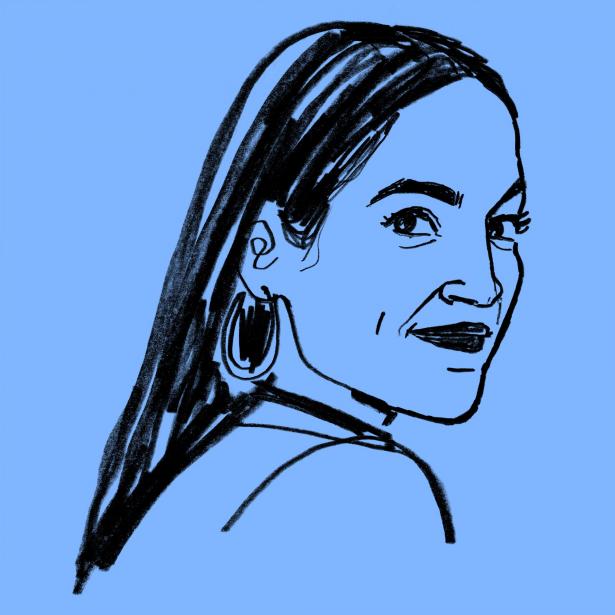

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a Democrat representing parts of Queens and the Bronx (including Rikers Island), quickly became the most prominent progressive voice in the House of Representatives after she defeated a twenty-year incumbent, Joe Crowley, and went to Capitol Hill in January, 2019. In Congress, she is hardly alone in her advocacy for issues ranging from Medicare for All to the Green New Deal; she belongs to the Bernie Sanders wing of the Party. But few in the history of the institution have so quickly become a focus of attention, admiration, and derision.

Elected when she was twenty-nine, the youngest woman ever to serve in the House, Ocasio-Cortez has proved herself an effective examiner in committee hearings and a master of social media. In other words, she offers both substance and flair, and this combination seems to drive her critics to the point of frenzied distraction. Fox News, the Post, and the Daily Mail, along with a collection of right-wing Republican foes in Congress, obsess over her left-wing politics and her celebrity. In November, Paul Gosar, a Republican representative from Arizona who has spoken up for white-nationalist leaders and voted against awarding the Congressional Gold Medal to police officers who defended the Capitol on January 6, 2021, posted an anime sequence that depicted him killing Ocasio-Cortez with a sword. More recently, a former Trump campaign adviser, Steve Cortes, went online to mock Ocasio-Cortez’s boyfriend, Riley Roberts, for his sandalled feet, prompting her to fire back, “If Republicans are mad they can’t date me they can just say that instead of projecting their frustrations onto my boyfriend’s feet. Ya creepy weirdos.”

When we spoke earlier this month, by Zoom, Ocasio-Cortez talked at length not only about the impasse the Democrats now face but also the general atmosphere of working in Congress. “Honestly, it is a shit show,” she said. “It’s scandalizing, every single day. What is surprising to me is how it never stops being scandalizing.”

The interview, which was prepared with assistance from Mengfei Chen and Steven Valentino, took place on February 1st, and has been edited for length and clarity.

Much of the Biden Administration’s agenda in Congress has pretty much stalled. A term that began with lofty F.D.R.-like ambitions is now at a standstill. How would you rate the President’s performance after a year?

There are some things that are outside of the President’s control, and there’s very little one can say about that, with Joe Manchin and [Kyrsten] Sinema. But I think there are some things within the President’s control, and his hesitancy around them has contributed to a situation that isn’t as optimal.

My concern is that we’re getting into analysis paralysis, and we don’t have much time. We should really not take this present political moment for granted, and do everything that we can. At the beginning of last year, many of us in the progressive wing—but not just the progressive wing—were saying we don’t want to repeat a lot of the hand-wringing that happened in 2010, when there was this very precious opportunity in the Senate for things to happen.

People in the Biden White House would argue that the margins are the margins and Manchin’s politics are what they are. He comes from a state that is dominated by a much more conservative vote. And Sinema is . . . unpredictable. They would argue that they made concession after concession and still got nowhere.

The Presidency is so much larger than just the votes in the legislature. This is something that we saw with President Obama. I think we’re seeing this dynamic perhaps extend a little bit into the Biden Administration, with a reluctance to use executive power. The President has not been using his executive power to the extent that some would say is necessary.

Where would you move first?

One of the single most impactful things President Biden can do is pursue student-loan cancellation. It’s entirely within his power. This really isn’t a conversation about providing relief to a small, niche group of people. It’s very much a keystone action politically. I think it’s a keystone action economically as well. And I can’t underscore how much the hesitancy of the Biden Administration to pursue student-loan cancellation has demoralized a very critical voting block that the President, the House, and the Senate need in order to have any chance at preserving any of our majority.

What is in the realm of the achievable, the realm of the possible, between now and the election?

That’s why I kind of started off by talking about the executive powers of the President, because I don’t think that there’s any guarantee of getting something through that Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema will approve of that will significantly and materially improve the lives of working people. It’s a bit of a dismal assessment, but I think that, given an analysis of their past behavior, it is a fair one. The President has a responsibility to look at the tools that he has.

You had some political experience before you were elected, but it was from some distance. You weren’t a member of Congress. You weren’t “in the room.” What do you see in the room? What is it like, day to day, being a member of this institution, which, I have to say, from outside, looks like a shit show?

Honestly, it is a shit show. It’s scandalizing, every single day. What is surprising to me is how it never stops being scandalizing. Some folks perhaps get used to it, or desensitized to the many different things that may be broken, but there is so much reliance on this idea that there are adults in the room, and, in some respect, there are. But sometimes to be in a room with some of the most powerful people in the country and see the ways that they make decisions—sometimes they’re just susceptible to groupthink, susceptible to self-delusion.

Sketch it out for us. What does it look like?

The infrastructure plan, if it does what it’s intended to do, politicians will take credit for it ten years from now, if we even have a democracy ten years from now. But the Build Back Better Act is the vast majority of Biden’s agenda. The infrastructure plan, as important as it is, is much smaller. So we were talking about pairing these two things together. The Progressive Caucus puts up a fight, and then somewhere around October there comes a critical juncture. The President is then under enormous pressure from the media. There’s this idea that the President can’t “get things done,” and that his Presidency is at risk. It’s what I find to be just a lot of sensationalism. However, the ramifications of that were being very deeply felt. And you have people running tough races, and it’s “he needs a win.” And so I’m sitting there in a group with some of the most powerful people in the country talking about how, if we pass the infrastructure bill right now, then this will be what the President can campaign on. The American people will give him credit for it. He can win his Presidency on it. If we don’t pass it now, then we’ve risked democracy itself.

Who’s in the room? You say the most powerful people.

You’re talking about everybody from leadership to folks who are in tough seats, but all elected officials in the Democratic Party on the federal level. And people really just talk themselves into thinking that passing the infrastructure plan on that day, in that week, is the most singular important decision of the Presidency, more than voting rights, more than the Build Back Better Act itself, which contains the vast majority of the President’s actual plan. You’re kind of sitting there in the room and watching people work themselves up into a decision. It’s a fascinating psychological moment that you’re watching unfold.

It’s not to say that all these things that they’re saying are a hundred-per-cent false. But I come from a community that is often discounted in many different ways, because, you know, these are “reliable Democrats.” Like, what she has to say doesn’t matter, etc. What does she know about this political moment? The thing that’s unfortunate, and what a lot of people have yet to recognize, is that the motivations and the sense of investment and faith in our democracy and governance from people in communities like mine also determine majorities. They also determine the outcomes of statewide races and Presidential races. And, when you have a gerrymandered House, when you have the Senate constructed the way that it is, when you have a Presidency that relies on the Electoral College in the fashion that it does, you’re in this room and you see that all of these people who are elected are truly representative of our current political system. And our current political system is designed to revolve around a very narrow band of people who are, over all, materially O.K. It does not revolve around the majority.

You’ve used a phrase “if we have a democracy ten years from now.” Do you think we won’t?

I think there’s a very real risk that we will not. What we risk is having a government that perhaps postures as a democracy, and may try to pretend that it is, but isn’t.

What’s going to bring us to that point? You hear talk now about our being on the brink of civil war—that’s the latest phrase in a series of books that have come out. What will happen to bring us to that degraded point?

Well, I think it has started, but it’s not beyond hope. We’re never beyond hope. But we’ve already seen the opening salvos of this, where you have a very targeted, specific attack on the right to vote across the United States, particularly in areas where Republican power is threatened by changing electorates and demographics. You have white-nationalist, reactionary politics starting to grow into a critical mass. What we have is the continued sophisticated takeover of our democratic systems in order to turn them into undemocratic systems, all in order to overturn results that a party in power may not like.

The concern is that we will look like what other nation?

I think we will look like ourselves. I think we will return to Jim Crow. I think that’s what we risk.

What’s the scenario for that?

You have it already happening in Texas, where Jim Crow-style disenfranchisement laws have already been proposed. You had members of the state legislature, just a few months ago, flee the state in order to prevent such voting laws from being passed. In Florida, where you had the entire state vote to allow people who were released from prison to be reënfranchised after they have served their debt to society, that’s essentially being replaced with poll taxes and intimidation at the polls. You have the complete erasure and attack on our own understanding of history, to replace teaching history with institutionalized propaganda from white-nationalist perspectives in our schools. This is what the scaffolding of Jim Crow was.

So there are many impulses to compare this to somewhere else. There are certainly plenty of comparisons to make—with the rise of fascism in post-World War One Germany. But you really don’t have to look much further than our own history, because what we have, I think, is a uniquely complex path that we have walked. And the question that we’re really facing is: Was the last fifty to sixty years after the Civil Rights Act just a mere flirtation that the United States had with a multiracial democracy that we will then decide was inconvenient for those in power? And we will revert to what we had before, which, by the way, wasn’t just Jim Crow but also the extraordinary economic oppression as well?

Do you think many Republicans share your concern about the fate of democracy? Do you have those kinds of conversations?

It’s a complex question because there’s so many different kinds of Republicans. But I’m reluctant to get into the navel-gazing of it, because, at the end of the day, they all make the same decisions. You might be able to appeal to the good natures or even a sense of charity of a handful, but ultimately we have what we have. At the end of the day, you know, who cares if they’re true believers or if they’re just complicit? They’re still voting to overturn the results of our election.

We’re constantly told, if you could only hear what’s being said in the cloakrooms, a lot of Republicans find Donald Trump repulsive but know that they’re going to lose their seats if they say so. Is being in Congress such a great job that you will trade your principles and soul for that job?

What I think some Republicans struggle with, the very few that are in that position, is a concern that they will be replaced by someone even worse. You know, O.K., externally I might look like a good soldier, I might look like I’m falling in line, but, if I lose my primary and I get replaced with ten more Marjorie Taylor Greenes, we’ll be in an even worse situation.

That’s perhaps where they may be coming from. And, to a certain extent, you do have these critical moments. You have January 6th, and, if Mike Pence had made a different split-second decision that day and done what President Trump was asking of him, we would be in a very different place right now.

When you are asked questions about whether or not Nancy Pelosi should stay as Speaker, when you’re asked questions about the rather advanced ages of Steny Hoyer, Jim Clyburn, and Chuck Schumer, does it make a difference? You’re saying it’s structural. It’s not generational.

It’s both. The reason we have this generational situation that we do is also, in part, due to our structures. The generational aspect of things is absolutely pertinent to the kind of decision-making. There is this world view, this appeal, of a time passed that I think sometimes guides decision-making. President Biden thought that he could talk with Manchin like an old pal and bring him along. And, frankly, that was what the White House’s strategy was, in terms of what they communicated to us. That’s how they tried to sell passage of not even half a loaf but a tenth of the loaf. It was “We promise we’ll be able to bring them along.” There is this idea that this is just a temporary thing and we’ll get back to that. But I grew up my entire life in this mess. There’s no nostalgia for a time when Washington worked in my life.

Is it healthy or not for the Democratic Party for Nancy Pelosi to remain in place as the Speaker, as leader of the Democratic caucus in the House?

It’s really all about a specific moment that we’re in. We are in such a delicate moment of the day-to-day, particularly with the threats to our democracy. I believe that, at the end of the day, there’s going to be a generational change in our leadership. That is just a simple fact. Now, when that particular moment happens? I think it’s a larger question of conditions and circumstance.

You don’t want to go near this one.

It’s a tough question. It’s not even just a question of the Speaker. It’s a question of our caucus. I wish the Democratic Party had more stones. I wish our party was capable of truly supporting bold leadership that can address root causes.

Is it that the representatives don’t have the stones, or do you want a different public opinion, as it were? In other words, for example, take “defund the police” as a policy demand. Certainly, in New York City, no one is talking about that now. As a matter of protest? Yes. As activism? Yes. But we have a new mayor, Eric Adams, who is anything but “defund the police.” Who are you disappointed in?

I still am disappointed in leadership and in my colleagues, because, ultimately, these conversations about “defund,” or this, that, and the other, are what is happening in public and popular conversations. Our job is to be able to engage in that conversation, to read what is happening, and to be able to develop a vision and translate it into a course of action. All too often, I believe that a lot of our decisions are reactive to public discourse instead of responsive to public discourse. And so, just because there was this large conversation about “defund the police” coming from the streets, the response was to immediately respond to it with fear, with pooh-poohing, with “this isn’t us,” with arm’s distance. So, then, what is the vision? That’s where I think the Party struggles.

Aren’t you seeing the response in City Hall now in the shape of Eric Adams?

Well, I think you also see it in the shape of the City Council that was elected. You have a record number of progressives. People often bring up the Mayor as evidence of some sort of decision around policing. I disagree with that assessment. I represent a community that is very victimized by a rise in violence. (And I represent Rikers Island!) What oftentimes people overlook is that the same communities that supported Mayor Adams also elected Tiffany Cabán. What the public wants is a strong sense of direction. I don’t think that in electing Mayor Adams everyone in the city supports bringing back torture to Rikers Island in the form of solitary confinement. What people want is a strong vision about how we establish public safety in our communities.

One of the ways that we engage is by backing some of the only policies that are actually supported by evidence to reduce incidents of violent crime: violence-interruption programs, summer youth employment. When we talk about the surge of violence happening right now, when I engage with our hospitals, doctors, social workers, everyone’s telling me that there’s so many things we’re not discussing. The surge in violence is being driven by young people, particularly young men. And we allow the discourse to make it sound as though it’s, like, these shady figures in the bush, jumping out from a corner. These are young men. These are boys. We’re also not discussing the mental-health crisis that we are experiencing as a country as a result of the pandemic.

Because we run away from substantive discussions about this, we don’t want to say some of the things that are obvious, like, Gee, the child-tax credit just ran out, on December 31st, and now people are stealing baby formula. We don’t want to have that discussion. We want to say these people are criminals or we want to talk about “people who are violent,” instead of “environments of violence,” and what we’re doing to either contribute to that or dismantle that.

I’ve never seen anybody so quickly become a lightning rod for right-wing criticism and obsession. Why do you think there’s such a fixation on you personally?

I think there’s just some surface-level stuff. And, to be honest, it’s not just the right wing. I was laughing because a couple of months ago someone showed me some of the news footage and coverage from the night that I was elected. And, obviously, I didn’t see any of it because I was, like, losing my mind.

But there was this footage, I think it was Brian Williams. And it was, like, breaking news: the third-most-powerful Democrat in the House of Representatives seems to have been unseated by this radical socialist. All the buzzwords that the right wing uses now were also completely legitimized by mainstream media on the night of the election. I never had a chance. People act as though there was something I could have done. There really wasn’t. It was kind of baked in from the beginning, and my choice was how to respond to that.

And I think because I respond to it differently, that increases a certain level of novelty, which then increases interest. But then there’s also just the basic stuff. I’m young, I’m a woman, I’m a woman of color. I’m not liberal in a traditional sense. I’m willing to buck against my own party, and in a real way. And I’m everything that they need. I’m the red meat for their base.

Do you worry sometimes that you take the bait too much or poke the bear in a way that might not be, in retrospect, something you should’ve done? Like, for example, the Met Gala, the “Tax the Rich” dress, or your response to the really weird tweet about your boyfriend’s feet?

All the time. Every day you make decisions, and you have to make decisions about whether it’s a good idea to go after this or if it’s a bad idea to go after it. Sometimes you make good decisions. Sometimes you make less-than-optimal ones. And then you reflect on them and you try to kind of sharpen your steel.

What were the less-than-optimal ones?

Everything has a different goal, right? And so, if you’re at home on Twitter, or if you’re at home on TV, there are some things that are not for you. There are some things I do that you don’t like that are not intended for you to like, such as what happened with the Met Gala. There are a lot of folks who did not like that. There were some “principled leftists” who didn’t like that. But, when you look at my community, it’s not a college town, a socialist, leftist, academic community. It’s a working-class community that I’m able to engage in a collective conversation about our principles. And, honestly, there’s a response to that in some circles online that may be negative, but in my community the response was quite positive.

The response to the Met Gala was positive in your community? How did you feel it?

Yeah. Because sometimes you just need to give a little Bronx jeer to the rich and to the spectacle. You need to puncture the façade. My community and my family—we’re postal workers, my uncle is a maintenance man, my mom’s a domestic worker. Sometimes you just need to have that moment.

It is a bizarre psychological experience to live specifically now in 2022. We’re not even talking about a culture of celebrity. We’re talking about a culture of commodification of human beings, from the bottom all the way to the top. And there’s absolutely a bizarre psychological experience of this that also plays into these decisions. For example, like what happened in responding to these bizarre things, like about my boyfriend’s feet. I’ve felt for a long time that we need to talk about the bizarre psychological impulses underpinning the right wing.

It’s not “politically correct” to be able to talk about these things, but they are so clearly having an obvious impact on not just our public discourse but the concentration of power. We have to talk about patriarchy, racism, capitalism, but you’re not going to have those conversations by using those words. You have to have those conversations by really responding in uplifting moments. I don’t really care if other people understand it. Sometimes what seems to some folks a moment that’s gauche or something, I often do it with the intention of exposing cultural or psychological undercurrents that people don’t want to talk about. Which, by the way, is why I think sometimes people read these moments as gauche or low-class or whatever they may be. And sometimes how I feel is, if I’m just going to be this, like, commodified avatar thing, then I’m going to play with it, like a toy.

It’s a rough thing to deal with.

Yeah. It’s awful.

One of the cudgels used by the right these days, and not only the right, is fear about cancellation and “wokeness.” We’ve even heard members of the House give speeches about the dangers of so-called cancel culture. And, at the same time, it does seem like norms around speech are changing around fears of online backlashes. I know you’ve criticized that term, “cancel culture,” even dismissed it, but you did so in a tweet.

You look at the capture of power in the right wing, the ascent of white nationalism, the concentration of wealth. You cannot really animate or concentrate a movement like that—you can’t coalesce it into functional political power—without a sense of persecution or victimhood. And that’s the role of this concept of cancel culture. It’s the speck of dust around which the raindrop must form in order to precipitate takeovers of school boards, pushing actual discourse out of the acceptable norms, like in terms of the 1619 Project or getting books banned from schools. They need the concept of cancel culture, of persecution, in order to justify, animate, and pursue a political program of takeover, or at least a constant further concentration of their own power.

You talk about cancel culture. But notice that those discussions only go one way. We don’t talk about all the people who were fired. You just kind of talk about, like, right-leaning podcast bros and more conservative figures. But, for example, Marc Lamont Hill was fired [from CNN] for discussing an issue with respect to Palestinians, pretty summarily. There was no discussion about it, no engagement, no thoughtful discourse over it, just pure accusation.

Last month, an ex-staffer of New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s told the New York Post that you could mount “a very, very credible challenge and quite likely beat her.” How do you feel about that? How do you view your political future?

I’m not trying to be, like, “I’m not like the other girls.” I’m not trying to position myself in that way. But I don’t think that I make these kinds of decisions as if I’m operating with some sort of ten-to-fifteen-year plan, like a lot of people do. Half this town, if not more, has been to a fancy Ivy League school. And so, as a consequence, everyone is, like, what chess pieces are being put down for what specific aspiration? I make decisions based on where I think people are and what we’re ready for, particularly as a movement. I think a lot of people sometimes make these decisions based on what they want, right? What I want is a lot more decentralized. I think it’s a lot more rooted in mass movements.

Could you see yourself walking away from public office entirely and going to a life of mass movements?

I think about it all the time. When I entertain possibilities for my future, it’s like anybody else. I could be doing what I’m doing in a little bit of a different form, but I could also not be in elected office as well. It could come in so many different forms. I wake up, and I’m, like, what would be the most effective thing to do to advance the power and build the power of working people?

Well, do you wake up sometimes in your Capitol Hill apartment and say, What the hell am I doing here? I’m one representative out of hundreds. I’m in a gridlocked situation. I’m not effecting the change I want to, and I’d rather join, or lead, or help lead a movement outside of government?

I’ve had those thoughts, absolutely. We all have different options in front of us. And the choice of what option we take at any given point is a reflection of all of those conditions, our motivations, all of those things. And there are times when I’m cynical and I sometimes fall into that. I’m just, like, “Man, maybe I should just, like, learn to grow my own food and teach other people how to do that!”

But I also reject the total cynicism that what’s happening here is fruitless. I’ve been in this cycle before in my life, before I even ran for office, before it was even a thought.

The social-media folks at The New Yorker invited people to propose questions for you via Instagram. Hope is the theme that is the center of almost all of these. If I can distill them, the most basic question is, What would you say to people, particularly young people, who have lost hope?

I’ve been there. And what I can say is that, when you’re feeling like you’ve lost hope, it’s a very passive experience, which is part of what makes it so depressing.

And that’s what I had to go through. There was all this hope when Obama was elected, in 2008. And, at the end of the day, a lot of people that had hope in our whole country had those hopes dashed.

I graduated. My dad died. My family had medical debt, because we live in the jankiest medical system in the developed world. My childhood home was on the precipice of being taken away by big banks. I’d be home, and there’d be bankers in cars parked in front of my house, taking pictures for the inevitable day that they were going to kick us out.

I was supposed to be the great first generation to go to college, and I graduated into a recession where bartending, legitimately, and waitressing, legitimately, paid more than any college-level entry job that was available to me. I had a complete lack of hope. I saw a Democratic Party that was too distracted by institutionalized power to stand up for working people. And I decided this is bullshit. No one, absolutely no one, cares about people like me, and this is hopeless. And I lost hope.

How did that manifest itself?

It manifested in depression. Feeling like you have no agency, and that you are completely subject to the decisions of people who do not care about you, is a profoundly depressing experience. It’s a very invisibilizing experience. And I lived in that for years. This is where sometimes what I do is speak to the psychology of our politics rather than to the polling of our politics. What’s really important for people to understand is that to change that tide and to actually have this well of hope you have to operate on your direct level of human experience.

When people start engaging individually enough, it starts to amount to something bigger. We have a culture of immediate gratification where if you do something and it doesn’t pay off right away we think it’s pointless.

But, if more people start to truly cherish and value the engagement and the work in their own back yard, it will precipitate much larger change. And the thing about people’s movements is that the opposite is very top-down. When you have folks with a profound amount of money, power, influence, and they really want to make something happen, they start with media. You look at these right-wing organizations, they create YouTube channels. They create their podcast stars. They have Fox News as their own personal ideological television outlet.

Legitimate change in favor of public opinion is the opposite. It takes a lot of mass-public-building engagement, unrecognized work until it gets to the point that it is so big that to ignore it threatens the legitimacy of mass-media outlets, institutions of power, etc. It has to get so big that it is unignorable, in order for these positions up top to respond. And so people get very discouraged here.

Going forward, what do you think is the optimal role for you to play?

With the Climate Justice Alliance, some communities here at home say that they don’t talk about leadership, they talk about being leaderful. And I think that people’s movements, especially in the United States, are leaderful. And we’re getting more people every day. The untold story is actually the momentum of what is happening on the ground. You have Starbucks that just unionized its first shops in Buffalo. I went up there to visit them. Sure, I went over there to support a mayoral election which didn’t ultimately pan out, but also to support a lot of what was going on. I would argue that if it wasn’t for that mayoral election and the amount of intensity and organizing and hope and attention, a lot of these workers who were organizing may have given up.

There is no movement, there is no effort, there is no unionizing, there is no fight for the vote, there is no resistance to draconian abortion laws, if people think that the future is baked in and nothing is possible and that we’re doomed. Even on climate—or especially on climate. And so the day-to-day of my day job is frustrating. So is everyone else’s. I ate shit when I was a waitress and a bartender, and I eat shit as a member of Congress. It’s called a job, you know?

So, yes, I deal with the wheeling and dealing and whatever it is, that insider stuff, and I advance amendments that some people would criticize as too little, etc. I also advance big things that people say are unrealistic and naïve. Work is like that. It is always the great fear when it comes to work or pursuing anything. You want to write something, and, in your head, it’s this big, beautiful Nobel Prize-winning concept. And then you are humbled by the words that you actually put on paper.

And that is the work of movement. That is the work of organizing. That is the work of elections. That is the work of legislation. That is the work of theory, of concepts, you know? And that is what it means to be in the arena.

[David Remnick has been editor of The New Yorker since 1998 and a staff writer since 1992. He is the author of “The Bridge: The Life and Rise of Barack Obama.”]

Spread the word