When Texas Republicans redrew their state’s congressional map earlier this year, they took what had been one of the most competitive and politically interesting maps in the country and, through discrimination against fast-growing racial and ethnic minorities, transformed it into one of the most boring and least dynamic. The Department of Justice sued Texas this week, alleging that the legislature's gerrymander is intentionally racially discriminatory and violates the Voting Rights Act. We break down how Texas did it.

The Old Map

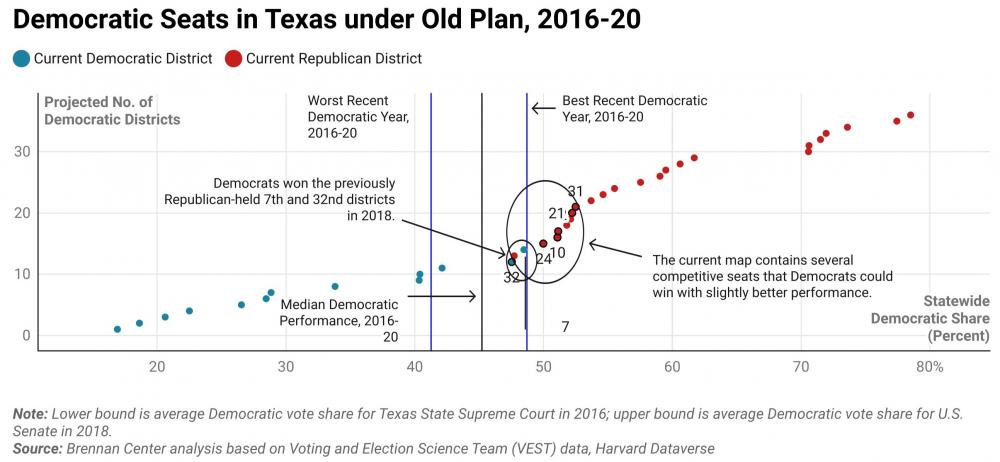

During the last decade, Texas used a congressional map drawn initially by the Republican legislature in 2011 and then partially redrawn by courts to remedy findings of racial discrimination. Despite the court-ordered fixes, the map remained an aggressive gerrymander, with Republicans holding a wildly disproportionate 25–11 edge in the state’s congressional delegation for almost all of the decade.

But gerrymandering can be complicated in a state that's growing and shifting demographically as rapidly as Texas is, and it turned out that Republicans had overreached when they drew the map in 2011. Instead of concentrating Republican voters to guarantee ultra-safe seats, they tried to maximize seat share by spreading Republican voters across a large number of districts. That turned out to be a serious miscalculation as urban and suburban districts grew demographically diverse and as white suburban voters shifted in large numbers toward Democrats. By 2018, Democrats were able to flip two Republican-held suburban seats and came within a hairbreadth of winning several others. Republicans ended the decade hanging on to a 23–13 advantage, but just barely.

The New Map

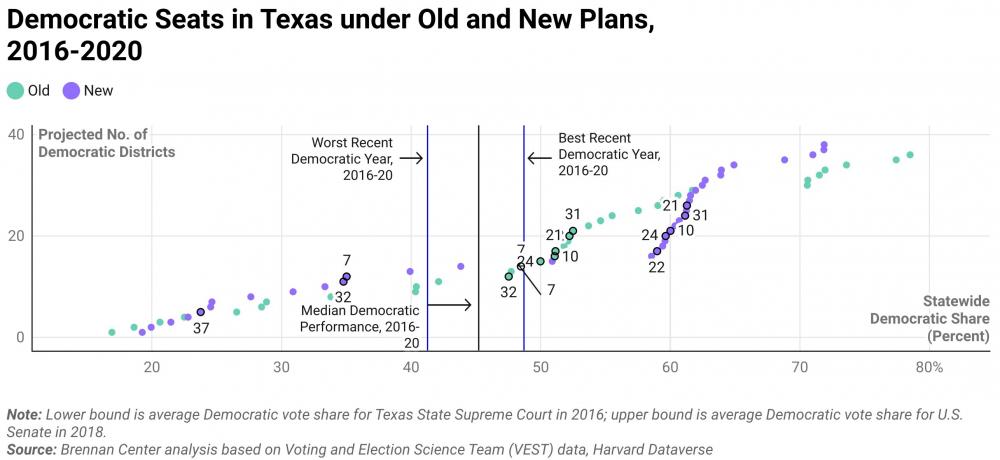

This decade, Republicans shifted tactics. Rather than target Democratic seats, they would shore up the existing gerrymander, making Republican seats safer. The results are illustrated in the chart below.

The chart’s green curve shows districts before redistricting. Under the old map, the 7th District and 32nd District, two suburban seats picked up by Democrats in 2018, were fiercely competitive and vulnerable to flipping back to Republicans, especially if Republicans were to make inroads with non-white voters. More problematic from the standpoint of Republicans, the green curve also shows that a number of Republican districts were competitive for Democrats if they could find a way to improve on Senate candidate Beto O’Rourke’s 2018 performance.

By contrast, the chart’s purple curve shows how the 2021 redistricting upended the map. By re-gerrymandering, Republicans were able to lock in a lopsided 24–14 advantage for Republicans in a state that is increasingly becoming a central battleground. To be favored to win more seats, Democrats would need to win 58 percent or more of the statewide vote — something improbable for the foreseeable future.

One part of the shoring up of the map occurred in central Texas. Dividing heavily Democratic Austin among multiple districts was key to the 2011 GOP strategy of minimizing the number of Democratic seats. The Republicans’ 2011 map infamously splintered the city among six districts. But since the last round of redistricting, Austin’s population has boomed and, critically, became even more loyally Democratic. The once safely Republican districts around Austin grew dangerously competitive.

To deal with their Austin problem, Republicans placed the bulk of Austin in a new heavily Democratic district — essentially ceding one district to Democrats in order to shore up multiple adjacent GOP districts. As shown in the purple curve in the chart above, the change had its intended effect. The new Austin-based 37th District is one of the most Democratic in the state. Meanwhile, the 10th and 21st Districts, which had once been highly competitive for Democrats, both became much more safely Republican, as did the slightly less competitive 25th and 31st Districts.

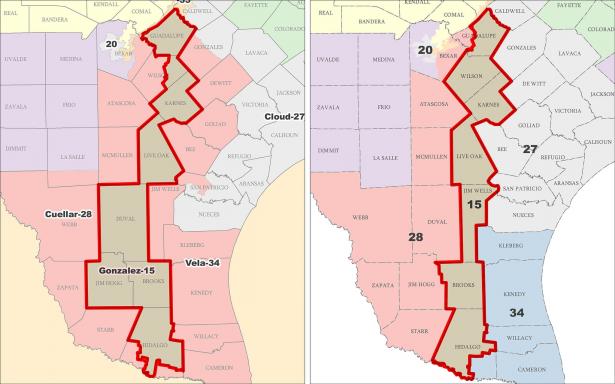

But if Republicans were willing to create a heavily white Democratic district in central Texas, they took a different tack when it came to communities of color. Despite the fact that non-white communities were responsible for 95 percent of the state’s population growth last decade, Republicans refused to create additional new minority opportunity districts in either the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex or Houston. In addition, they aggressively broke up diverse suburban districts where multiracial coalitions had come close to winning power last decade.

The changes had both a political effect and a racial one. Suburban communities of color in places like Fort Bend County were ruthlessly divided — some voters of color were kept in existing districts, while others were surgically moved into Democratic-held swing districts. As a result, once highly competitive, white-majority swing districts became deeply Democratic ones under the new map. Those voters of color who were shifted out of suburban districts were replaced with whiter exurban or rural voters, turning those districts solidly Republican even though they continue to have significant non-white populations.

Multiple lawsuits, including one by the Biden administration, are pending to challenge the racially discriminatory aspects of the new Texas map. But, even if successful, litigation challenging maps may take years — and multiple election cycles — to fully wend its way through the courts. And unless Congress strengthens protections for communities of color with bills like the Freedom to Vote Act and John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, it may be difficult to fully remedy discrimination. In the meantime, while Texans wait on courts and Congress, Texas will have one of the least competitive maps in the nation, and its booming communities of color once again will be shut out of their fair share of power.

Michael Li serves as senior counsel for the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program, where his work focuses on redistricting, voting rights, and elections. Prior to joining the Brennan Center, Li practiced law at Baker Botts L.L.P. in Dallas for ten years. He was the author of a widely cited blog on redistricting and election law issues that the New York Times called “indispensable.” He is a regular writer and commentator on election law issues, appearing on PBS Newshour, MSNBC, and NPR, and in print in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, USA Today, Roll Call, Vox, National Journal, Texas Tribune, Dallas Morning News, and San Antonio Express-News, among others.

In addition to his election law work, Li previously served as executive director of Be One Texas, a donor alliance that oversaw strategic and targeted investments in nonprofit organizations working to increase voter participation and engagement in historically disadvantaged African American and Hispanic communities in Texas.

Li received his JD with honors from Tulane Law School and an undergraduate degree in history from the University of Texas at Austin.

Julia Boland is a research and program associate in the Democracy Program, where she focuses on redistricting and democracy reform. Prior to joining the Brennan Center, Boland interned for Kids in Need of Defense and Equal Justice Works. Boland previously worked as a research assistant and student supervisor at the Wesleyan Media Project, a non-partisan research initiative that provides real-time analysis of political advertising data with the goal of enhancing government transparency.

Spread the word