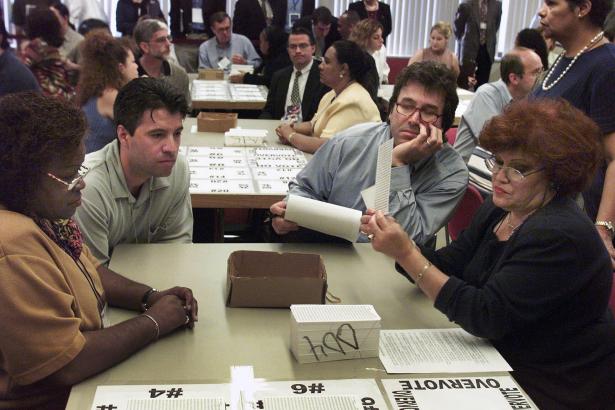

The stormy once-in-a-lifetime Florida recount battle that polarized the nation in 2000 and left the Supreme Court to decide the presidency may soon look like a high school student council election compared with what could be coming after this November’s election.

Imagine not just another Florida, but a dozen Floridas. Not just one set of lawsuits but a vast array of them. And instead of two restrained candidates staying out of sight and leaving the fight to surrogates, a sitting president of the United States unleashing ALL CAPS Twitter blasts from the Oval Office while seeking ways to use the power of his office to intervene.

The possibility of an ugly November — and perhaps even December and January — has emerged more starkly in recent days as President Trump complains that the election will be rigged and Democrats accuse him of trying to make that a self-fulfilling prophesy.

With about 85 days until Nov. 3, lawyers are already in court mounting pre-emptive strikes and preparing for the larger, scorched-earth engagements likely to come. Like the Trump campaign, Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s campaign and its network of Democratic support groups are stocking up on lawyers, and Democrats are gaming out worst-case scenarios, including how to respond if Mr. Trump prematurely declares victory or sends federal officers into the party’s strongholds as an intimidation tactic.

The emerging battle is the latest iteration of the long-running dispute over voting rights, one shaped by the view that higher participation will improve the Democratic Party’s chances. Republicans, under cover of dubious or unfounded claims about widespread fraud, are trying to prevent steps that would make it easier for more people to vote and Democrats are pressing more aggressively than ever to secure ballot access and expand the electorate.

But that clash has been vastly complicated this year by the challenge of holding a national election in the middle of a deadly pandemic, with a greater reliance on mail-in voting that could prolong the counting in a way that turns Election Day into Election Week or Election Month. And the atmosphere has been inflamed by a president who is already using words like “coup,” “fraud” and “corrupt” to delegitimize the vote even before it happens.

The battle is playing out on two tracks: defining the rules about how the voting will take place, and preparing for fights over how the votes should be counted and contesting the outcome.

“The big electoral crisis arises from the prospect of hundreds of thousands of ballots not being counted in decisive states until a week after the election or more,” said Richard H. Pildes, a constitutional scholar at New York University School of Law.

If the candidate who appears ahead on election night ends up losing later on, he said, it will fuel suspicion, conspiracy theories and polarization. “I have no doubt the situation will be explosive,” he said.

Some flash points have already emerged:

-

A long-troubled Postal Service, now run by a Trump megadonor and seemingly overwhelmed by the prospect of delivering tens of millions more votes cast by mail with an administration resistant to providing substantial new funding.

-

Concern among Democrats that Mr. Trump or Attorney General William P. Barr could use their bully pulpits to raise loud enough alarms about voter fraud to lead sympathetic state and local officials to slow or block adverse results.

-

Fights over whether mailed ballots should be counted if received by Election Day or simply postmarked by Election Day, not to mention what to do if the post office does not postmark them at all.

-

Fights over the use of drop boxes to return ballots and the number of polling places for in-person voting amid the risk of disease.

-

Fights over whether witnesses should still be required for absentee votes in a socially distant moment and what to do if signatures do not match those on file.

Already, by Mr. Pildes’s count, party organizations, campaigns and interest groups have filed 160 lawsuits across the country trying to shape the rules of the election. About 40 have been filed in 17 states by Mr. Trump’s campaign and the Republican National Committee, some in response to Democratic lawsuits, as part of an expansive $20 million litigation campaign against policies making it easier to vote on the grounds that they could lead to fraud.

“See you in Court!” Mr. Trump tweeted a few days ago to Nevada, which just passed universal mail-in balloting legislation, under which the state sends a mail-in ballot to every registered voter.

In an illegal late night coup, Nevada’s clubhouse Governor made it impossible for Republicans to win the state. Post Office could never handle the Traffic of Mail-In Votes without preparation. Using Covid to steal the state. See you in Court! https://t.co/cNSPINgCY7

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 3, 2020

“They are just really efforts to throw tacks in front of the tires to make it so states can’t run their elections this time,” said Michael Waldman, the president of the Brennan Center for Justice and a former aide to President Bill Clinton.

Democrats and their allies, led by Marc E. Elias, the general counsel of the Democratic National Committee, are seeking to expand voting options, particularly through mail-in voting. They have active litigation in numerous battleground states, pursuing relief on deadlines, signature and witness requirements, among others.

Republicans said their own court efforts were aimed at preventing Democrats from changing the rules in the middle of the game.

“People are viewing it as an attack on vote-by-mail,” said Justin Riemer, the chief counsel for the Republican National Committee. But in fact, he said, “it’s by and large protecting the safeguards that are in place.”

Mr. Trump, who also made unfounded claims about fraud in the 2016 election even though he won, has signaled that he will not hesitate to go back to court after Election Day if he does not like the result. Unlike in 2000, when the Justice Department largely stayed on the sidelines, Democrats worry that Mr. Barr will intervene with civil suits, investigations or public statements, casting doubt on the result if Mr. Trump appears to lose. And some Democrats say they are not sure how Mr. Trump would respond, with the presidency on the line, to a court ruling against him.

Some Democrats even express fear that Mr. Trump would send federal agents into the streets as he did in recent weeks in Portland, Ore. Democrats have game-planned situations in which Mr. Trump deploys immigration officers into Hispanic neighborhoods to intimidate citizens shortly before the election and suppress turnout.

“It is very, very much a concern,” said Alex Padilla, the secretary of state of California.

Mr. Trump’s advisers dismiss such talk as overheated partisan messaging. Justin Clark, the president’s deputy campaign manager, said states like California and Nevada trying to expand mail-in voting on the fly were the ones setting the stage for a chaotic election.

“Rushing to implement universal vote-by-mail leads to delays in counts, delays in results and uncertainty about who won an election,” he said.

It took six weeks for the New York authorities to determine the winners of two House Democratic congressional primaries as they struggled with 10 times the normal number of absentee ballots, a case study in the potential for a lengthy count in the fall even if not an example of fraud as Mr. Trump has falsely claimed.

Mr. Clark is one of the party’s top warriors on election fraud fights. In a recording from 2019, he told fellow Republicans: “Traditionally, it’s always been Republicans suppressing votes in places. Let’s start protecting our voters.”

Republicans, he said, should be more aggressive. “Let’s start playing offense a little bit,” he said then. “That’s what you’re going to see in 2020. It’s going to be a much bigger program, a much more aggressive program, a much better-funded program.”

He later said he was referring to false accusations made against Republicans. A federal judge in 2018 lifted a consent decree in place since 1982 that barred the Republican National Committee from certain so-called ballot security efforts.

Asked about those comments, Mr. Clark said: “Democrats have always accused Republicans of voter suppression. The fact of the matter is all Democrats have done this year is pushed crazy voting laws.”

The Trump team has also tried to halt another pillar of absentee voting — the drop box. In 2018 in Colorado, one of five states that already votes nearly entirely by mail, 75 percent of ballots were returned through a drop box or at a polling place. In Pennsylvania, the Trump campaign sued against expanding the use of drop boxes, an action that has concerned election officials across the country.

Jena Griswold, the secretary of state of Colorado, said the president’s attacks on the Postal Service and his refusal to devote enough resources to fix its problems showed his disingenuous motives.

“You do all that and then you attack drop boxes, the alternative to voting safely, it’s a pattern of voter suppression,” she said. “It’s a pattern of voter suppression and I just think it’s really reprehensible.”

Others are looking to head off disqualifying ballots over procedural issues like postmarks and the date of receipt. “Voting shouldn’t be a game of gotcha,” said Ann Jacobs, the chairwoman of the Wisconsin Elections Commission.

The Help America Vote Act, passed on large bipartisan votes in 2002 in response to the Florida recount, was meant to help states upgrade and standardize voting procedures. But it gives the attorney general the power to file civil suits to enforce its provisions and some critics said Mr. Barr could use that to step in.

Some Democrats said they were less worried about direct intervention by Mr. Trump or Mr. Barr, but said they could use their positions to prod sympathetic state and local officials to block votes while fostering a narrative undercutting the credibility of a vote count going against the president.

“The president has very little, if any, power with how elections are conducted,” said Mr. Elias, the Democratic lawyer. “Trump’s power is that he has no shame and that shamelessness has infected his entire political party.”

He added, “You cannot imagine the party of George Bush or of John McCain or Mitt Romney or even Reince Priebus saying out loud the things Donald Trump screams out loud on Twitter, in the Oval Office and the Rose Garden on daily and weekly basis.”

With the prospect of an extended and messy count lasting long past Election Day, new attention is focusing on deadlines set by federal law. Under the so-called safe harbor provision, states have until Dec. 8 to resolve disputes over the results, meaning only five weeks — the same deadline that led to the Florida recount being called off in 2000 with George W. Bush in the lead.

Senator Marco Rubio, Republican of Florida, warning about “a nightmare scenario for our nation,” introduced legislation on Thursday extending that deadline to Jan. 1, giving states three-and-a-half more weeks to count. The Electoral College would then meet Jan. 2 instead of Dec. 14, still in time to provide their results to Congress to ratify the outcome on Jan. 6 as scheduled.

In the end, it may depend on how close the count really is.

If “it’s clear one candidate or the other has a clear majority in the Electoral College, then I don’t think there’s much Trump could do if he’s the loser except to complain,” said Trevor Potter, the president of the Campaign Legal Center and former chairman of the Federal Election Commission. “But if it’s close, then I think there is the potential for lots of mischief.”

Peter Baker is the chief White House correspondent for The New York Times, responsible for covering President Trump, the fourth president he has covered. He covered President Obama for The Times and Bill Clinton and George W. Bush for The Washington Post.

Mr. Baker is the author of five books, most recently "Impeachment: An American History" (Modern Library, 2018) with Jon Meacham, Timothy Naftali and Jeffrey A. Engel. He also wrote “Obama: The Call of History” (New York Times/Callaway, 2017), a finalist for an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work; “Days of Fire: Bush and Cheney in the White House” (Doubleday, 2013), which was named one of the five Best Non-Fiction Books of 2013 by The New York Times Book Review; “The Breach: Inside the Impeachment and Trial of William Jefferson Clinton” (Scribner, 2000), a New York Times bestseller; and, with Ms. Glasser, “Kremlin Rising: Vladimir Putin’s Russia and the End of Revolution” (Scribner, 2005), named one of the Best Books of 2005 by The Washington Post Book World. He will publish his sixth book in September 2020, “The Man Who Ran Washington: The Life and Times of James A. Baker III,” co-authored with Ms. Glasser and published by Doubleday.

Mr. Baker has won all three major awards devoted to White House reporting: the Gerald R. Ford Prize for Distinguished Coverage of the Presidency (twice), the Aldo Beckman Memorial Award (twice) and the Merriman Smith Memorial Award. Mr. Baker is also a political analyst for MSNBC and a regular panelist on PBS’s “Washington Week.”

Nick Corasaniti is a domestic correspondent covering national politics for The New York Times.

Mr. Corasaniti was one of the lead reporters covering Donald Trump's campaign for president in 2016 and has been covering presidential, congressional, gubernatorial and mayoral campaigns for the Times since 2011. A New Jersey native, Mr. Corasaniti was most recently the Times's correspondent from the Garden State, covering the politics, policy, people, trains, beaches and eccentricities that give the Garden State its charm.

Michael S. Schmidt is a Washington correspondent for The Times who covers national security and federal investigations. He was part of two teams that won Pulitzer Prizes in 2018 — one for reporting on workplace sexual harassment issues and the other for coverage of President Donald Trump and his campaign’s ties to Russia.

For the past year, Michael’s coverage has focused on Robert S. Mueller III's investigation into Mr. Trump's campaign and whether the president obstructed justice.

Maggie Haberman is a White House correspondent who joined The Times in 2015 and was part of a team that won a Pulitzer Prize in 2018 for reporting on Donald Trump’s advisers and their connections to Russia.

Before joining The Times as a campaign correspondent, Ms. Haberman worked as a political reporter at Politico, from 2010 to 2015. She previously worked at other publications, including The New York Post and The New York Daily News.

She was a finalist for the Mirror Awards, with Glenn Thrush, for the 2014 profile "What Is Hillary Clinton Afraid Of?

Spread the word