Investigation shows scale of big food corporations' market dominance and political power

Illustrations by Julia Louise Pereira

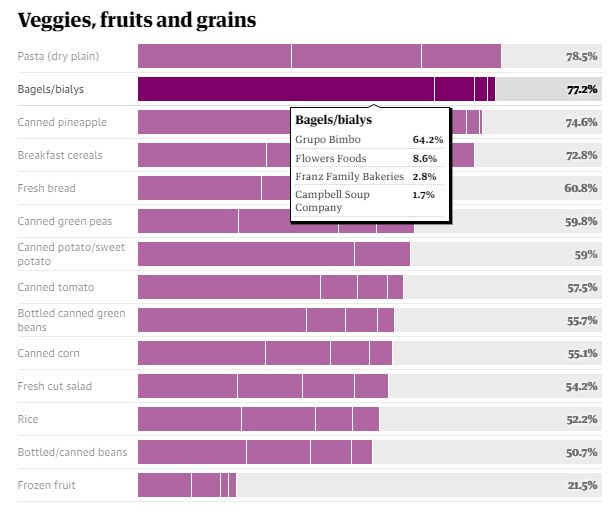

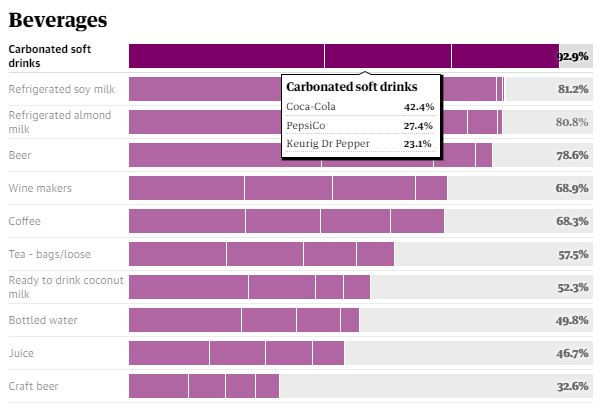

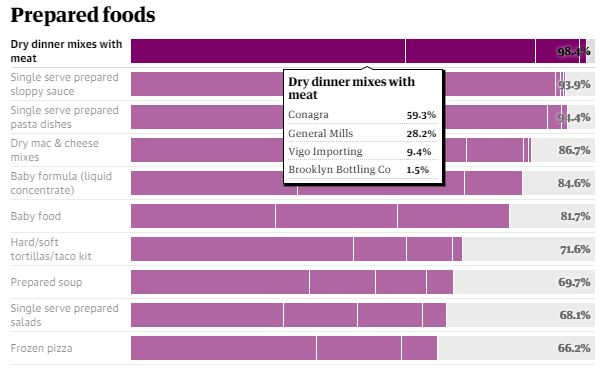

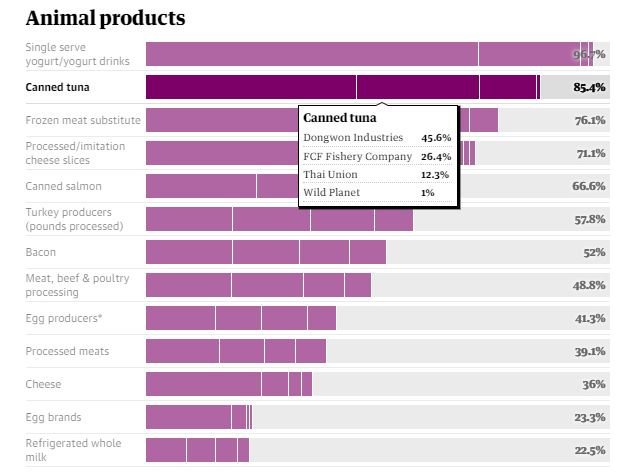

A handful of powerful companies control the majority market share of almost 80% of dozens of grocery items bought regularly by ordinary Americans, new analysis reveals.

A joint investigation by the Guardian and Food and Water Watch found that consumer choice is largely an illusion – despite supermarket shelves and fridges brimming with different brands.

In fact, a few powerful transnational companies dominate every link of the food supply chain: from seeds and fertilizers to slaughterhouses and supermarkets to cereals and beers.

The size, power and profits of these mega companies have expanded thanks to political lobbying and weak regulation which enabled a wave of unchecked mergers and acquisitions. This matters because the size and influence of these mega-companies enables them to largely dictate what America’s 2 million farmers grow and how much they are paid, as well as what consumers eat and how much our groceries cost.

It also means those who harvest, pack and sell us our food have the least power: at least half of the 10 lowest-paid jobs are in the food industry. Farms and meat processing plants are among the most dangerous and exploitative workplaces in the country.

Overall, only 15 cents of every dollar we spend in the supermarket goes to farmers. The rest goes to processing and marketing our food.

The Guardian and Food and Water Watch investigation into 61 popular grocery items reveals that the top companies control an average of 64% of sales.

We found that for 85% of the groceries analysed, four firms or fewer controlled more than 40% of market share. It’s widely agreed that consumers, farmers, small food companies and the planet lose out if the top four firms control 40% or more of total sales.

Our investigation is based on the analysis of market share data from thousands of supermarkets across the US.

“It’s a system designed to funnel money into the hands of corporate shareholders and executives while exploiting farmers and workers and deceiving consumers about choice, abundance and efficiency,” said Amanda Starbuck, policy analyst at Food & Water Watch.

The consolidation runs deep: four firms or fewer controlled at least 50% of the market for 79% of the groceries. For almost a third of shopping items, the top firms controlled at least 75% of the market share.

For instance, PepsiCo controls 88% of the dip market, as it owns five of the most popular brands including Tostitos, Lay’s and Fritos. Ninety-three per cent of the sodas we drink are owned by just three companies. The same goes for 73% of the breakfast cereals we eat – despite the shelves stacked with different boxes.

Big food is getting bigger

For shoppers, it might seem like choices galore at the store, but most of our favorite brands are actually owned by a handful of food giants, including Kraft Heinz, General Mills, Conagra, Unilever and Delmonte.

Kraft Heinz, the result of a $63bn mega-merger in 2015, which was backed by Warren Buffett and a Brazilian private equity firm, appears 12 times in the top 4 firms for groceries, with products ranging from bacon, sour cream and coffee to frozen meat substitutes and fruit juice.

The big firms are helped by so-called category captains who represent leading brands or manufacturers and work with major retailers to decide which products get prominent spots on our supermarket shelves. And then there’s the slotting fees – payments by big-brand manufacturers for eye-catching product placement. This makes it very hard for new independent brands to get a break. And when they do get a tiny foothold, it often doesn’t last.

For example, while hipsters and old-school beer enthusiasts have contributed to a boom in local craft beers, the Belgian company Anheuser-Busch InBev acquired 17 formerly independent craft breweries between 2011 and 2020. It might not be clear to consumers from the labels, but the company owns more than 600 brands, including the mainstream favorites Budweiser, Michelob and Beck’s.

Another source of confusion is private labels – supermarkets' own brands, of which little is known about the producer – which appeared in the top four of 77% of the groceries we looked at. For frozen fruits like the mixed berries used for smoothies and desserts, private labels account for 66% of the market share, as well as 56% of refrigerated whole milk and 54% of eggs sales.

Which of these cereals do you think is owned by on of the four huge companies that dominate the market?

Food giants General Mills, Kellogg and Post own all but one of these brands.

Millions spent on lobbying politicians

The economic power of the corporations has contributed to their growing political power, which in turn has led to laws that put profits before food and worker safety, consumer rights and sustainability.

During the 2020 election cycle, the food industry spent $175m on political contributions, including lobbying by PACs and individuals and other efforts.

The money came from every part of the food chain, including dairy, eggs, poultry, meat processing, farm bureaus, sugar cane, crop production and supermarkets.

About two-thirds went to Republicans.

The 2020 total compares to just $29m spent during the 1992 election cycle, which means lobbying by the food industry has increased by sixfold in less than three decades as consolidation across the supply chain has boomed.

Supermarket chains dominate

Less competition among agribusinesses means higher prices and fewer choices for consumers – including where they can shop for food.

Until the 1990s, most people shopped in local or regional grocery stores. Now, just four companies – Walmart, Costco, Kroger and Ahold Delhaize – control 65% of the retail market.

“Corporate consolidation can drive up food prices and reduce access to food,” said Starbuck. “Supermarket mergers drive out smaller, mom-and-pop grocers and regional chains. We have roughly one-third fewer grocery stores today than we did 25 years ago, according to the US census bureau.”

As countless mom-and-pop stores struggled to stay afloat during the pandemic lockdowns, revenue for Walmart US hit $341bn - almost 3% higher than the previous year.

Grocery chains and superstores are also the main beneficiaries of government aid for Americans struggling to feed their families. In 2020, 82% of all food stamps were spent in supermarkets and superstores like Krogers, Walmart, Costco and Sam’s Club, which means the taxpayer contributed $64bn to their revenue.

The meat market – and sticky commodity prices

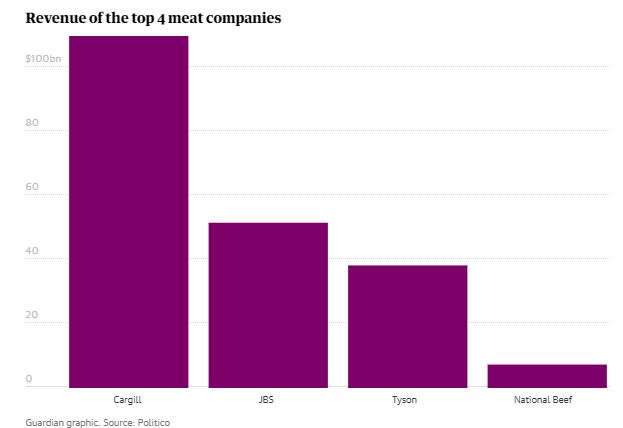

A spate of mega-mergers means that meatpacking plants are now controlled by just a handful of multinationals including Tyson, JBS, Cargill and Smithfield (now owned by the Chinese multinational WH Group). Proponents of capitalism claim mergers and acquisitions generate efficiencies that cut costs for farmers and benefit consumers by keeping prices down. But the tight grip these companies have over the industry means farmers have little choice about whom they sell to and how their animals are raised.

Consumers pay more while profits for mega meat processors are booming: in 2020, the Brazilian firm JBS reported $51bn in revenue – a 32% rise compared with the previous year. China is driving much of the company’s growth, and JBS accounted for 50% of beef exports from the US last year. The proportion of arable land dedicated to producing meat is expanding but this is largely to feed consumers overseas. Per capita meat production flatlined in the US between 2005 and 2020, while the value of exports almost doubled.

Consumers are also hurt by so-called sticky prices. Commodity prices can rise due to shortages caused by unexpected events such as floods or drought that disrupt the supply chain – which happened at the start of the pandemic. When this happens, supermarkets are quick to increase prices to ensure profit margins remain intact, but when commodities go down, consumer prices are often much slower to decrease.

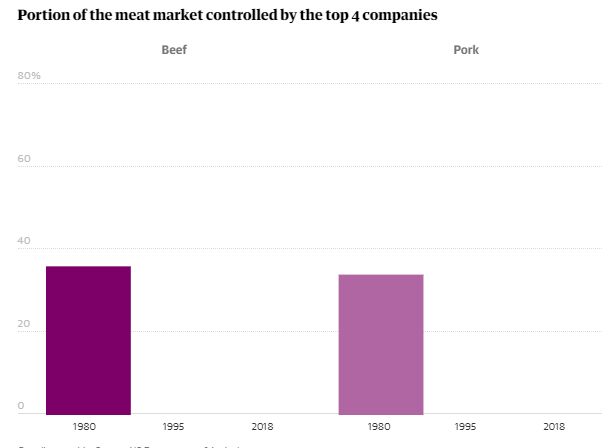

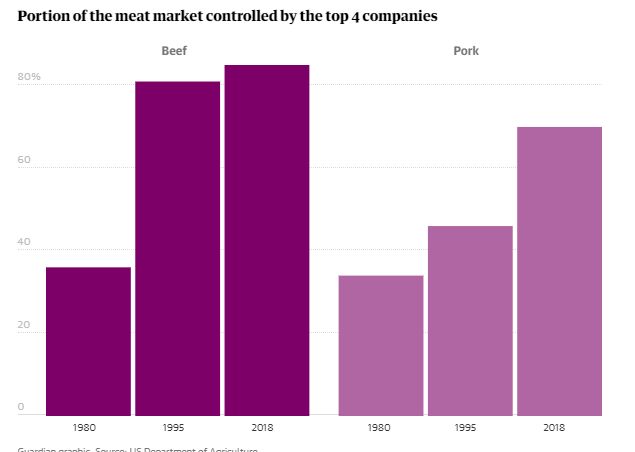

Forty years ago, about a third of the beef and pork processing industry was controlled by the top four firms.

After a spate of mega-mergers, more than 80% of beef processing and 70% of pork processing is controlled by four multinational giants.

In 2017, these top firms had a combined annual revenue of $207bn.

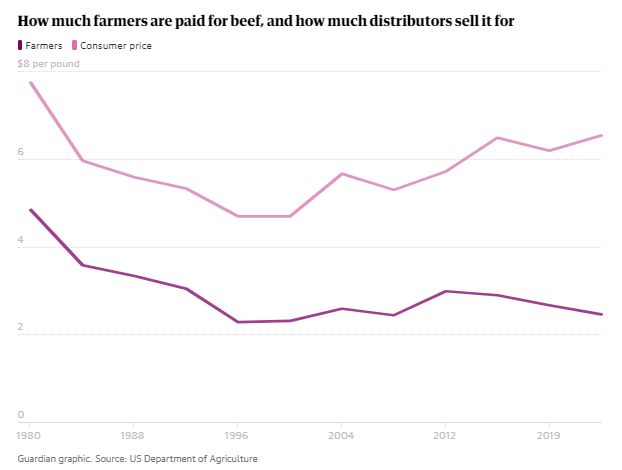

Meanwhile, farmers and consumers lost out.

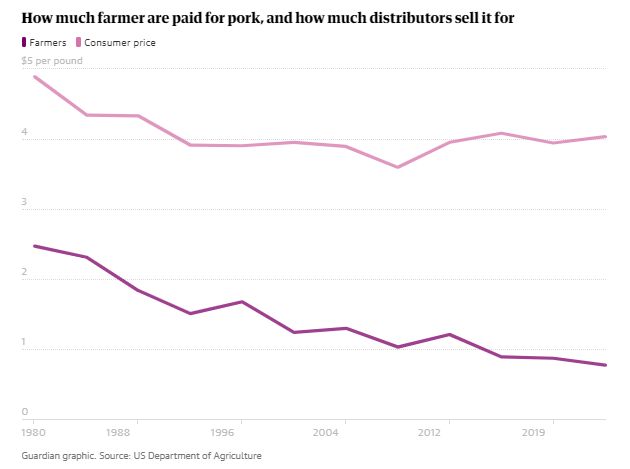

In the past forty years, these huge corporations have been paying farmers less and less for beef and selling it to consumers at increasing prices.

These huge companies have also been paying farmers less for port, while selling it at the same price for the past 30 years.

Farmers squeezed ... and desperate

America’s farmers have become increasingly dependent on government aid.

Farmers received $424.4bn in subsidies between 1995 and 2020, of which 49% were for just three crops: corn, wheat and soybeans, according to the Environmental Working Group. Corn subsidies are the largest by a long way – $116.6bn – accounting for 27% of the total. Very little corn grown in the US is eaten these days. Instead, more than 99% goes into animal feed, additives like corn syrup used in sugary junk food and, increasingly, ethanol, which produces toxic air pollutants when burned with gasoline.

It’s a cruel paradox, according to some campaigners, as subsidies incentivise farmers to grow just a handful of cash crops, a practice that floods the market, depresses prices and keeps them hooked on government aid.

Commodity prices peaked in mid-2012 and plunged by about 50% by the end of 2019.

This is good news for big corporations like meat processors, as it reduces costs, but bad for many farmers: total farm debt has reached levels not seen since the 1980s farm crisis.

Advocates say that a toxic mix of financial woes, climate chaos and trade wars have contributed to a mental health crisis among farmers. At least 450 farmers died by suicide across nine midwestern states between 2014 to 2018, according to the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. Calls to a crisis hotline operated by Farm Aid, a non-profit agency trying to help farmers keep their land, almost doubled over the same period. In 2020, 552 farmers filed for bankruptcy – 7% fewer than the previous year, as commodity prices and government aid increased during the pandemic, but still the third-highest figure over the last decade.

“The economic power of these corporations enables them to wield huge political influence, so we have a system in which farmers are on a treadmill just trying to stay afloat. Basically there’s a handful of individuals in the world, mostly white men, who make money by dictating who farms, what gets farmed and who gets to eat. Consumer choice is an illusion; the transnationals control everything in this extractive agricultural model,” said Joe Maxwell, president of Family Farm Action.

Less than a third of farms – mostly big ones – benefit from USDA subsidies in part because the system has a long history of descrimination against farmers of color and small farms without the time, resources or expertise to dedicate to online applications.

Food industry workers: low pay, high hazards

At least half of the 10 lowest-paid jobs in the US are in the food industry, and they rely disproportionately on federal benefits. Walmart and McDonald's are among the top employers of beneficiaries of food stamps and Medicaid, according to a 2020 study by a non-partisan government watchdog.

Even before the pandemic, farms were among the most dangerous workplaces in the country, where low paid workers have little protection from long hours, repetitive strain injuries, exposures to pesticides, dangerous machinery, extreme heat and animal waste. Between 50% and 75% of the country’s 2.5 million farmworkers are undocumented migrants who have few labor rights and limited access to occupational healthcare.

Covid exposed and exacerbated the risks faced by frontline food workers, especially those working in meatpacking plants. As of last week, at least 58,898 meatpacking plant workers had tested positive for Covid, according to data collected by the Food and Environment Reporting Network (Fern), and many of the outbreaks led to community spread in rural areas. This is a massive undercount as the majority of states do not collect or share the data, nor do the big companies.

“The meatpacking industry is much more dangerous now than in the 1990s, and the biggest factors are consolidation and cutting corners of worker safety,” said Debbie Berkowitz, director of the worker health and safety program at the National Employment Law Project.

Environmental impacts

About half of the planet’s land and 70% of freshwater withdrawals are for farming, which is increasingly industrialized.

Industrial agriculture is focussed on extracting maximum profits for minimum costs – an exploitative model with grave consequences for animal welfare, water, land and global heating.

Agriculture is responsible for more than a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, making food production a major contributor to the climate crisis. Across the board, the carbon footprint for animal-based foods – beef, lamb, chicken, cheese – is higher than for plant based food, which is mostly due to the consequences of deforestation to create space to grow feed crops, fertilizer used for these crops and methane emissions.

Despite the community, environmental and economic benefits of supporting local sustainable producers, transporting food is a very small contributor to greenhouse gases: it’s really what you eat, not where it comes, from that’s key to reducing your dietary carbon footprint.

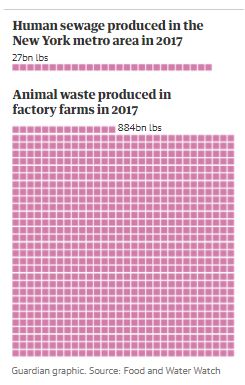

Here in the US, there were 1.6bn animals living on 25,000 factory farms in 2017 – a 14% rise in just five years. Together, these animals produced about 885bn pounds of manure annually – equivalent to the human sewage generated by residents of 30 New York Cities.

Incentivising farmers to grow the same crops has reduced the productivity of some of the country’s most fertile lands, as monocropping depletes soil of nutrients and can lead to significant erosion. The practice requires synthetic fertilizers to compensate for the lost nutrients, and pesticides to combat fungi and insect predators that thrive in these conditions. Indigenous and subsistence farmers have always rotated multiple crops because it’s the best way of ensuring healthy soil and good yields.

Agricultural runoff is now responsible for 80% of excessive nutrients in our freshwater and oceans, which cause dense growth of plant life like algae that block oxygen from reaching fish and other animals.

In 2019, agriculture and aquaculture were identified as a threat to 24,000 of the almost 28,000 species threatened with extinction, according to the IUCN Red List.

What can be done?

In the 1970s, President Richard Nixon’s agriculture secretary told farmers to “get big or get out”.

This investigation has examined the far-reaching consequences of government support - political and economic - for big corporations that now dominate every part of the food chain.

Last week Joe Biden signed an executive order to tackle the rampant concentration across the US economy - including food and farming. Biden called on government agencies to enforce existing antitrust laws and consider rolling back recent mega-mergers which boosted profits and power for a handful of corporations while hurting the rest of us. The order specifically directs the USDA to take swift action to protect farmers including by making it easier for them to sue meat processors for alleged abuses.

But the problems in the current system run deep.

“From farm to fork, America’s food system has been rooted in the exploitation of women, Native Americans and people of color. This is at the heart of capitalist food politics – big corporations taking as much as they can and paying as little as possible for it,” said Raj Patel, academic and author of Stuffed and Starved: Markets, Power and the Hidden Battle for the World's Food System.

In addition to executive actions, which could be overturned by the next president, such deep-rooted injustices need sweeping reforms by Congress. But bills banning new mega-mergers and factory farms currently lack bipartisan support, despite public opinion supporting them.

It’s time to support small-scale regenerative farmers, regional food hubs and grocery coops, according to Starbuck. “Alternatives already exist. We just need to boost public funding and resources to help sustainable, affordable, more equitable food systems take root.”

In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is at 800-273-8255 and online chat is also available. You can also text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis text line counselor. In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org

How we did the research

The Guardian and Food and Water Watch selected a range of grocery categories to reflect everyday products Americans commonly buy.

The sales information comes from retail scanner data compiled by the market research firm IRI, a Chicago-based international company. Data obtained directly from IRI covers the majority of 2020; we also used IRI data published by Mintel Group reports (covering 2019) and the Market Share Reporter (covering 2017).

We calculated the ratio of sales of the top four – or fewer – companies in each food category compared with the rest. This calculation is a common yardstick to measure industry concentration. Brands and subsidiaries (including all mergers/acquisitions completed by June 2021) appear in the market share of their parent companies.

Markets where the top four companies account for more than 40% of sales are generally considered to be consolidated; those exceeding 60% are tight oligopolies or monopolies.

For the meat, beef and poultry processing categories, we used Ibis World’s estimate of total revenue in 2021.

Nina Lakhani is environmental justice reporter for Guardian US Twitter: @ninalakhani

Aliya Uteuova is a visual journalist who reports on environmental justice

Alvin Chang is a Guardian US data and visual reporter

Subscribe to The Guardian for facts’ sake

Tens of millions have trusted in us for high-impact journalism during times of crisis, uncertainty, solidarity and hope. And we’re just getting started. Show your support by becoming a digital subscriber today. No ads, no interruptions. Just quality, fiercely independent reporting and you can help power our work for centuries more.

Spread the word