‘The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there’. The opening sentence of L.P. Hartley’s The Go-Between (1953) has become a historical cliché. Yet contrary to its implications, the past has no independent existence, but is being continually updated by scholarly travelers: it is a constantly shifting territory, an endangered world plundered by souvenir-hungry historical tourists.

Since his death in 1727, Isaac Newton has been reborn in various incarnations that reflect the interests of their creators as much as the realities of his existence. His monument in Westminster Abbey records not only his contributions to physics, but also his commitment to biblical studies and the timetables of ancient chronology, while the posthumous statue in Trinity College Cambridge shows an enraptured Enlightenment gentleman wielding a prism like an orator’s baton. The tale of the falling apple began circulating only in the nineteenth century, and his alchemical interests were suppressed until the economist John Maynard Keynes unleashed a flurry of investigations after the Second World War.

Newton’s definitive biography remains Never at Rest (1980) by the American historian Richard Westfall, who subsequently undertook a prolonged psychoanalytical investigation of his authorial relationship with his subject. In an extraordinary article, Westfall outlined the conclusions he had drawn about himself. “Biography…cannot avoid being a personal statement,” he declared, confessing that he had painted “a portrait of my ideal self, of the self I would like to be.” As he continued soul-searching, he accused himself of resembling a puritanical Presbyterian elder determined to preserve unsullied Newton’s reputation as a scientific genius, and he admitted downplaying Newton’s thirty years of financial and political negotiations at the Mint.

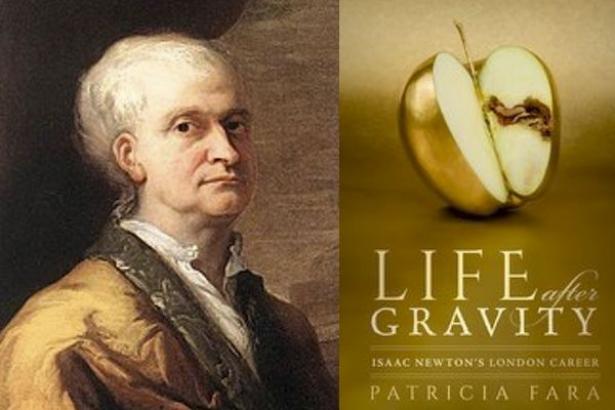

I hold no such qualms. Immersed in modern concerns about global capitalism and international exploitation, in Life after Gravity (2021) I explore Newton’s activities during those last three decades that so discomfited Westfall. Many scientists regard his London years as an unfitting epilogue for the career of an intellectual giant, but economists see matters differently. More interested in falling stock markets than in falling apples, they are untrammelled by assumptions that the life scientific is the only one worth living. According to them, once Newton had tasted fame and the possibilities of wealth, he wanted more of both. And that entailed moving to the capital, where he earned a fortune, won friends and influenced people. I can only speculate about reasons – professional insecurity, the anguish of an impossible love affair, private worries about intellectual decline as he aged – but Newton engineered his move with great care. Determined to make a success of his new life, he broke definitively away from provincial Cambridge with its squabbling academics, and dedicated himself to his new metropolitan existence.

While he worked at the Mint, Newton continued to confirm and refine his theories of the natural world, but he was also a member of cosmopolitan society who contributed to Britain’s ambitions for global domination. He shared the aspirations of his wealthy colleagues to make London the world’s largest and richest city, the center of a thriving international economy. Like many of his contemporaries, he invested his own money in merchant shipping companies, hoping to augment his savings by sharing in the profits (although he sustained a substantial loss during the South Sea Bubble crash of 1720).

An uncomfortable historical truth is often glossed over: until 1772, it was legal to buy, own, and sell human beings in Great Britain. Newton knew that the country’s prosperity depended on the international trade in enslaved people, and he profited by investing in companies that carried it out. For fine-tuning his gravitational theories, he solicited observations of local tides from merchants stationed in trading posts. And when he was meticulously weighing gold at the Mint, he must have been aware that it had been dug up by Africans whose friends and relatives were being shipped westward across the Atlantic, where they were forced to cultivate sugar plantations, labor down silver mines, and look after affluent Europeans.

National involvement in commercial slavery was a collective culpability, and there is no point in replacing the familiar “Newton the Superhuman Genius” with the equally unrealistic “Newton the Incarnation of Evil.” By exploring activities and attitudes that are now deplored, I aim not to condemn Newton, but to provide a more realistic image of this man who was simultaneously unique and a product of his times.

Newton was a metropolitan performer, a global actor who played various parts. Since theatricality was a favourite Enlightenment metaphor, I chose to experiment by structuring my narrative around a dramatic conversation piece by William Hogarth: The Indian Emperor. Or the Conquest of Mexico (1732). It is seeped in Newtonian references. For example, centrally placed on the mantelpiece, Newton’s marble bust gazes out across an elegant drawing room, while the royal governess bids her daughter to pick up a fan that has dropped to the floor through the power of gravity. On a small makeshift stage, four aristocratic children arranged in a geometric square perform a revived Restoration play about imperial conquest and the search for gold. Traveling round the picture – the room, the audience, the stage – as if I were a fly on its walls, I describe how Newton interacted with ambitious wheelers and dealers jostling for power not only in Britain, but around the entire world.

Newton may have been exceptional, but he can no longer be seen as William Wordsworth’s Romantic genius soaring in strange seas of thought alone, an abstract mind divorced from the mundane concerns that affect every human being. Ensconced in a powerful position, he took decisions and implemented policies that contributed to fostering the exploitation and disparity lying at the heart of modern democracy. As a privileged British academic, I benefit from being enmeshed within a global economic system that promotes inequality, and whose growth has been linked with the rise of science and the rise of empire since the mid-seventeenth century.

Exploring Hartley’s foreign country of the past can help to reveal how we have reached the present, but for me the main point of doing that is to improve the future. The current state of the world is not pre-ordained. Instead, multiple individual choices have shaped the direction humanity has collectively taken, and millions of others will affect what lies ahead. Ensuring a better future requires that everybody – you, me – take personal action. In writing this book, I have tried to analyse some of the ways in which our predecessors went wrong: we must avoid repeating their mistakes.

Patricia Fara, an Emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, UK, is the author of several acclaimed books on the history of science, including her award-winning Science: A 4000 Year History. Her latest publication, Life after Gravity: Isaac Newton’s London Career, will be published in the US in May 2021.

![]() History News Network depends on the generosity of its community of readers. If you enjoy HNN and value our work to put the news in historical perspective, please consider making a donation today!

History News Network depends on the generosity of its community of readers. If you enjoy HNN and value our work to put the news in historical perspective, please consider making a donation today!

Spread the word