It’s shocking, simply shocking, that the American people have forgotten the name of Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts. From 1914 to 1964, the brilliant inventor trotted out a series of groundbreaking devices, among them an automatic stamp-licker, a self-operating napkin, and a spoon for fishing stubborn olives out of the bottoms of tall jars. Granted, the devices were usually a little bulky—the stamp-licker required a hat rack, a bucket of water, a live dog, and an umbrella—but that was just another part of their charm.

It’s likely that you’ve never heard of the esteemed Professor Butts, but the name of his creator, Rube Goldberg, should ring a bell. Goldberg’s cartoons—the subject of an exhibition opening October 12th at the National Museum of American Jewish History (NMAJH) in Philadelphia—usually featured hare-brained contraptions designed to complete simple tasks in the most difficult ways imaginable. They appeared in American newspapers for most of the first half of the 20th century, and today, they live on in endless homages, spin-offs, and rip-offs: board games, Simpsons gags, indie music videos, horror franchises, and Sesame Street cutaways.

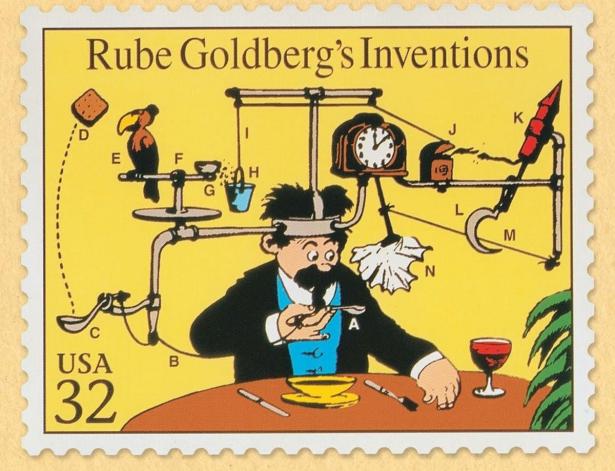

Since 1931, Goldberg’s name has appeared in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary of the English Language, meaning “accomplishing by complex means what seemingly could be done simply”; it’s also been affixed to prestigious awards, engineering contests, and postage stamps. The former Librarian of Congress Daniel Boorstin summed up Goldberg’s enormous appeal like so: “He focuses ingeniously and devastatingly on those peculiar follies and hypocrisies of daily life from which spring the wonderful American standard of living and the American genius for technology.”

How appropriate that he was born on the Fourth of July. In 1883, the year Goldberg came into the world, the Wright Brothers hadn’t yet slipped the surly bonds of earth, and Henry Ford was a humble farmer who liked to tinker with engines in his spare time. In the following decades, America would reinvent itself as the world’s preeminent technological superpower, and Goldberg would become the chief chronicler—and affectionate satirist—of his country’s mechanical misadventures.

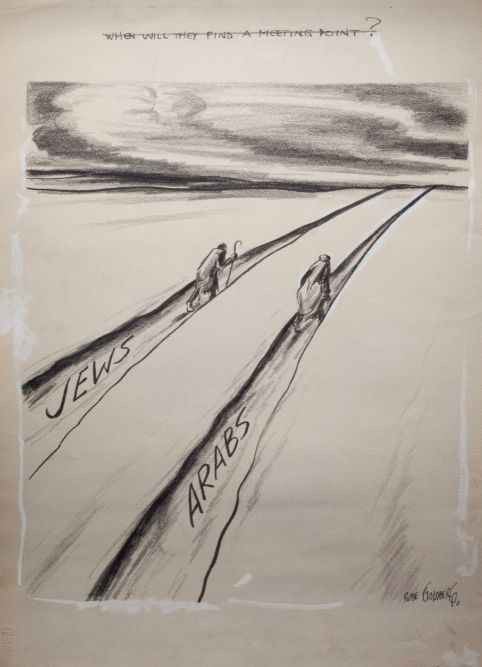

Rube Goldberg, Jews and Arabs, 1947. © Rube Goldberg Inc. Courtesy of the National Museum of American Jewish History.

Goldberg’s education may have given him a unique perspective on these misadventures. He was born and raised in California, and spent much of his spare time drawing and painting. After graduating from UC Berkeley in 1904 with a degree in engineering, he worked for the water and sewer department of San Francisco. An offer from the San Francisco Chronicle—at the time, the largest periodical on the West Coast—proved too tempting to ignore, and Goldberg became the paper’s sports cartoonist. In 1907, he accepted a staff cartoonist job at the New York Evening Mail, where he’d stay for many years, eventually becoming one of the earliest beneficiaries of mass syndication. By the end of World War I, “Rube Goldberg machines”—always credited to the artist’s protagonist, Professor Butts—could be found in the pages of hundreds of newspapers, and Goldberg was regularly billed as the nation’s most popular cartoonist.

What was it about these weird machines that appealed to so many early 20th-century readers? Goldberg grew up in an era when a swarm of gadgets big and small—telephones, light bulbs, automobiles, zippers—were beginning to intrude upon the lives of ordinary Americans, who must have responded with the same blend of wonder, suspicion, and exasperation that Goldberg evoked in his cartoons. His percussive, physical sense of humor, furthermore, proved popular at a time when slapstick comedy ruled the silver screen—in fact, Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936) features a whole series of Goldberg-esque devices, right down to the self-operating napkin.

Much like Chaplin’s films, Goldberg’s cartoons have been interpreted as a ruthless critique of American society, a loving homage to this society—and a perplexing combination of both. Compare Goldberg’s work with that of the English cartoonist W. Heath Robinson (another early 20th-century humorist who specialized in drawing elaborate machines), and it becomes clear how cheerful—and distinctly American—Goldberg’s view of things was.

Robinson became popular in the aftermath of the Great War, when his country’s infrastructure lay in tatters and rationing was the norm. By contrast, Goldberg rose to fame during a period of unprecedented economic growth in the United States, when the burgeoning middle classes spent millions of dollars on fads and fashions. In modern parlance, a Heath Robinson machine is makeshift necessity; a Rube Goldberg machine is a whimsical luxury, almost an advertisement for what Boorstin called “the wonderful American standard of living.”

Excerpt of Peter Fischli and David Weiss, The Way Things Go, 1987. View the excerpt by clicking here

Not that Goldberg didn’t take dead aim at his country on occasion: He was, to quote Josh Perelman, chief curator and director of exhibitions and collections at the NMAJH, a “critical observer of his world during rapidly changing and tumultuous times.” Several of his cartoons from the 1930s criticize Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. In one, the then-president (unmistakably rendered with his massive jaw and clenched teeth) studies a cluster of tubes. They’re labeled with government agency names, and look as if they might have been designed by Professor Butts on a bad day—FDR seems surprised that his prized toy produces nothing more than a few drops of water. A later drawing (for which Goldberg won a Pulitzer Prize) shows a happy family perched on a massive atomic bomb that, unbeknownst to them, is teetering on the edge of a cliff. That was in 1947, two years after a team of whiz kids invented a gadget deadly enough to obliterate entire cities.

The machines Goldberg dreamed up over the course of his long career could be friendly or sinister, charmingly useless or terrifyingly efficient. Perhaps that’s why his cartoons have inspired so many different kinds of creatives—they’re inkblots, betraying the viewers’ own attitudes about science, technology, and the future. For Swiss Dada sculptor Jean Tinguely, whose kinetic art is unmistakably Goldbergian, useless machines were metaphors for the evils of capitalism, their only true function to torture the working classes. Something similar could be said for the grimy tubes and wires running through Terry Gilliam’s dystopian masterpiece Brazil (1985), which seems to take place in a world run by Professor Butts’s evil twin. And what are the rusty chains and cages in the Saw movies if not Rube Goldberg machines designed to torture their victims?

In their experimental film The Way Things Go (1987), Swiss artists Peter Fischli & David Weiss invoke another side of Goldberg’s cartoons: the hypnotic, almost Zen-like wonder they can inspire. The film—seemingly shot in one continuous, half-hour take, but actually stitched together from a series of short scenes—chases a chain reaction from one object to another: a rocket deflates a balloon, which starts a fire, which drops a marble onto one side of a lever, which sets a barrel rolling, and so on. It’s an extraordinary spectacle, the kind Goldberg spent his professional life imagining on paper, but never tried to build.

When Goldberg was born, it’s easy to forget, most of America was lit by candlelight. He died in 1970, the year after Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. The intervening period saw the greatest explosion of science and technology the world has ever witnessed. While the decades since Goldberg’s death have been just as exciting, technology has gotten less and less tactile during this time—the mechanical processes that once powered our devices have largely been replaced by invisible computer programs. The result is a legion of sleek, otherworldly objects like the iPhone, which seem simple, even when they’re a million times more intricate than Butts’s self-operating napkin.

Maybe that’s why the NMAJH’s exhibition feels surprisingly poignant at times: Rube Goldberg’s machines are unparalleled monuments to the analog era, the very last time in history when complex machines were simple enough for ordinary people to understand.

Spread the word