Cooking for the History Classroom

Though I usually prefer writing to cooking, my most famous dish is my potato latkes. Latkes are consumed by Ashkenazi Jews (those from eastern Europe) to celebrate Hanukah. Handed down on oil-stained paper copies from my mother, our family recipe has drawn rave reviews from friends and neighbors for as long as I’ve served them at Hanukah parties.

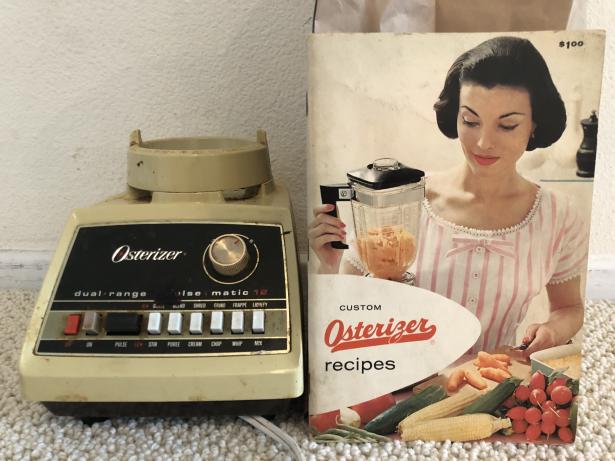

There is just one thing: the recipe was not created by my family, but by the Oster Manufacturing Company. In 1946, Oster introduced its Osterizer blender, urging American women to embrace this “modern day miracle.” According to the 1949 manual, the Osterizer promised to be a “veritable giant with a hundred ready hands to help turn your kitchen chores into more pleasant operations,” The blender came with a recipe booklet, to help women understand the “limitless uses” of their new appliance. By 1963, the Custom Osterizer Recipes booklet included a recipe for blender-made potato pancakes next to one for cheese blintzes, thus marketing to American Jewish customers alongside the majority Christian population cooking for holidays like Christmas and Easter.

My mother, Harriet Lipman Sepinwall, was an ideal customer for the Osterizer. The daughter of Jewish immigrants from Poland, she was eager to make both modern “American” and traditional Jewish meals for her and her new groom, Jerry Sepinwall, after their marriage in 1963. But she was also a first-generation college graduate and dedicated teacher who could not spend all day cooking. Harriet’s new Osterizer made cooking much easier for a working wife. My mother’s mother, Ida Lipman, had made latkes for Hanukah as she had learned in Poland, laboriously grating potatoes by hand. But for my mother, the Osterizer sped latke preparation. By the time Harriet and Jerry had three children, and my mother was professor of education at the College of Saint Elizabeth in New Jersey, the Osterizer latkes had become our family’s favorite holiday dish. When I grew up and began cooking for friends, I continued to use this recipe, with a few tweaks. Most importantly, I only purée half of the potatoes in the blender and use a food processor to grate the others, which makes the latkes crispier and more delicious.

I use this story with students at California State University, San Marcos, in my course History 383: Women and Jewish History to illustrate how a recipe’s history can illuminate lived experiences. My latke story provides a basis for our culminating project: a cookoff or “acculturation lab.” The course introduces many processes affecting Jews in global history, from expulsions and migrations to resistance, Jewish nationalisms, Jewish feminisms, and the Shoah. After a unit on American Jewish life, the students and I turn to historical cookbooks. Each student (alone or in pairs) selects one recipe to cook and explain in a poster. The students then vote on their favorite sweet dish and favorite poster. The project helps students learn more about Jews in diverse parts of the world (whether Turkey, India, or Argentina) through experiential learning.

As I tell students, learning about Jewish women just by reading texts would be particularly ahistorical. Jewish women typically were not able to sit and learn as their male counterparts would in a yeshiva or as we do in the modern university. Especially without time-saving modern appliances, much of women’s lives revolved around food preparation and childcare. Doing the cooking—seeing how long it takes and the labor involved—helps students better understand women’s daily lives in the past. Tasting the cooking—and noting similarities and differences between spices and flavors in Jewish recipes from different regions, as well as how they compare to non-Jewish foods from the same regions—helps them understand multiple historical processes. These include migration (for instance, of Spanish Jews to multiple parts of the Middle East after 1492) and acculturation, as Jews kept distinctive food traditions even while adapting recipes to local foodways (such as using avocados in kosher food in California).

The cookoff also helps me decenter Ashkenazi history. Many students think that all Jews come from Europe, but of course Jews have lived in many parts of the world, including India, Ethiopia, Morocco, and elsewhere. Tasting the deep variety of “Jewish” food, as cookbooks like Claudia Roden’s The Book of Jewish Food help us to do, reinforces class readings on the complexity of world Jewry. Indeed, the potato latkes that my family eats are not universally eaten by Jews for Hanukah; Mizrachi Jews (those from the Middle East and North Africa) make many other kinds of Hanukah dishes. For instance, one common Hanukah treat among Moroccan Jews is sfinge/svenj, a kind of fried donut.

The process of examining recipes and cooking instills concepts more deeply than traditional modes of assessment like quizzes or even papers. And it has a lasting impact—no one forgets the assignment, even after 20 years! For instance, Mel Fox Dhar, who graduated in 2004 and went on to work at Microsoft and Amazon, remembered that Jewish cookbooks helped mid-20th century Jewish women “maintain cultural connection as they moved out of big Jewish areas like New York City” into other parts of the country. Brenden Garvin, a 2019 graduate who now works as a corporate recruiter, recalled that “Learning about the culinary history of Jewish women . . . taught us how diverse Judaism is and [how] Jewish women lived their daily existence.”

The cookoff has also helped students better understand their own families as part of a larger history. Kristin Gazallo (class of 2019) experienced discrimination on campus as an Iraqi American. But in History 383, she was able to honor her family’s heritage by examining how Jewish Iraqi recipes compared to her family’s own cooking. It was especially meaningful to Kristin, who has since earned an MBA, to win our class cookoff with her kofta recipe only a few months after she had faced bigotry in the dorms. Similarly, Julia Friedman (2015 alumna and now writing an MA thesis on American Jewish women and feminism) remembers how exciting it was to pore over historic cookbooks and pick a turn-of-the-century dish to cook with her mother. She recalls that, even though their dish did not turn out well, “we really enjoyed connecting with each other in the kitchen, where we tried something new while discussing our family’s culinary history throughout the evening.”

For all these reasons, cooking (and eating) has an enduring place in my Women and Jewish History course. Students learn a great deal—plus the activity is delicious!

Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall is professor and director of graduate studies in history at California State University, San Marcos, and winner of the 2023 Wang Award for Outstanding Faculty Teaching from the CSU system. She tweets @DrSepinwall.

Spread the word