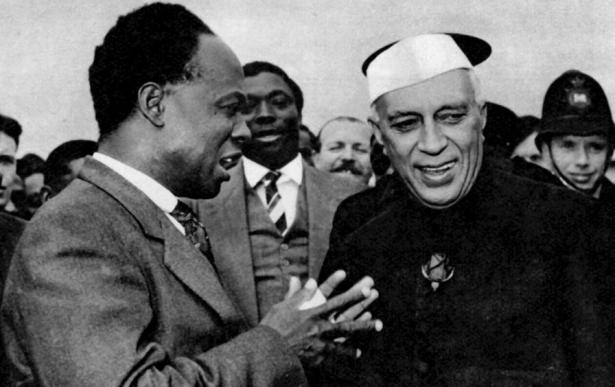

If you were asked, in March 1957, to pick a capital for the black world, there would have been only one answer: Accra, Ghana. It was there, at the Old Polo Grounds, that the first sub-Saharan African colony to gain independence in the post–World War II era celebrated its freedom. “At long last, the battle has ended,” announced Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first prime minister. As the new national anthem played, he wept.

Nkrumah wasn’t the only one. Accra bristled with black leaders from around the world. Martin Luther King Jr. and A. Philip Randolph from the United States; Julius Nyerere, the future first president of Tanzania; the St. Lucian economist W. Arthur Lewis and the Trinidadian historian C.L.R. James—virtually the whole A-list was there. Louis Armstrong and W.E.B. Du Bois were missing, but Armstrong’s wife, Lucille Wilson, was on hand to extend good wishes, and Du Bois would eventually move to Ghana and spend his last years in Accra.

Richard Nixon was there, too, dispatched by President Dwight Eisenhower to represent the United States. “How does it feel to be free?” he asked a black guest at dinner, according to a frequently told story. “I don’t know,” came the response. “I’m from Alabama.”

That exchange, though probably apocryphal, is nevertheless telling. In 1957, when it came to liberation, Ghana was ahead of the United States. And the country’s independence “opened wide the floodgates of African freedom,” Nkrumah wrote. By the end of 1960, 17 more former colonies had joined the United Nations as independent states; five years later, there were 33. While the US government dithered about whether African Americans living in the South should be able to vote and attend state universities, black people from Kingston to Nairobi were flying new flags and taking seats in their national parliaments.

It was an exciting time, but it was also a dangerous one. Both the excitement and danger were on display in the Republic of the Congo in 1960. Under Belgian rule, the Congo had endured some of the most murderous governance in colonialism’s bloody history, and the new prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, didn’t mince words: At the new republic’s flag-raising, he gave a defiant speech castigating Belgium. The free Congo would “show the world what the black man can do when he works in freedom,” he promised.

That freedom, however, was at risk almost from the start. Less than two weeks after his speech, Belgian officials prodded a group of rebels led by Moïse Tshombe in the resource-rich southern province of Katanga to declare independence. European mining companies backed the rebels, expecting to secure better deals from Tshombe than from the anti-imperialist Lumumba. The Belgian government, thinking along similar lines, dispatched an assassin to kill Lumumba; ready to pitch in, the CIA sent two assassins as well. Before any of the killers reached their mark, Tshombe’s men got hold of Lumumba and tortured and executed him. They buried the body but later dug it up, chopped it into bits, and dissolved it in acid so that no one would be able to visit his grave.

Nkrumah, who had regarded Lumumba as a comrade, looked on in horror. How meaningful was independence when foreign corporations and governments could foment rebellions and have elected leaders murdered with impunity? What if the newly freed states were individually too weak to defend themselves against threats from abroad? Nkrumah had called on the newly liberated African states to work together to repel imperialism. Lumumba’s murder was a reminder that unless they did so, “our independence,” as Nkrumah put it, “is meaningless.”

The effort to protect national independence is the subject of Adom Getachew’s extraordinary new book, Worldmaking After Empire. Getachew, a political theorist at the University of Chicago, tells the story of a group of leading black anti-imperialists who sought to secure the freedom of their postcolonial states by turning to international relations. Rather than classify these anticolonial activists exclusively as nationalists, Getachew argues that they had to become internationalists if they were to realize their nations’ independence. The global hierarchy that put people of color on the bottom and whites on top could be overturned only through concerted and coordinated effort on a worldwide scale. It would require “a radical rupture” and “a reconstitution of the international order” to address deep-seated global inequalities. Recognizing their global ambitions, Getachew calls these black anti-imperialists “worldmakers.” In thinking beyond the nation-state, she argues, they have much to teach us today.

At first, the 20th century looked as if it might be the century of the nation-state. World War I ended with the breakup of the German, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian empires, and with that came much talk of self-determination, particularly from Woodrow Wilson, who presided over the postwar settlement. “National aspirations must be respected,” he insisted. “Peoples may now be dominated and governed only by their own consent.” It was on this principle that he proposed a world governed by a league of nations rather than by the empires that had ruled for centuries, and it was on this principle that 42 countries signed on to found such a league.

Yet Wilson’s commitment to self-determination came with an important caveat. He had grown up in the antebellum South—his father wrote a pamphlet titled “Mutual Relations of Masters and Slaves as Taught in the Bible”—and he’d inherited the view that certain people weren’t ready to rule themselves. During Wilson’s presidency, the incendiary racist film The Birth of a Nation appeared. It was written by a friend of his and quoted Wilson’s writings. When it seemed that censors concerned about its adulation of the Ku Klux Klan might prevent it from playing, Wilson set the tone by screening it at the White House. The president, W.E.B. Du Bois observed in what was surely an understatement, “did not seem to understand [the] world-wide problems of race.”

That failure of understanding went far beyond Wilson. For all the state-building in postwar Europe, more than a third of the land on the planet remained colonized. The League of Nations didn’t contest this. Rather, it had its own role in preserving what Getachew calls a worldwide “structure of racial hierarchy.” Though the league upheld the independence of the newly established European nations like Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia, when it came to the lands outside Europe, the league’s view of self-determination proved far more conditional. Instead of liberating the nonwhite domains of World War I’s vanquished empires, the league converted them into a set of quasi-colonies known as mandates, to be governed by outsiders on the understanding that such places weren’t fit to rule themselves. Even the three black countries that made it into the league as independent states—Haiti, Ethiopia, and Liberia—faced accusations of unfitness. While the league’s white leaders turned a blind eye to forced labor in Europe’s colonies, they obsessed over it in Liberia and Ethiopia and openly considered “mandation”—the conversion of sovereign black countries into mandates—as a remedy. Meanwhile, the United States occupied Haiti from 1915 to 1934 in order to maintain “stability.” As Getachew notes, to the white powers of the world, the very idea of a self-governing black nation appeared “as a contradiction in terms.”

Nkrumah, in London at the time, expressed his profound sense of anger at the league’s betrayal of an African member. “It was almost as if the whole of London had suddenly declared war on me personally,” he recalled. “For the next few minutes I could do nothing but glare at each impassive face, wondering if those people could possibly realize the wickedness of colonialism.”

Nkrumah took pleasure in that fact, but having watched how the great powers treated Ethiopia, Liberia, and Haiti, he doubted it would suffice without the new nations of Africa tackling white imperialism head-on. In his view, the situation required not a change-bearing wind but a “raging hurricane against which the old order cannot stand.” That old order was more than colonialism; it was the whole system of international hierarchy that upheld the rule of white over black.

Nkrumah and his cohort of anticolonial activists won their fame fighting for the independence of their own countries, but they were nonetheless serious in their border-transcending ambitions. For Getachew, their internationalism helps clarify an underexamined aspect of decolonization. It can’t be understood as just an “empire-to-nation narrative”; it also has to be understood as a much more wide-ranging struggle over what kind of international order the world should have.

In Nkrumah’s eyes, the problem with the new nation-states was that they weren’t strong enough to protect themselves. He looked at independent Africa and saw a balkanized set of “small, weak states.” A united Africa, he argued, could pool its resources, plan its economy, and thwart the sort of divide-and-rule tactics that latter-day imperialists used when they backed the Katangan rebels against Lumumba’s regime in the Congo. Africa could be like China, Nkrumah believed, poor but large enough to be formidable.

Nkrumah also had another model in mind: the United States. Just as 13 British colonies had joined together in the 18th century to form the United States of America, Nkrumah sought to create a Union of African States from the continent’s former colonies. Getachew notes the irony of Nkrumah, a staunch critic of US foreign policy, emulating the country’s creation, and she wonders whether the United States—a white settler nation carved out of Native American land—was the most promising model for African liberation. Nevertheless, Nkrumah forged ahead in hot pursuit of a federation. Under his influence, the Ghanaian Constitution contained an astonishing clause allowing the country to fully surrender its sovereignty to a future African Union. Guinea did the same, and the two countries issued a joint communiqué explaining that they’d taken “inspiration from the thirteen American colonies.” Mali joined the provisional union as well, and Lumumba, before his murder, traveled to Accra to negotiate the entry of the Congo.

The black intellectual world was a connected one, with ideas taking wing across the Atlantic, and while Nkrumah sought to organize a postcolonial union in Africa, the Trinidadian historian and political leader Eric Williams pursued it in the Caribbean. There, he hoped that regional unification would allow the island states to fend off US meddling. “Two hundred years ago we were sugar plantations,” he said. “Today we are naval bases”—a reference to the US outposts that dotted the region, perforating the sovereignty of Caribbean nations. Williams sought to turn the existing British-designed West Indies Federation into a stronger, centrally controlled union of independent Caribbean states. Without this, he feared, the West Indies would devolve into a set of banana republics, riddled with US bases and run by puppet governments.

What might these unions have looked like? In Nkrumah’s version, the African Union would have a single currency and market, a single military and foreign policy, and a central government with the power to tax. Getachew shows that unification along these lines had a surprising amount of support among Africa’s leaders. Even Nkrumah’s adversary in the unification debate, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, who favored a looser federation, agreed that “the ultimate destiny of this continent lies in political union.

But Selassie and his allies also worried about handing over too much power to a central body. Nigeria’s leader Nnamdi Azikiwe spoke of “deep-seated fears” that an overarching government would mean the loss of the independence they had all fought so hard to attain. Nkrumah’s opponents worried that the smaller states might be steamrollered by the larger ones in a union, and they had cause for concern. The first president of independent Togo, Sylvanus Olympio, called Nkrumah a “black imperialist”; shortly after, assassins tried to kill Olympio, and it was clear that Ghana was involved. Nkrumah’s covert meddling in other African countries made it hard to build trust for his proposal. Instead, African leaders opted for Selassie’s solution—to establish the Organization of African Unity, a treaty organization.

Williams wasn’t mired in such machinations, but his efforts were also thwarted when Jamaica pulled out of his federation. After this “Jexit,” the other islands went their own way, and Trinidad and Tobago gained independence as a separate nation, with a disappointed Williams as its first prime minister.

Nkrumah and Williams feared for the fate of weak nations in a world dominated by great powers, and subsequent events proved them right. The CIA had a “program to neutralize Dr. Williams,” Getachew writes, though what that entailed remains unclear. Nkrumah was ousted by his own military in 1966. He claimed the rebels were “egged on by their neo-colonialist masters,” and the CIA indeed appears to have coordinated with them. Then–CIA officer John Stockwell wrote that “inside CIA headquarters, the Accra station was given full, if unofficial credit” for the coup.

Whatever the agency’s role, Nkrumah’s ouster was a “fortuitous windfall” for the United States, as Robert Komer, one of President Lyndon Johnson’s advisers, put it. In a confidential memo for Johnson, Komer added that Nkrumah had done “more to undermine our interests than any other black African.” The new Ghanaian regime, by contrast, was “almost pathetically pro-Western.”

Within a decade of Ghanaian independence, the idea of regional union was no longer in the realm of immediate possibility. Black countries would now have to face a white-dominated world order as individual nation-states and without the concentrated power and leverage of operating in tandem. National sovereignty, which for worldmakers had been merely a first step, was now the final form that black liberation would take, and there was no China-size black country capable of dictating terms to the world’s great powers. Getachew laments this, as did Williams. After the West Indies Federation’s collapse in May 1962, Williams summed up the worrisome plight of Trinidad and Tobago as being “a small country in a big world.”

Nkrumah and Williams had hoped to lash nation-states together into larger political bodies. But this wasn’t the only option the postcolonial worldmakers considered. They also understood that if they could nationalize the raw materials mined, tapped, or grown in poorer countries, they could demand new rules for the world system. The model here wasn’t a political union but a cartel—or as Tanzania’s President Julius Nyerere put it, “a trade union for the poor.” Getachew devotes a chapter to this vision and shows just how far the worldmakers got in their efforts to reshape international relations.

One raw material seemed especially promising: oil. The world oil market had long been dominated by European and US corporations. But in the 1970s, oil exporters coordinated and reversed the terms of trade, claiming greater shares of revenue and dramatically hiking prices in the process. From 1970 to 1974, the posted price of a barrel of Dubai light crude skyrocketed from $1.80 to $13. In the oil-importing West, this was an oil crisis. Exporting countries had a different name for it; they called it an “oil revolution.”

The oil revolution emboldened a new generation of worldmakers across the Global South. Through it, they saw a way to address a fundamental injustice in the world economy. “Why does a man growing cocoa earn one tenth of the wage of a man making steel ingots?” asked the St. Lucian economist W. Arthur Lewis. Perhaps, through collective action, these countries could not only raise oil revenues but also set new ground rules to reverse the unfair terms of global trade and overturn an economic hierarchy of nations that ran parallel to the political one. In 1974, they passed a resolution in the United Nations General Assembly announcing a New International Economic Order, one that was intended to redirect resources from rich to poor countries and sharply curtail the power of multinational corporations.

The World Bank’s then–policy director, Mahbub ul Haq, compared the New International Economic Order to the United States’ New Deal but on a global scale. Carrying it out would require new institutions of economic governance to tax the rich nations and direct the revenues to the poorer ones. Getachew notes that such an arrangement would have done nothing to secure fairer economies within the countries of the Global South, but she nevertheless recognizes it as a redistributive program of major significance. The architects of the NIEO also grasped its significance: They declared it to be, in the words of Algerian leader Houari Boumédiène, a “decisive turning-point in the course of international relations.”

But if the NIEO was such a turning point, it would prove to be one (as G.M. Trevelyan said of Europe’s 1848 revolutions) at which history failed to turn. Backstopped by the oil revolution, the NIEO seemed at first to be a serious challenge to the world system. Yet its opponents soon realized they could hold out against it, and ultimately no coordinated campaign emerged from the Global South to force them to agree to the NIEO’s terms.

Part of the problem was a lack of unity within the Global South. The oil revolution buoyed hopes, but it also drove a wedge between the oil-exporting countries and the many “NoPEC” nations, for whom rising oil prices spelled economic catastrophe. As nice as it was to see Europe and the United States sweat in the face of price hikes, the hardest-hit countries were the poorest ones. Ghanaian government economists calculated that oil, ballooning in cost, would soon account for more than a fifth of Ghana’s total import spending. Solidarity was hard to maintain when oil controls propelled some countries of the Global South into opulence and drove others into debt.

Getachew acknowledges this, but she argues instead that the true cause of the NIEO’s end was a “strategic and concerted effort” by the rich countries to bring it down. They certainly tried: As the historians Daniel Sargent and Chris Dietrich have shown using declassified documents, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger directed a considerable amount of energy toward breaking the NIEO. “Our basic strategy,” he explained, “must be to hold the industrialized powers behind us and to split the Third World.” He pressured the rich countries to stand firm in the face of redistributionist demands. To divide his adversaries, he requested hundreds of millions of dollars in aid, designing the aid packages to pry their recipients away from the NIEO coalition. Meanwhile, his colleague Daniel Patrick Moynihan went on the offensive in the United Nations, accusing leaders in the Global South of human rights violations. Kissinger hoped to introduce enough “ambiguities” into the situation to “fuzz it up.” This was, Getachew writes, a “counterrevolution against the aspiration for an egalitarian global economy.”

Whether because of Kissinger’s schemes or the hard realities of the oil economy, the NIEO collapsed. Tanzania’s Nyerere, whom Getachew deems the “center of gravity” in African worldmaking after Nkrumah’s ouster, was one of the NIEO’s chief backers. Yet by 1977 even he could see that a more egalitarian world order was unlikely to take root. His country was one of the NoPEC nations suffering the contractions wrought by rising oil prices. With those contractions came debt, and with debt came the International Monetary Fund and its loans, replete with strings attached. Nyerere stepped down as president in 1985. He did so just before his government adopted a punishing round of IMF-mandated austerity measures—the price of borrowing from European creditors.

Tanzania’s fall was all too typical. The debt crisis and death of the NIEO closed off any further opportunities for the postcolonial worldmakers in the 20th century. It wasn’t only that they lost power; it was also that the very arena of contestation—international institutions, particularly those clustered around the UN—now mattered less.

The economies of the former colonies have made great strides over the past few decades. In sub-Saharan Africa, average incomes have risen over tenfold and life spans have increased by more than 20 years since 1960. Yet such growth is barely visible when placed alongside that of a rich country like the United States, which saw its economy grow twentyfold in the same period and boasts a per capita GDP almost 40 times that of sub-Saharan Africa. The redistributive equality that the NIEO sought has receded from view and, with it, the possibility that the black world might dictate terms to international society.

Visionaries like Nkrumah and Williams didn’t, in the end, remake the world through regional federations. Nor did their successors through the NIEO. Nevertheless, Getachew is struck by the ambition of these plans. Not only did these worldmakers seek justice on a global scale; they also proposed a collaboration in the Global South so thoroughgoing that it challenged the operating notion that the fundamental units of international society should be nation-states. Remarkably, such ideas had enough momentum to panic governments in the Global North.

Today, we inhabit a world defined by the failure of this new order to emerge. The decades since the NIEO’s collapse have seen a “striking return to and defense of a hierarchical international order” under the unilateral power of the United States, Getachew writes. The measure of this power is not just that the United States has successfully defied international norms but also that the very idea of an egalitarian world order—once a serious historical possibility—now seems to many an absurd fantasy.

Getachew’s book, however, hopes to revive this neglected history in order to show that it was more than a “dead end”; it can serve as a “staging ground for reimagining the future.” Getachew couldn’t have picked a better time to publish a book excavating a more egalitarian internationalism from the past. Brexit and Trumpism have shown that the old powers can no longer lead international institutions. And the drastic heating of the planet has shown how ineffectual nation-states have been at tackling problems of planetary scope. The question now is what a future world order will look like. Will regional federations grow or, as we are seeing in the European Union, threaten to break apart? Will the nations of the Global South join together? Will a powerful international body arise to stave off climate change?

Getachew doesn’t offer solutions, nor does she propose that the decades-old ideas of the anti-imperial worldmakers be revived intact; her book, after all, is primarily a work of history. But she does ask us to return to an earlier moment of bold creativity, when an egalitarian world order was imaginable, and when thinkers from the Global South set to work to bring it about. We could use more of that.

Daniel Immerwahr is an associate professor of history at Northwestern University. He is the author of Thinking Small: The United States and the Lure of Community Development and How to Hide an Empire.

Copyright c 2019 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission. Distributed by PARS International Corp.

Please support progressive journalism. Get a digital subscription to The Nation for just $9.50!

SUPPORT PROGRESSIVE JOURNALISM If you like this article, please give today to help fund The Nation’s work.

Spread the word