One of the casualties from HBO Max becoming WarnerMedia’s number one priority is Cinemax, HBO’s somewhat unheralded sister network. As announced at the start of 2020, Cinemax will no longer work on original content—nor will the brand be folded into the company’s glitzy new streaming service. Now you might be thinking, “Wait, Cinemax has TV shows?!” and, well, fair—lots of people slept on The Knick, and fewer still could name three Cinemax original series. But the news also means that Warrior, a supremely kick-ass and criminally underappreciated martial arts Western based on the works of Bruce Lee, will struggle to fight another day.

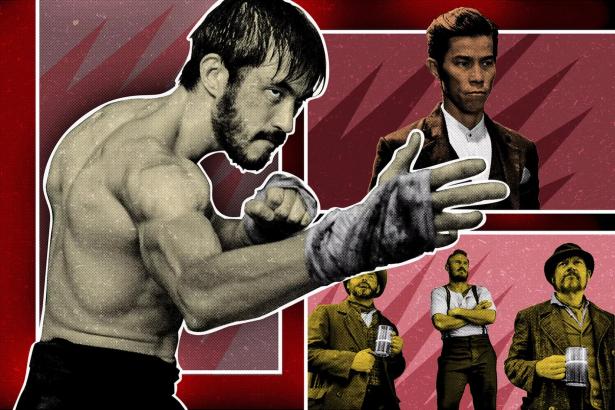

The series, which was brought to life by Bruce’s daughter, Shannon Lee, director of four Fast & Furious films, Justin Lin (as an executive producer), and Jonathan Tropper (creator of Cinemax’s Banshee, who serves as the showrunner), focuses on Chinese immigrant Ah Sahm (played by Andrew Koji, in a role Lee once envisioned for himself) as he arrives in San Francisco in 1875. Sahm, a proficient martial artist, is quickly sucked into Chinatown’s Tong Wars after joining the Hop Wei Tong, all while anti-Chinese sentiments grow more hostile in the city—particularly among members of the Irish working class, who believe that Chinese workers are taking jobs away from them. The vibe is very much “What if Peaky Blinders was racially diverse and half the characters could roundhouse kick you in the face?”

After introducing Sahm and the grimy streets of 19th-century San Francisco, Warrior quickly becomes a true ensemble piece—its deep roster of characters includes rival Tongs, brothel owners, policemen, businessmen, corrupt politicians, and aggrieved spouses of said corrupt politicians. To list every character and their relationships to one another would require an entirely new blog, but here are some standouts: Mai Ling, head of rival Tong the Long Zii, who is also [gasp] Sahm’s secret sister; Buckley, a Machiavellian deputy mayor whom everyone should be suspicious of because his name is Buckley; and Wang Chao, a man I can only describe as “Warrior’s answer to Varys and Littlefinger.”

Similar to the fourth season of Noah Hawley’s Fargo, Warrior explores America’s racial history and its intersection with the immigrant experience—it shows how, in a nation of immigrants, nonwhite people are seldom considered “American” by their white peers. But unlike Fargo Season 4, which is mired in too many overwrought monologues about America to have any fun, Warrior makes itself an extremely entertaining watch through the prioritization of bountiful ass-kicking. With Warrior, you’re guaranteed at least one epic action scene per episode, and one of the joys of the show is that each fight has its own unique flavor. In the hands of series fight coordinator Brett Chan, Warrior flexes a mix of different fighting styles and settings—from face-offs involving judo and taekwondo to street duels with hatchets and drunk Irish blokes bare-knuckle boxing outside a bar. It’s especially thrilling when these different fighting styles intersect; watching a racist Irishman get dropped like a sack of potatoes will never get old.

At the start of the second season, which premieres on Friday, the rival Tongs have attained a fragile peace—one that Sahm is hell-bent on destroying. He convinces Young Jun, his best friend and the heir to the Hop Wei, to smuggle opium behind his father’s back. Meanwhile, Mai Ling continues to consolidate power for herself and the Long Zii through back-channeling with Buckley, who’s making assurances that their gang activity in Chinatown won’t get the police’s attention. Also, the Irish mob, led by the eternally swole Dylan Leary, are emboldened to bomb local factories that have hired cheaper Chinese workers. San Francisco is, in short, a complete shit show teeming with violence and racial animus.

If you know your history, Warrior is heading toward the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the only American law that explicitly prohibited immigration into the country for a specific racial group. It’s one of many ugly stains in the country’s long history of racism, and the anti-Chinese sentiment that forms the undercurrent of Warrior has gained even more prescience with the xenophobic treatment of Asian American individuals and communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. When it comes to America’s treatment of its Asian citizens, history is very much repeating itself.

Warrior does not shy away from such atrocities on-screen; injustice is embedded in the show’s DNA. When Bruce Lee pitched the basic idea for his vision of Warrior, about a Chinese martial artist making his way through the American West, he said that studios were reluctant to give the green light out of fear that a show with a nonwhite lead would not find an audience. The premise was then stolen and repurposed for the 1972 ABC series Kung Fu, produced by Warner Bros. Television and starring David Carradine, though the studio has denied any wrongdoing. (Lee did audition for the lead role in Kung Fu shortly before his death, but producers believed that viewers wouldn’t understand his accent.)

Nevertheless, Warrior also pays homage to Lee’s original vision. In Season 1, Sahm and Young Jun spend a stand-alone episode holed up at a Chinese-owned saloon in the middle of nowhere, which eventually leads them to take out a band of racist outlaws. Then, in the second season, another stand-alone sees Sahm enter a Bloodsport-esque tournament on the California-Mexico border, overseen by a Southern baron who comes across like a relative of Leonardo DiCaprio’s slave owner from Django Unchained. In taking these detours from the main action in San Francisco, Warrior makes its world feel real and lived-in—one where new conflicts and characters can be found all across the American West.

Ideally, Warrior would be able to continue that thread with more stand-alone episodes—and, just as important, impressively choreographed fight sequences—in future seasons. But Cinemax’s already-imposed original programming shutdown, which was announced after Warrior was renewed for Season 2, means that the show is effectively cancelled. The only hope, as Shannon Lee has explained in interviews, is for Warrior to find an audience on HBO Max, where the series will be placed after the second season finishes airing on Cinemax.

It would not be unprecedented for Warrior to get a second life on a streamer. We’ve seen it happen with other once-canceled shows like The Expanse, and HBO Max has already revived other WarnerMedia offshoots, including shows from the short-lived DC Universe streaming service (Harley Quinn, Doom Patrol). I’ve already gone to bat for The Expanse—not that a fandom which mobilized to fly a banner over Amazon Studios’ headquarters needed one measly blogger’s support. But Warrior doesn’t appear to have the same level of fanfare, in terms of ratings or an online presence—some of which might come down to, again, a lack of familiarity with Cinemax. (It’s not hard to imagine Warrior faring better on HBO proper.)

Perhaps, like Cobra Kai, which has gained newfound prominence on Netflix, this martial arts show just needs a bigger platform to find an audience. After all, it shouldn’t take much to sell an action enthusiast on Warrior. It would be great if HBO Max righted a longtime wrong of a martial arts legend by finally bringing his vision to life, examined the Chinese immigrant experience that Hollywood has long overlooked, or provided a regrettably rare platform for Asian and Asian American actors in meaningful leading roles. Warrior does all of that, and packs one hell of a punch.

Spread the word