Why the Legacy of the Italian Communist Party Matters Today: The Difference Between the Swastika and the Hammer and Sickle

When I first moved to Italy I was twenty years old. I had taken a year off from College and moved to Urbino, to study at the University there. I wanted to become fluent in Italian and immerse myself in the culture. I had no idea that my junior year abroad would also have had such a profound impact on me, politically.

The birthplace of the painter Raphael, Urbino is a walled city, nestled among the hills of the Marche region. When the surrounding valley is blanketed in mist, it seems like a city floating among the clouds. The region was also one of Italy’s “Red Regions,” which included Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria and Le Marche. These were the regions where the Italian Communist Party (PCI) dominated local and regional elections between 1946 and the fall of the Berlin Wall.

At the time I was largely oblivious to this rich history. In hindsight this seems impossible, but perhaps it isn’t so surprising. While I would have described myself as an activist, it was firmly in the American liberal tradition of the word: you could fight hard for a better world but attempts to move beyond capitalism could only lead to one place: totalitarianism. Back then, I was active in the environmental movement and supported protecting civil liberties. I was supportive of the idea of unions, and aware of the anti-sweatshop movement, but I had no real connection to working class struggles or actual unions. I remember following the “Battle of Seattle” on the front page of Italy’s La Repubblica newspaper from my dorm room in Italy. The Italian press was sympathetic to the protesters. I had the sense that those in the streets were on the right side but had little understanding of what they were really fighting for. My junior year abroad was also ten years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. By then the successor to the PCI, the “Left Democrats” had replaced the hammer and sickle with the red rose and had more in common with Tony Blair than Enrico Berlinguer.

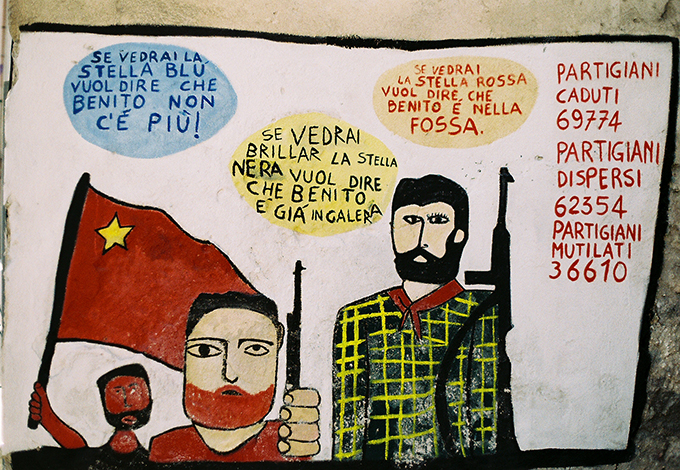

From the left, in the ovals: “If you see a blue star, it means Benito is gone. If you see a black star, it means Benito is in jail. If you see a red star, it means Benito is in the grave.” On the right are the number of dead, lost and injured partisans during the resistance. Murals found in the tiny town of Orgosolo in the isolated hinterland of Sardegna. Photo: Matt Hancock

Despite all of this, the PCI’s legacy left an indelible mark on me, affecting my political consciousness profoundly, if subconsciously as first. Perhaps it was because seeing the hammer and sickle on campaign posters was still commonplace at the time (the town council had been elected a few months before my arrival and the center-left coalition included the Communist Refoundation Party and the Italian Communist Party). Perhaps it was the way my friend described her vision of communism to me, describing what it would be like to raise children in a communist society. And no one identifying as a communist appeared to eat children.

I would only realize the impact my year in Urbino had on me politically as I was wrapping up my oral exam in contemporary European history. My professor asked me what the most important thing I had learned that year was. Though I had never reflected on this before, without even thinking I said: “that the hammer and sickle was not the same thing as the Swastika.”

Post-Soviet Rock in Red Bologna

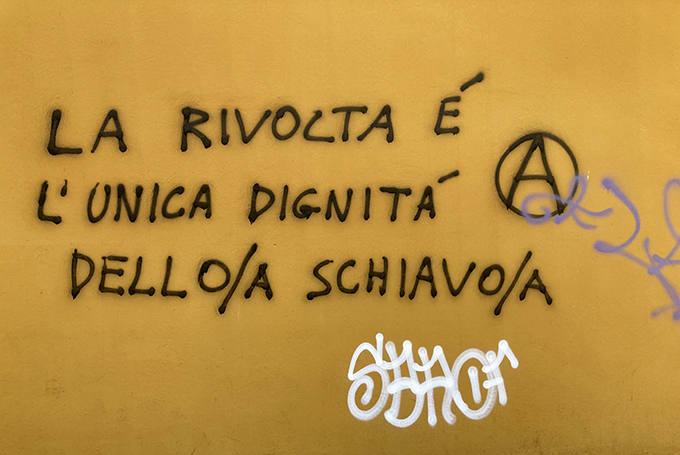

Graffiti in Bologna that says: “Rebellion is the slave’s only dignity.” Photo: Matt Hancock

I would return to live in Italy, this time in “Red Bologna,” in the summer of 2003, just in time for the national “Festa dell’Unita’.” Originally organized in 1945 by the PCI to finance “L’Unita” the influential party newspaper founded by Antonio Gramsci, the Festa was one of the few legacies of the PCI maintained by its successor, the Left Democrats. Imagine a state fair with some of the best cuisine in the world and the leading intellectuals of the mainstream left, plus great concerts with major recording artists and that’s sort of what the Festa is. That year or the year after, I would see performances by the group CSI (the former CCCP, a self-described Soviet-aligned Italian punk band) and sit in on interviews with Gore Vidal and the Polish Marxist Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman. In attendance were some of Italy’s most important center-left politicians.

This time, my politics were radically different from just three years earlier. This time I had returned to Italy specifically to learn about the PCI, the Italian way to socialism, and the role of the labor and cooperative movements in economic development in the red regions. By the time I returned, I had graduated college and had just come off two intense years in the student movement as a part of the group who founded Campus Greens, an offshoot of the Nader 2000 campaign. In 2001 we had organized the founding convention, in Chicago, brought together representatives from hundreds of college campuses around the US, and modified and approved the by-laws using a consensus method with at least 100 delegates. We capped off the convention with a super-rally, 32 days before 9/11, at the Congress Theater in Chicago, with speeches from, among others, Ralph Nader, Cornell West and Winona LaDuke. Patti Smith and Ani DiFranco brought their bands to the Rally as well.

I was later elected to Campus Greens’ National Steering Committee, then moved to Chicago permanently to take on the role of National Organizing Director. By the fall of 2002 the organization was being pulled apart by the politics of the student movement. In 2003 I took a part-time job at the Center for Labor and Community Research. Our offices were just down the hall from Carl Davidson, former Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) co-chair and “third wave” Marxist theoretician. In the few months I was there, I learned about the labor movement and the American Marxist tradition, and became interested in worker-self management and cooperatives as a viable model for socialism. When I told my boss I was moving to Bologna, Italy, he told me: great, go study Antonio Gramsci, the PCI, the labor and co-op movements.

By the time I attended my first Festa dell’Unita’ in August of 2003 in Bologna, I was a self-described communist, eager to learn about “actually existing socialism” through the experience of the PCI in Emilia-Romagna, and the left-aligned labor and cooperative movements. This radical shift in my thinking was only possible because of my experience, three years earlier in Urbino, helped me see past the liberal view that communism and fascism were just two sides of the same coin, inevitably leading to totalitarianism.

This time, I would spend nearly three years in Bologna, studying worker participation and industrial districts at the Institute for Labor (IPL) and learning about cooperatives while earning a Master’s in Cooperative Economics from the University of Bologna. Through interviews, research, and friendships, I came to know and appreciate the rich legacy of the PCI in Italy: a legacy that went far beyond the party’s stunning and sustained electoral success.

I would interview generations of rank-and-file union members and leaders, members and founders of cooperatives, leaders in the cooperative movement and elected officials. Most of the people I interviewed came from working class families or families of sharecroppers (an institution that persisted into the 1960s). Some came from professional families of modest means. Most of them began their political activism through the PCI, which, at different times, either exercised direct leadership, provided influence, managed conflict, or helped create consensus among the various institutions in the region. Most remained in the Party throughout their lives, even after its transformation. Some joined later, after experiences in the extreme parliamentary or extra-parliamentary left. Others had exited and then came back. Some were expelled (I remember interviewing a rank-and-file union member who proudly recounted being expelled in 1969, along with the rest of his comrades associated with the dissident newspaper Il Manifesto, which you can read in English here). In all cases, the PCI was a key reference point, a cultural influence, and a critical vehicle for working class people to collectively express their voice on a national stage, even in opposition to the Party.

While I wouldn’t find “actually existing socialism” in Emilia-Romagna, I did discover a cultural, political and economic legacy that was radically different from the reality I had grown up in: a legacy that had workers and farmers at its core, not simply as beneficiaries of social-democratic policies, but as agents in the development of a new society, economy and culture, led by a political party that, until its dissolution in 1991, remained rooted in the working class and committed to a socialist revolution. If the point of Communism was to put the working class and other marginalized social groups in the conditions to be the new ruling class, for the benefit of the majority, surely the example of Italy—especially in the Red Regions—is among the most important in our collective history.

Founding of the PCI

On January 15, 1921, the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) began its 17th Congress in the port city of Livorno. At the time of the 17th Congress, the Socialists were the single largest political party in Italy. The Congress came on the heels of the “Red Biennial,” a period of massive social unrest in the industrialized north (factory occupations, brutal confrontations between workers and the military in the streets of Turin) along with the flourishing of the working class movement and culture. It was in these years that the main labor federation in Italy was created, the left press flourished and workers, by the hundreds of thousands, joined the PSI. Observers, on the left and right, worried (or hoped) that after the October Revolution, Italy could be home to the next socialist revolution.

Inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution, Antonio Gramsci and Amedeo Bordiga attempted to convince a majority of PSI delegates in Livorno to adhere to the Third International’s 21 Conditions (among which were “unconditional support” for the soviet republics’ repression of counter-revolutionaries and removal from positions of power in the labor movement of leaders who didn’t support the 21 conditions). The debate at the congress was bitter. The Bolshevik faction, however, failed to convince enough delegates. Following the vote, they marched out of the 17th Congress, with a handful of delegates, founded the Partito Comunista d’Italia (PCdI) and voted to join the Third International. The Communists closed their convention singing L’Internationale while the Socialists concluded with the Worker’s Anthem.

Of course, the Red Biennial was followed by two years of fascist terrorism against unions, co-operatives, socialists, and communists. Fascist squads descended on towns governed by the Socialists and literally laid siege to them, with relative impunity. This violence culminated in the March on Rome in October 1922. Twenty days later, with just seven seats in parliament held by the Fascists, the King of Italy named Mussolini head of government. Preferring fascist terrorists to democratic socialists, Italy’s liberals and moderate rightwing groups joined forces with Mussolini’s fascists to create an electoral alliance that would win north of 60% of seats in parliament by 1924. And, as they say, the rest is history.

From Margin to Hegemony

The PCI presented its own candidates for parliament for the first time during the elections of 1921. That year the Communists won less than 5% of the vote, against the Socialists’ nearly 25%. In 1924 the PCI’s share of the vote dropped to under 4%. On November 6, 1926, all political parties except for the National Fascist Party were banned. Two days later Antonio Gramsci was arrested. He would die in prison nearly 11 years later. Gramsci’s words during his 1928 trial before the Special Fascist Court, would prove prophetic:

“I think… that all types of military dictatorship will, sooner or later, be upended by war. It seems evident to me, in that case, that it will be up to the proletariat to replace the ruling classes, taking over from them the reins of the country to lift up the fortunes of the nation… you will bring Italy to ruin, and it will be up to us Communists to save it.”

The PCI, because of its democratic centralist organizational model, support from Moscow and connection to the Third International, was the only Italian political party capable of operating clandestinely, which it do so until the liberation of Italy from Nazi occupation in 1945. This allowed the PCI to become the major force behind Italy’s armed resistance to Fascism, which began officially in 1943. Following liberation Italians flocked, by the millions to the PCI, which they saw as the legitimate heir to the October Revolution and the party of the anti-Fascist resistance. The PCI, along with the US-backed Christian Democrats, drafted the new anti-fascist constitution and began, quite literally, to rebuild Italian society. Because of the PCI, Italians were able to approve, via universal suffrage, one of Europe’s most progressive constitutions, recognizing Italy as a republic “founded on labor,” guaranteeing citizens work, healthcare, collective bargaining, formally declaring Italy’s “repudiation of war,” and guaranteeing asylum to citizens in other countries whose constitutions failed to guarantee the same rights as those guaranteed to Italians by theirs.

At the dawn of the new Italian Republic, the PCI emerged on the national and world stage as a revolutionary, mass political party, rooted in the tradition of the October Revolution, but with sights set on an Italian road to socialism: one that would be gradual, democratic and in coalition with a broad array of anti-Fascist social forces, led by the working class and farmers.

By 1946 the PCI counted 1.8 million members, a number that the Christian Democrats would not come close to until 1958. For the millions who joined the PCI during that time, the Party meant so much more than just electoral politics: the PCI taught millions of illiterate Italians how to read, and about political economy. This massive investment in education allowed the PCI to train and place a generation of sophisticated leaders, from the working class, in town councils, labor unions and associations, in parliament and the institutions of the state. Through the PCI millions of working class Italians participated in rebuilding and governing their society. Electorally, the PCI reached its peak in 1976, when it counted 1.81 million members, or just over 3 percent of the population of Italy. That year, the PCI won over 34% of the seats in both chambers of parliament, just behind the Christian Democrats. The party with the next highest percentage of votes that year were the socialists, with just under 10%.

And of course, in the Red Regions the PCI was second to none. Here, through municipal government and the party’s influence on the labor, cooperatives and small businesses, the PCI was the main force in rebuilding society and governing the development of one of the most important manufacturing regions in the world, built not on foreign direct investment and Taylorism, but by networks of small and medium businesses, many of which were also cooperatives, who, through a collaborative model, could match the technological sophistication and economies of scale of larger, vertically integrated foreign competitors. Through conflict and consensus, the PCI and its constellation of related institutions, ensured that economic development was also equitable and sustainable.

Even in those regions where the PCI was not the dominant political power, the Party would nonetheless have a profound impact on the lives of millions of workers and farmers throughout Italy. Through its network of offices and related social clubs, the PCI touched the lives of people in even the smallest, least developed and isolated towns. Deeply rooted in local communities and popular struggles, the PCI was a hub of social life for those identifying with the left and served as a leadership development school for the working class, an institution that helped millions achieve a sense of collective agency through participation in their local governments, unions, cooperatives, and community-based organizations. Through the PCI, working class people ascended to positions of power and influence throughout Italian society, including the institutions of the state and in parliament. Through a continual process of participation, debate and inclusion, millions of working class Italians would participate in, and have a direct impact on, the development of their communities and society.

End of an Era

On June 5, 1989, an unknown man blocked four tanks driving down an avenue in Beijing. Those tanks had just helped to clear pro-democracy protesters from Tiananmen Square. The day before the famous “tank man” picture was taken Poland held its first pluralistic elections since 1947, in which the dissident union Solidarity won 99 out of 100 seats in the Senate. That fall, on November 9, 1989 the German Democratic Republic (GDR) announced that East Germans could freely travel to West Germany. Three days later in Bologna, on a visit to the Bolognina neighborhood to commemorate an important battle of the Resistance, newly elected Party Secretary Achille Occhetto announced his openness to changing the name of the Italian Communist Party. That day, November 12, 1989, is now known as the “turning point,” or svolta. On December 22, 1989, the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin was opened. On June 13, 1990, the demolition of the Berlin Wall officially began and the two Germanies unified. Less than 18 months later, on December 9, 1991, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR voted to dissolve itself and the USSR.

The Italian Communist Party would not survive these epochal changes. Less than two months after the dissolution of the USSR, on January 31, 1991, the PCI held its final congress during which it decided to change its name to the Left Democratic Party, a victory for the centrist faction in the PCI. The Party’s left was split, with some remaining and others leaving to create the Communist Refoundation Party. The Left Democratic Party embraced neoliberalism and, for the first time since the PCI’s exclusion from government in 1948, former communists joined Italy’s governing coalitions, including two governments headed by former Communist Massimo d’Alema.

The current heir to the PCI is Italy’s Democratic Party (PD), a socially progressive, pro-EU, centrist formation in perpetual identity crisis. In 2013 former Florence mayor and paid Mohammed Bin Salman apologist, Matteo Renzi took over the Party. As Secretary and also Prime Minister, Renzi eliminated the Workers Bill of Rights (one of the most significant achievements of the Italian working class since passage of the Constitution) and led the Democrats to their worst electoral showing in their history, winning just 19% of the votes in 2018’s parliamentary elections.

To the left of the Democratic Party are Article 1 (as in Article One of the Constitution, “Italy is a Democratic Republic founded on Labor), Italian Left and Possible (which collectively, in coalition in the 2018 elections, received just 3.4% of the vote), Power to the People (1.1%) and the Communist Party (.33%). The Communist Refoundation Party, which at its height in 1996, commanded nearly 9% of the vote for Italy’s lower house, isn’t even a blip on the radar.

According to the most recent polling, if elections were held today in Italy, the Democrats would be the top vote getters, just barely edging out the post-fascist Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d’Italia). Despite this improvement over the Democrats’ performance in 2018, just 9 percent of working class voters support the Democrats. Almost 31% of working class voters surveyed would vote for the socially conservative, pro-business League (Lega), while nearly 20% would support the Brothers of Italy.

“As if Catholics were Presented with Incontrovertible Proof that God Didn’t Exist”

The PCI, until its voluntary dissolution in 1991, was a mass political party, deeply rooted in working class communities and struggles, and committed to a “third way” to socialism (not the neo-liberal “third way” of Tony Blair). Throughout its existence, the PCI neither surrendered to neo-liberalism nor remained in thrall to the October Revolution. Lucio Magri, expelled from the PCI in 1969 because of his leadership in the left Manifesto group and later re-admitted, serving in leadership positions, effectively and succinctly sums up the uniqueness of the PCI’s strategy and ideology:

“… the PCI represented… the most serious attempt… to open the road to a “third way:” to marry… partial reforms… broad social and political alliances, the faithful use of parliamentary democracy, along with bitter social struggles, with an explicit and shared critique of capitalist society; to build a mass party that was also deeply cohesive, militant, and rich in well trained cadres; affirming its membership in the global movement for revolutionary change, accepting the limits of such membership, but in relative autonomy… the unifying strategic idea was that the consolidation and evolution of ‘actually existing socialism’ did not constitute a model that, one day, could be applied in the West, but was the necessary historical background for the realization of another type of socialism that respected liberties.”

On the eve of its dissolution, the PCI was still Italy’s second most important political party. In the final parliamentary elections, the PCI would participate in, in 1987, the Party won 27% and 28% of the vote in the House and Senate, respectively. During the 1989 elections for the European parliament the PCI won 28% of the seats assigned to Italy. And in the year prior to its dissolution, the Party counted 1.26 million members. Still the PCI was not able to survive, in name or in substance, the end of actually existing socialism.

In December 1981, ten years before the PCI voted to dissolve itself, a Soviet-backed military junta seized power in Poland, declared martial law and violently repressed the dissident union Solidarity. Days later, in a public press conference, Party Secretary and one of Italy’s most beloved politicians, Enrico Berlinguer, would reflect on the events in Poland, the rise of the USSR and the significance of the October Revolution. Berlinguer described the October Revolution as “the most significant revolutionary event of our epoch,” an event which served as the “propulsive thrust” behind struggles and important victories in the movement for working class emancipation. For Berlinguer, however, the events in Poland signaled the end of the October Revolution’s propulsive thrust and the ability of the USSR to act as a progressive force for working class liberation.

A friend of mine, Benito Benati, (a PCI member and leader in the cooperative movement) described the impact of the collapse of the Soviet Union for Communists would be as if Christians were presented with incontrovertible proof that God did not exist: an event from which one could not recover. Perhaps this explains why the PCI, despite all of its victories, millions of members and place in Italian society, was so unprepared for the collapse of actually existing socialism, and unable to find its footing in a post-Soviet world in which capitalism seemed, at least temporarily, victorious.

The Propulsive Thrust of the PCI

After 16 years in the United States I returned to Bologna in January 2021, this time as an Italian citizen, where I now live with my two children and work with Italy’s largest, and historically left-aligned, labor confederation CGIL (Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro or the Italian General Confederation of Labor) and their Institute for Economic and Social Research in Emilia-Romagna, studying the impact of changes in technology and the economy on labor relations and workplace participation.

The current state of the electoral left here is, quite frankly, depressing. Despite 20 years of efforts, no credible anti-capitalist political party has emerged. And during that same timeframe, two generations of politicians have totally squandered the immense cultural patrimony of the PCI (I recently learned that the Democratic Party in Bologna, which after recent electoral disasters now promises to be “close to the people,” had closed the party’s workplace-based social circles).

Of course, the current state of electoral politics has multiple causes and reflects the transformation of the traditional working class as well as the crisis of elite consensus globally. In this sense, the dissolution of the PCI is both a cause and symptom of this more general crisis. With its dissolution into the Left Democratic Party, Italy lost its largest mass political party. The PCI was also independent, self-funded by individual member dues. As such, Italy’s labor and social movements lost their most important voice in parliament. The PCI also impacted popular participation in political life indirectly, if no less profoundly: as Lucio Magri because the PCI brought millions of citizens from Italy’s popular classes into politics in an organized fashion, it forced Italy’s other major parties to develop their own mass bases. Today, no such vehicle exists.

However, the legacy of the PCI, and the anti-Fascist resistance it led, are all around us today, in the labor, environmental and other contemporary social movements. These movements, even without effective political leadership like that provided by the PCI, involve millions of Italians in the fight against neo-liberalism, patriarchy, anti-LGBTQ+ and anti-immigrant discrimination, and environmental destruction. Here are just a few examples:

- A peculiar feature of the Italian economy is the presence of cooperative enterprises, more per capita here than anywhere else in the world. The bulk of the cooperative movement has historically been aligned with the Left (though Catholic-aligned cooperatives are a significant force as well). Since the 2008 financial crisis, Italians have turned increasingly to the cooperative model as both a means of resistance and of building an alternative. Since the crisis, workers together with their unions, the cooperative movement, supportive national legislation, local governments and a network of banks and cooperative investors have saved hundreds of bankrupt firms through conversion to worker-owned co-ops. Having been saved they are now thriving through conversion to worker-owned co-ops. As a signal of how important this model has become, the main labor federations and the cooperative movement recently developed a formal agreement to marshal resources and jointly support worker buyouts. Italians are also turning toward cooperatives as a way of explicitly moving beyond, or outright rejecting, traditional market relationships. The experience of “community cooperatives” creating a Green New Deal from below by redefining the role of citizens as producers, consumers and collective owners, is but one example. The emergence of the movement for food solidarity “Campi Aperti” (Common Fields), connected with Bologna’s squatter movement, unites farmers and consumers as “co-producers.” The related self-managed consumer co-op, Camilla (the first in Italy), seeks fair treatment of workers, a “just price” for producers and ecological sustainability through a model of “participatory certification” of producers. These new cooperatives are reclaiming a progressive role for the movement in Italian society, rooted in the resistance to Neo-liberalism and environmental degradation. Most compelling, the spirit that animates these new cooperatives harkens back the values of the 18th century workers’ mutual aid societies, from which the modern cooperative, labor and socialist movements were born.

- On March 22, 2021, as Amazon workers in Bessemer were turning in their NLRB ballots for union recognition, Italy’s main labor federations, led by CGIL, successfully pulled off a day-long strike, involving Amazon’s entire supply chain. The strike, which according to Italy’s financial paper Il Sole 24 Ore, involved 40,000 workers, halted deliveries throughout the peninsula that day. Though primarily designed to support the bargaining efforts of last-mile drivers, the strike would have an impact on Amazon employees as well. While the company contends that no more than 20% of workers struck, Amazon and its supply chain nonetheless felt compelled to return to the bargaining table, making important concessions to workers. Equally significant, shortly after the strike, workers in Amazon’s Piacenza “fulfillment center” elected a plant-based bargaining unit (Rappresentanza Sindacale Unitaria); the first bargaining unit recognized anywhere in the world in an Amazon workplace.

- About 200 kilometers southwest of Piacenza, in Campo Bisenzio just outside of Florence, workers at Driveline GKN, owned by British investment fund Melrose Financial, received an email on July 9, 2021, announcing the immediate closure of the plant. Workers there, represented primarily by CGIL’s metalworkers’ union, FIOM, and self-organized in the plant for a number of years as “The Collective,” decided to fight back by occupying the plant. The town’s mayor, a member of the Democratic Party, issued a local ordinance preventing trucks from entering or leaving the plant.

Meanwhile, through their collective, the GKN workers mobilized national support for their cause under the slogan “Rise Up” (Insorgiamo), harkening to their collective roots in the anti-Fascist resistance. On September 18, GKN workers organized a national rally in Florence to protest the proposed plant-closure, inviting others from throughout Italy, not just to come support their cause, but as a call to action to rise up and fight back against similar situations elsewhere. According to the press, 20,000 supporters showed up. Organizers put the number closer to 40,000. Protesters joined from all over Italy, and included other workers facing layoffs and plant closure, like the Whirlpool workers in Naples fighting the closure of their plant. Additional protests were members of Italy’s National Association of Partisans, students and environmentalists. FIOM, the union, succeeded in getting a court order to block the mass layoffs and the company is now at the bargaining table, along with the union and the national government. To support the workers, and reinforce the connection between their struggle and the struggle against Fascism, the mayor celebrated the 77th anniversary of Campo Bisenzio’s liberation from Nazi occupation in front of the GKN plant gates, saying “this is a defining moment: each one of us… has to say without mincing words who’s side are we on… the side of the workers, of the business as an instrument for improving the lives of people and the local community… or the side of profit, finance, speculation.”

Here you can watch a video of their anthem, Che Fatica Che Ti Chiedo, Oggi Devi Scioperare (What a Sacrifice I Ask of you, Today You Must Strike) with scenes from their movement of resistance.

- The workers at GKN are represented primarily by FIOM (Federazione Italiana di Operai Metalmeccanici or the Italian Federation of Italian Metalmechanical Workers), the militant metalworkers union federated under Italy’s largest labor federation, CGIL. CGIL, after Italy’s liberation allied with the PCI, has 5.5 million members, including pensioners, or just over 10% of the adult population in Italy. Because of Italy’s model of labor relations, nearly all workers in the economy are covered by a collective bargaining agreement. CGIL’s mission is to represent workers in all facets of their life. As such, CGIL’s work extends far beyond the bargaining table, to include advocating for higher quality, publicly funded healthcare, good schools, environmental issues, immigrant and women’s rights, environmental issues, and LGBTQ+ rights. After the recent failure of the “Zan” law, anti-discrimination legislation particularly focused on the LGBTQ+ community, the CGIL lamented the defeat with a press release that promised “… our Battle Continues.”

On Saturday September 9, 2021, during an anti-vax rally, protesters, led by known leaders of Italy’s neo-Fascist movement, broke into and ransacked CGIL’s national headquarters in Rome. The next day, all across Italy, thousands flocked to their local CGIL office to show support for the union.

The Camera del Lavoro (The Chamber of Labor – CGIL’s headquarters in Bologna) on October 10, 2021, the day after Fascists attacked, occupied, and ransacked CGIl’s main HQ in Rome. Photo: Matt Hancock

The following month, on October 16, 200,000 supporters, arriving by train, bus and car, poured into Italy’s capital in a peaceful show of anti-Fascist force, declaring “no more fascisms.” All three of Italy’s labor federations came together for the rally, as did leaders of every center-left political party, students, environmentalists and members of Italy’s National Association of Partisans. Maurizio Landini, CGIL’s top leader and former head of the militant FIOM union, explicitly and elegantly linked the anti-Fascist resistance to today’s social, labor and environmental movements. Participants concluded the rally by singing “Bella Ciao,” the partisan song and Italy’s unofficial national anthem.

Conclusion

In a paradox symptomatic of the current crisis of political representation, some of those workers who took to the streets that day to support CGIL are the same workers who, on election day, vote for Italy’s two rightwing, reactionary parties. I think this paradox, coupled with the strength and vibrancy of Italy’s labor and social movements, are also a testament to something else: that the propulsive thrust of the anti-fascist resistance and the legacy of the PCI has hardly exhausted itself among Italy’s popular classes. The real crisis is of political representation.

For activists searching for answers to what a 21st century political project for revolutionary change might look like, the history of Italy’s Communist Party offers critical insights as well as profound inspiration. For groups like the Democratic Socialists of America some of the questions that discovering the rich history of the PCI can help leaders grapple with are:

- Where would a truly majoritarian Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) derive its legitimacy, beyond the strength of its ideas or association with specific political campaigns? What “propulsive thrust” would be capable of sustaining a movement for democratic socialism over decades?

- How would a mass, revolutionary political party balance the need for vibrant internal democracy with the need to be able to speak with one voice on important issues?

- In a radically transformed, global capitalist economy, where the “proletariat” (in the theoretical sense Marx intended by the term) makes up a smaller and smaller percentage of the overall working class, what are the class forces that could be organized to resist and overcome capitalism?

- How does a revolutionary political force govern effectively under capitalism in ways that meet peoples’ needs now, while building support — and laying the groundwork — for a more radical rupture later?

- How would a mass movement for Democratic Socialism understand and confront the rise of reactionary movements?

- How would a movement for Democratic Socialism achieve cultural hegemony, an essential element in the long “war of position,” to borrow a term from Gramsci, against global capitalism?

- Finally, what would it look like for a majoritarian DSA movement to relate to the labor movement, and how would the DSA effectively train millions of working class people to participate, as leaders, in politics, society and the economy, radically opposed to capitalism and capable of self-government for the benefit of the majority?

Matt Hancock is an organization development consultant and researcher based in Bologna, Italy where he lives with his two children. His interests are in collaborative forms of work organization and worker power. Matt was a co-founder and former Organizing Director of Campus Greens as well as a co-founder of the Central Jersey Chapter of Democratic Socialists of America. Matt holds a BA in History from Skidmore College, a Masters in Cooperative Economics from the University of Bologna and is the author of "Compete to Cooperate" a short book on the cooperative movement of Imola, Italy.

Spread the word