A game, the philosopher Bernard Suits wrote, is “the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.” It’s one thing to shove a fistful of chess pieces across the board to surround the enemy king. It’s quite another to get them there in accordance with the ancient game’s intricate rules, and while your grandmaster opponent tries to do the same.

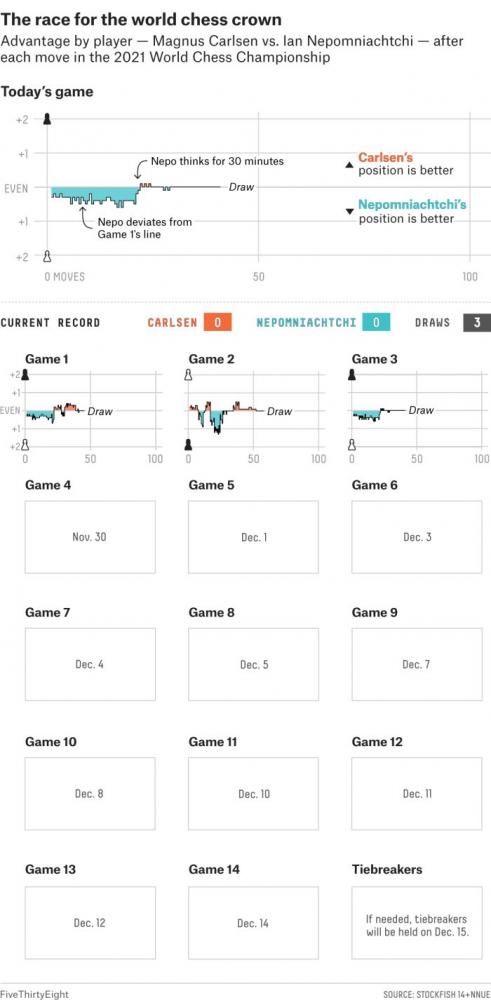

Magnus Carlsen of Norway and Ian Nepomniachtchi of Russia are currently overcoming obstacles in a glass box in Dubai, competing for the World Chess Championship. Neither has yet been able to surround the other’s king. After a 41-move draw over less than three hours in Sunday’s Game 3, their best-of-14-game match remains level at 1.5-1.5. It has now been 1,830 days since anyone won a regulation game in the World Chess Championship.

Nepomniachtchi moved first, minding the white pieces. The grandmasters played the Ruy Lopez opening, specifically its anti-Marshall variation, visiting once again some of the most well-trod ground in chess theory — “the mother opening,” per former world champion Viswanathan Anand on the official broadcast. Indeed, the first seven moves exactly matched those of Game 1.

For nearly the entire game, both players maneuvered their pieces nimbly and quickly, clearly familiar with the theory, and the computer’s all-seeing eye hardly blinked on Sunday, as the position was essentially level from start to finish.

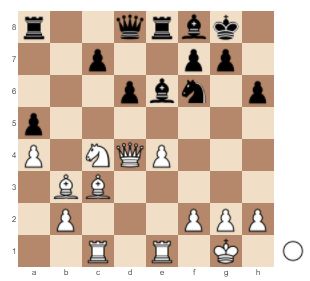

The famously fast Nepomniachtchi thought for 30 minutes in the position below, his 21st move, the longest he’s spent by far on any move in the match, and perhaps the game’s only speed bump.

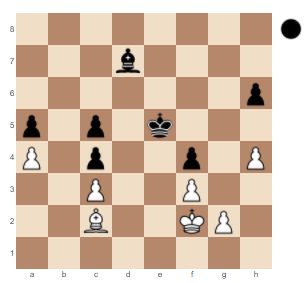

He eventually pushed his pawn forward to h3. A few moves later, queens and minor pieces were traded off the board in a flurry, dulling whatever little edge was present in the game. The rooks left, too, in short order, and the grandmasters shook hands and agreed to a draw in the position below, neither able to make further progress.

While a string of chess draws could be seen as boring, or as a failure of attacking prowess, it should also be seen as a great success, a testament to the deep preparation and precise execution of the game’s master craftsmen — a drawn tug of war not between weaklings but between Goliaths.

“This is the current status of chess theory,” Nepomniachtchi said after the game. “It’s hard to find some advantage.”

Why do we volunteer to overcome games’ unnecessary obstacles? We play games “because we want to have a certain kind of struggle,” writes C. Thi Nguyen, a philosopher at the University of Utah. “And we can do so for the sake of aesthetic experiences of striving — of our own gracefulness, of the delicious perfection of an intellectual epiphany, of the intensity of the struggle, or of the dramatic arc of the whole thing.”

The match rests tomorrow, and Game 4 begins Tuesday at 7:30 a.m. Eastern. We’ll be covering the entire dramatic arc, drawish or otherwise, here and on Twitter, and we await the delicious perfection.

Oliver Roeder is a journalist and author in New York City. Recently, he has been a Nieman Fellow at Harvard studying artificial intelligence, and a senior writer and the puzzle editor at FiveThirtyEight. Find him on Twitter or send him an email. He is especially interested in games and competitive subcultures, political strategy, art and its market, and our artificially intelligent future. He holds a PhD in economics with a focus on game theory. Sometimes he writes crossword puzzles.

He is the author of:

Seven Games: A Human History (W.W. Norton, forthcoming Jan. 2022) -- for millennia, human beings have played games. For decades, computer scientists have developed artificial intelligence to beat the best human players—in checkers, chess, Go, backgammon, poker, Scrabble, and bridge, among others. This book is a narrative history of that human-machine collision and the battles for gaming supremacy. It is also an essay on what artificial intelligence and games mean for our species and its future.

The Riddler: Fantastic Puzzles from FiveThirtyEight (W.W. Norton, 2018) -- A collection of his weekly math columns and the first book under the FiveThirtyEight banner. Will Shortz called it “a modern, smart puzzle book, unlike anything I’ve seen before, whose math and logic challenges will stretch your brain in new ways.”

Five ThirtyEight covers sports, politics and science. We use data and evidence to advance public knowledge — adding certainty where we can and uncertainty where we must.

Spread the word