a strong leader to emerge — but through slow, patient organizing that empowers oppressed communities. This crucial lesson of the Civil Rights Movement will help us plot a course for our movements today — and may help students imagine playing a role in those movements. As my student Nakiyah wrote me in her final course evaluation, “Learning about SNCC was so interesting because SNCC was so effective. Knowing that the racism they experienced still exists in a similar but different way today made me want to make a change and gather my generation to fight.”

Resource

For Adam Sanchez’s SNCC handout and role play, go here: http://bit.ly/2ihBTwa

Illustrator: Danny Lyon (Magnum)

Spread the word