It’s over. On Wednesday, the House of Representatives approved, for a second time, the conference version of the Republican tax bill, clearing the way for Donald Trump to sign the legislation into law as soon as the relevant paperwork can be sent to the White House.

There was little drama even on Tuesday night, when the Senate took up the bill. With the few on-the-fence senators—such as Susan Collins, of Maine, who earlier this year was one of the Republican saviors of the Affordable Care Act—having expressed their support for the tax proposal, its passage was assured. Nonetheless, as members from both parties pointed out in speeches from the Senate floor, this was a momentous occasion.

Jeff Merkley, the liberal Democrat from Oregon, asked his Republican “friends” to consider what could have been achieved by spending a trillion dollars on fixing America’s infrastructure, or making health care more affordable, or improving the education system. “This is the biggest bank heist, not just in American history but in the history of the world,” Merkley declared.

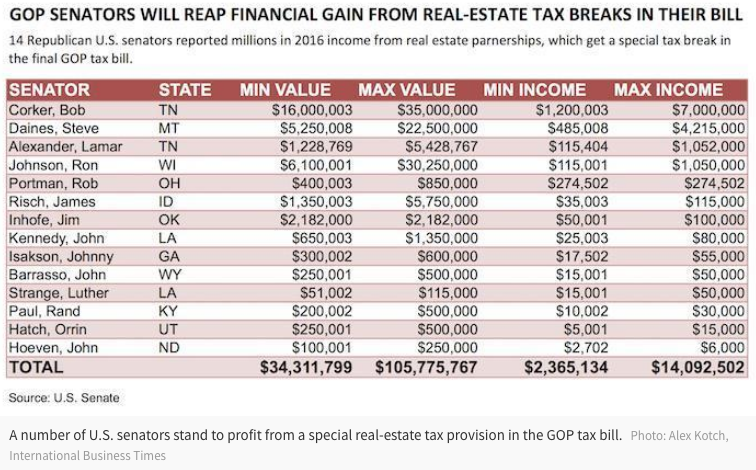

Evidently, the American public agrees with him. A new poll from NBC News and the Wall Street Journal shows that just twenty-four per cent of Americans believe that the Republican bill is a good idea, and sixty-three per cent of them believe that it was designed primarily to help corporations and the rich. A number of Republican senators contested this, of course. More than one of them complained about the “fog of disinformation” that the critics of the proposal had created. Rob Portman, of Ohio, insisted, “The burden of taxation actually increases in this bill for the wealthiest Americans.”

Portman didn’t say where he got this information, which was probably wise. It certainly didn’t come from the Joint Committee on Taxation, which is the official scorekeeper on Capitol Hill. In an analysis published on Monday, the Joint Committee said that households that earn between five hundred thousand and a million dollars a year would see their tax rates reduced, from 30.9 per cent to 27.8 per cent, on average. Households earning more than a million dollars a year would see their rates cut, from 32.5 per cent to 30.2 per cent. The independent Tax Policy Center, in its analysis of the final bill, said that next year, households in the top one per cent of the income distribution would receive tax reductions of $51,140, on average. And households in the top 0.1 per cent would see gains of $193,380.

Orrin Hatch, the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, did bring up the Joint Committee on Taxation’s analysis during his remarks. Indeed, he asked for it to be entered into the congressional record, saying that its “analysis shows that middle-income taxpayers are winners.” Regarding the immediate future, Hatch was right. The Joint Committee report shows that households that earn between fifty and seventy-five thousand dollars a year—roughly in the middle of the income distribution—would see their effective tax rate fall, from 14.8 per cent, this year, to 13.5 per cent, in 2019. According to the Tax Policy Center, households in the middle fifth of the income distribution would get an immediate tax cut of nine hundred and thirty dollars, on average.

But that’s only part of the story. Almost all the elements of the bill that benefit the middle class—reductions in personal tax rates, enlarged personal exemptions, and expanded child tax credits—are temporary measures. If they are allowed to expire, as the bill envisages, tax rates on middle-income people will go back up. By 2027, according to the Joint Committee’s report, households in the fifty-to-seventy-five-thousand-dollar income bracket will have seen their effective tax rate go back to 14.6 per cent. That is hardly different from what the rate is today.

As the night progressed, it was clear that the criticisms of the bill had rattled some Republican senators. Not content to quibble over the implications for individual family budgets, some of them resorted to outright fantasizing. “First, this is not a health-care bill,” Tim Scott, of South Carolina, declared. Further, Scott went on, “No one loses their insurance.” This was nonsense. The bill that Scott was voting for abolishes the individual mandate to purchase health insurance, a central element of the Affordable Care Act. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the mandate’s elimination will result in thirteen million fewer Americans being insured over ten years.

Arguably, Scott’s assertion was outdone by David Perdue, the former corporate executive who represents Georgia. “For the last eight years, America has suffered under big government bureaucrats’ vision of an America where the norm is two per cent economic growth,” Perdue said, before adding, “This is about getting the economy going so we can save Medicare and Medicaid.” Evidently, Perdue hasn’t spoken recently with House Speaker Paul Ryan, who, on Wednesday morning, gave an interview announcing that his party would now turn to “reforming” Medicare and Medicaid.

One of the most telling contributions to the Senate debate came from Tom Carper, a moderate, business-oriented Democrat from Delaware. He pointed out that it wasn’t Barack Obama, or any other Democrat, who invented the individual mandate. It originated in a 1993 health-care-reform bill that John Chafee*, a Republican senator from Rhode Island, put forward. It was subsequently picked up by another Republican, Mitt Romney, when Romney led the passage of a sweeping health-care law as the governor of Massachusetts. “It’s a Republican idea. It’s a market-based idea,” Carper said calmly.

But, of course, today’s Republican Party isn’t the Republican Party of Chafee or Romney. It’s the party of the Koch brothers, Sheldon Adelson, Robert Mercer, Heritage Action, the Club for Growth, alec, and the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. In many ways, this tax bill, with its huge breaks for major corporations and very wealthy individuals, is the logical corollary of the 2010 Citizens United Supreme Court ruling, which legitimized the wholesale corporate purchase of political parties and elected politicians.

The wealthy interests that bankroll the Republican Party have now achieved a major item on their agenda. What remains to be determined is whether this victory will help bring down the G.O.P. in next year’s midterm elections. In closing the Senate debate, Chuck Schumer, the Senate Minority Leader, predicted that it would; Republicans would “come to rue this day,” Schumer said. For the sake of American democracy, let’s hope that he is proved right.

[John Cassidy has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1995. He has written many articles for the magazine, on topics ranging from Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke to the Iraqi oil industry and the economics of Hollywood. He also writes a column for The New Yorker’s Web site. He is the author of “How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities” and “Dot.Con: The Greatest Story Ever Sold.” Cassidy is also a contributor to The New York Review of Booksand a financial commentator for the BBC. He came to The New Yorker after working for newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic. He joined the Sunday Times, in London, in 1986, and served as the paper’s Washington bureau chief for three years, and then as its business editor, from 1991 to 1993. From 1993 to 1995, he was at the New York Post, where he edited the Business section and then served as the deputy editor.]

Credit: Common Dreams

Spread the word