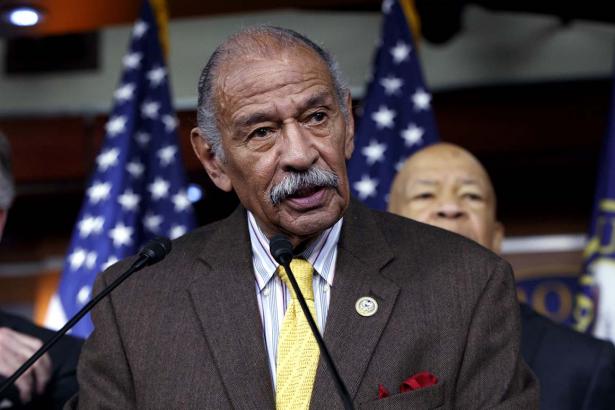

Former Rep. John Conyers, the longest-serving African-American congressman in American history, died Sunday.

The Detroit Democrat, who served from 1965 until a sexual harassment scandal led to his resignation, was 90.

“Former Representative John Conyers Jr. of Michigan has died at 90,” the journalist Yamiche Alcindor tweeted Sunday afternoon. “I just spoke with his son, John Conyers III who told me his father passed away in his sleep. Rep. Conyers represented the Detroit area for more than five decades before resigning in 2017.”

Conyers represented Detroit through some of the most difficult years in its history, a time in which the woes of the American auto industry caused the city to go into a steep economic decline. But along with John Dingell Jr., who died earlier this year at the age of 92 having served 59+ years in Congress, he gave Michigan seniority — and two powerful voices on Capitol Hill.

Conyers served during his career as chairman of the House Oversight Committee and later the House Judiciary Committee. He was also one of the co-founders of the Congressional Black Caucus in 1969.

Rep. Rashida Tlaib, who now holds Conyers’ old seat, tweeted Sunday: “Our Congressman forever, John Conyers, Jr. He never once wavered in fighting for jobs, justice and peace. We always knew where he stood on issues of equality and civil rights in the fight for the people. Thank you Congressman Conyers for fighting for us for over 50 years.”

Our Congressman forever, John Conyers, Jr. He never once wavered in fighting for jobs, justice and peace. We always knew where he stood on issues of equality and civil rights in the fight for the people. Thank you Congressman Conyers for fighting for us for over 50 years.

— Rashida Tlaib (@RashidaTlaib) October 27, 2019

John James Conyers Jr. was born in Highland Park, Mich., on May 16, 1929, and grew up in Detroit. He attended Wayne State University, where he received both his undergraduate and law degrees, and also served in the U.S. Army during the Korean War as part of a unit of African-American combat engineers. He subsequently became a civil rights activist, taking part in voting rights efforts in Selma, Ala., in 1963, and served as an aide to Dingell.

The next year, he made his first run for Congress. Michigan’s congressional districts had been redrawn after a 1962 Supreme Court decision, Baker v. Carr, which made it unconstitutional to draw districts in a way that under-represents minority voters. Conyers prevailed in a battle for an open seat.

“He vowed to represent people who are caught between the VIP class of Negro life and the lower class which is dependent on relief, low-income housing, and welfare,“ Ebony magazine wrote in a 1965 profile.

One of Conyers’ early supporters in his 1964 campaign was the activist Rosa Parks, whose 1955 arrest had launched the bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala. Unable to find work, she had long since moved to Detroit.

“If it wasn’t for Rosa Parks, I never would have gotten elected,” he said, according to Jeanne Theoharis’ “The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks.”

Conyers hired Parks after the election, and though he faced complaints about employing her, she remained on his staff until retiring in 1988.

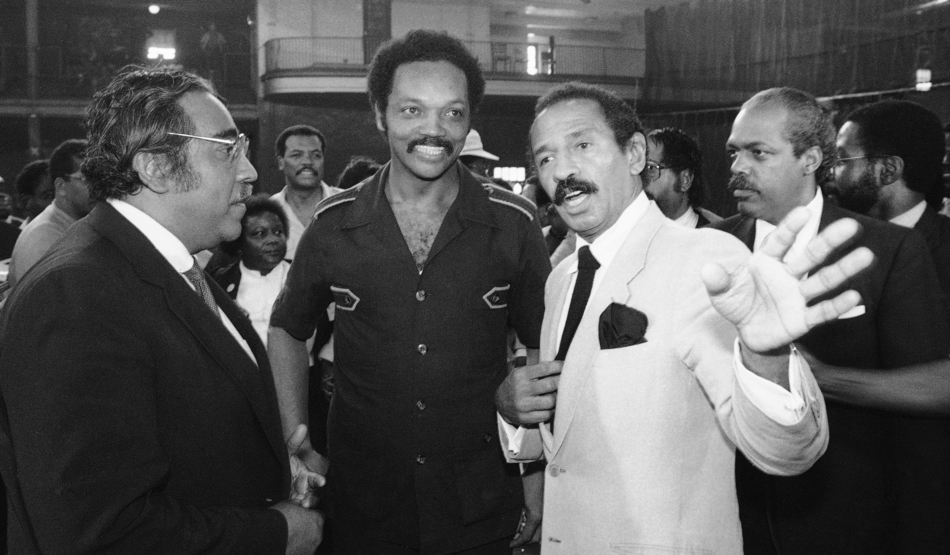

During a lethal riot in Detroit in July 1967, Rep. John Conyers uses a bullhorn to urge residents to return to their homes. | AP Photo

Conyers said his father’s work with the United Auto Workers inspired his activism.

“I was always drawn to the struggle because my dad was a labor organizer for the UAW,” he said in a 1988 interview.

“Well, he had been in the labor movement at Chrysler, in the auto plants, even before the UAW, where it was illegal to be in unions, and you had to wear your button on your underwear under your shirt, where you would get beat up, and thrown out, you’d get beat up before you got fired, for trying to form a union, so I came up in that kind of environment. … He retired as an international representative for UAW. So I always had a political view, and the civil rights movement, of course, was electrifying.”

The Detroit Democrat was consistently a progressive voice and would always, for better or worse, be identified with progressive causes. Frequently, he was a thorn in the side of Republican presidents. In 1971, he was listed as one of 20 names in an enemies list drawn up by the Nixon White House, alongside such notables as the actor Paul Newman and journalist Daniel Schorr. (A year later, he introduced a resolution calling for Nixon to be removed from office for his handling of the Vietnam War.)

But he also attacked fellow Democrats at times, once calling President Jimmy Carter “hopeless” and “demented.” In 2010, Conyers faced blowback from President Barack Obama, who didn’t appreciate his policy criticism. At least some members of the Black Caucus sided with Conyers.

“Conyers has been in Congress longer than Barack Obama could spell,” said one strategist. “If he’s making a complaint, it’s a shot across the bow, and you might want to pay attention to that.”

Through his career, he fervently supported such liberal causes as gun control, anti-poverty programs and universal health care. He held hearings to spotlight police misconduct and also supported legislation urging a study of the possibility of offering reparations to the descendants of slaves.

From right, Rep. John Conyers, the Rev Jesse Jackson and Rep. Charlie Rangel (D-N.Y.) confer at a congressional hearing on police brutality in September 1983. | Mario Cabrera/AP Photo

“Over 4 million Africans and their descendants were enslaved in the United States and its colonies from 1619 to 1865, and as a result, the United States was able to begin its grand place as the most prosperous country in the free world,” he said.

In a 2013 interview, he explained how his service in the Korean War had led him to be a strong foe of most of America’s military conflicts. "I'm sure these are views that many will disagree with, but many of these wars were unnecessary," Conyers said.

Days after the 1968 assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Conyers introduced a resolution calling for a national holiday in his name. It took 15 years for that legislative battle to be won, but Conyers persisted. “He single-handledly fought for a King holiday,” the Rev. Jesse Jackson tweeted Sunday. “He led the ground work. He is the reason for the #DrKing holiday.“

Conyers easily won reelection every two years, though he did fail in two attempts to become mayor of Detroit in 1989 and 1993. He was relatively unscathed when his wife, Monica, pleaded guilty to a conspiracy to commit bribery in 2009.

In 2017, reports surfaced that Conyers had settled a sexual harassment lawsuit with a staffer a few years earlier. Additional reports of misconduct allegations came out leading to pressure for Conyers to step down, which he did in December 2017.

“I am retiring today,” he said on Dec. 5, 2017. “And I want everyone to know how much I appreciate the support — the incredible, undiminished support I’ve received across the years from my supporters, not only in my district but across the country as well.”

Some were greatly upset by his departure, others thought it was overdue, but there was no doubt he had made his mark on the institution of Congress.

“It is an ignoble and overdue end to what has been, by any measure, a momentous public life,” POLITICO’s Zack Stanton wrote at the time. “Conyers’ service in Congress has spanned 10 presidencies and 52 years — he’s been in the House for more than one-fifth of the entire existence of the U.S. Congress. In 1964, he went to Jim Crow Mississippi during Freedom Summer and offered legal representation to black voting-rights activists; one year later, he supported the Voting Rights Act as a member of the House of Representatives. He was the only congressman ever endorsed by Martin Luther King Jr.”

Senior editor David Cohen joined POLITICO in 2010 after 25 years in the news business, including extended stints at The Philadelphia Inquirer, Nando.net (now McClatchy Interactive) and The Record of Hackensack (N.J.).

Though he has spent most of his career as an editor, he is the author of "Rugged and Enduring: The Eagles, The Browns and 5 Years of Football,” published in 2001.

Cohen graduated from Northwestern University. A longtime resident of the Philadelphia area, he and his family now reside near D.C.

Spread the word