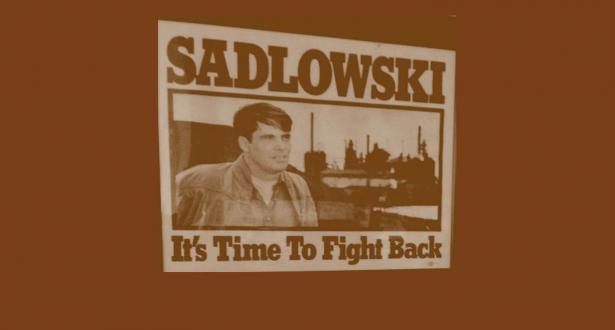

Ed Sadlowski passed away yesterday. His life is a testament to the grit of the leftwing Midwestern union militants. His roots in unionism go back to the Southern Illinois coalfields and the Steel Workers Organizing Committee of the Congress of Industrial Organizations of the 1930s. Then Ed himself led the rank-and-file insurgency that resonated in the Midwest in the mid and late 1970s. You can see his biography here.

In the summer of 2011, I was glad to hear Sadlowski’s reflections on the Wisconsin uprising. It was a joint interview with Jerry Tucker, another Midwestern insurgent in the autoworkers, who died in 2012. After a celebration of the 1877 St. Louis general strike, I asked them to reflect on the recent events. Both of these men had faced the intense red-baiting and race-baiting of official labor union leadership in the 1970s and 1980s. They had both won in the Midwest district positions in their unions, against the odds, but lost in their attempts to win the presidency of their unions. One has to wonder how history might have been altered had they succeeded. The interview was also kind of response to a Labor: Working Class Studies of the Americas interview with Andy Stern, the lead advocate of labor-management cooperation, and someone who argued that struggle-based unionism was a romantic impossibility in the present.

Rosemary Feurer (RF): What do your experiences, in the past, tell you about the present moment, about what is happening in Wisconsin?

Ed Sadlowski (ES): Wisconsin is the most important thing that has happened, equally (to) the inceptions of the CIO. If Wisconsin falls, it’s like pins in a bowling alley. If you rally to a movement, you will get the ball rolling. Why we’ve only made that limited progress, is the real question at hand.

And that question and hurdle has been in front of us for the last 200 odd years alone, not just yesterday or in Wisconsin. The labor movement has never been capable of adapting, in that sense of a long policy, of having people feel that they belong, belong to something that is right, belong to something that is fair, belong to something that creates a way to eliminate injustices, and provides a better life for their heirs to come. We’ve failed miserably in that sense. Inasmuch as we’ve tried, it hasn’t been too much of a try.

We have to learn to structure something that people can relate to, that people can be proud of being a part of . . .those emotional things. Just because someone pays dues doesn’t’ make them union. That’s what’s going on in Wisconsin, trying to collect dues on the job. There might be some good come out of that, to have a staff rep go on the site, to sign somebody up. That remains to be seen. . .We haven’t passed that knowledge on, the union as an institution, that’s our failings. To correct those failings we have to educate, agitate, organize. A lot of people have been shut out—

Jerry Tucker (JT): This is a long span of history, from the cordwainers first efforts, and we have failed to place the struggle that workers have against capital in perspective, and create an ongoing concept of struggle. The exploitation is built into the system, and it’s an automatic aspect of the system. Capital will exploit, it will exploit itself, they’ll eat each other, if there is no one else to devour. . But workers have of course, been the main course at this point all these years. The labor movement, in its various incarnations, some have been better than others. The Knights had certain attributes and the CIO had certain attributes that we could look at that were considerably better. In all cases we have failed as a labor movement, to see ourselves in this relatively eternal conflict, that by its nature exists between capital and labor, and to adapt our ability to deal with it. The recent industrial relations system was a product of struggle where workers had penetrated to the core, so they call in the safe minds of the labor movement, we’ll create an industrial relations model. From our side, it needed complacent, vertically aligned leaders. It did not need what the mass movements represented, which was horizontal, that’s where workers were engaging in self-activity, where they were lifting their own sails and flying into the face of an enemy that they could know. So capital comes along, and a little more concerned about it. The politicians were bending toward create the accommodation, the Roosevelt and Truman administrations. The labor leaders didn’t go to sleep. They offered workers a version of détente or peace, and said, we’ve got a system now. They did it to industrial, to the public sector and the service sector which was beginning to emerge during this period into unionism, but it was the industrial sector that set the stage. The Reuther administration played a significant role in moving to co-opt the energy that was there. Out of it, the ascendancy of America as a superpower, they saw the way to make tangible gains, with improvement of job security, working conditions. And so a lot of leaders, as they grew into this. When I would say in the auto plants, Why don’t we fight that, They’d say, that’s just an incidental grievance. We have hundreds of them.

ES: But that’s the most important thing in his life!

JT: This is the great “chilldown” that had already been the mode of operation. We left struggle by the wayside. And we really failed to be honest with the rank and file members, that this is an eternal struggle. It became unacceptable, tricks like red-baiting to divide us into compartmentalized groups.. At this point, we’re at a point where the opportunity to educate and to organize, does exist, unlike what was going on in the 1970s

RF: So you actually feel this is more opportune than then?

JS: Oh, yeah

ES: Yeah, I think it’s the most opportune time of my lifetime if we take advantage of it. A movement created, not an issue. Issues you’ll get your head beat in.

JT: 120,000 people showed up at the Wisconsin state capital. When the challenge became so direct, so brutish, did it take a call from on high to respond? No, the calls were in the closet. Here’s an old saying we used to use in the plant, “You can’t lead from the rear.” Were they anywhere near the front of the parade when the things began? Not from what I can tell.

RF: What do you see as the potential, given your experiences?

ES: Make more pals.

JT: Get a bigger gang.

ES: Emma Goldman, advised young workers: She said, When in Milwaukee learn how to Polka. That’s the frailty of the labor movement, they need to learn to Polka in Milwaukee. Without the labor movement, we’re dead. We’ve got to revitalize it.

JT: Unless struggle is in front of you, you wont’ get from A to B. Struggle creates the new wealth of experience. People have to believe they are the leaders we’ve been looking for, and in Wisconsin, the people who were getting paid the big bucks, they kept trying to test the winds. They were trying to figure out what compromises they could offer before negotiations began. Except as we all know, that never works. We had rank-and-file workers who stepped forward, who took initiatives. It was students like the teaching assistant unions,. Finally the leaders said oh, good, now we’ll order pizza.

RF: But the argument from the other side is that the times are different, that production doesn’t matter, that the service and public sector is different.

ES: The public service worker has had that instilled in him, that he or she’s not a working stiff. They look at that negatively, it’s like a Bob Cratchit mentality, into those guys and gals. The issue is how do we turn that around?

JT: We need to produce impetus for more new labor leaders, create new ones. It ought to be struggle orientation for a new generation. And to create our own sense of direction. A state leader in the Democratic Party of Wisconsin recently declared that collective bargaining will not be part of the issue of running for these 6 recall elections that are going on in Wisconsin right now. I responded, along with some other critics, with saying: The labor movement has got to demonstrate its determination to offer leadership in these kind of struggles, not followership. . No one in this dynamic situation should step back and let sell-out politicians who had no ideas, no concepts, produced the dilemma in the first place, all the way up to the top of the Democratic Party in Washington. Then want to step in? I’d smack the shit out of them. That’s what’s happening on the ground right now.

ES: To rebuild what you’ve got there you can’t surrender to the Democratic Party, letting the Democratic Party have part of the strategy, is what is the problem.

JT: They have a choice. …What we’re trying to do in Wisconsin is speak truth to power. What they want is the energy of the w class but they want the money of the capitalist class, to keep them afloat. We’ve faced these issues historically. Carter broke every promise, Clinton broke his promises, Obama is on the same track that has presented historically.

If workers are reorganized to sense their own power and to begin to exert it where it really counts…When they started introducting the topic of a general strike. Jim Cavanaugh my old friend in Wisconsin has introduced general strike concept. You don’t talk about a general strike, as much as, how do coordinated job actions move the ball forward and down the field. I wouldn’t use the term general strike, that’s a mythical thing.. . But the idea of worker power as a concept, even in public unions, and how you get that power, is the critical issue.

RF: Were there missed opportunities to create that power in the past?

JT: I think there were opportunities in the 1970s that did exist, and it was awfully hard to get around the leadership and legacy of red-baiting. Lane Kirkland called the Humphries Hawkins Full employment law, “Oh that’s that planning shit.” We had this much-touted labor law reform act similar to the recent EFCA, on the public policy side, in the Carter administration. What did we do? First thing we did, was send this much touted team of lawyers, including the never-lamented Steve Slossberg, among others, in to meet with John Dunlap, and modified the bill before it was introduced, to meet the objections of the potential objection is of the corporate community. As soon as it was introduced, the corporations reiterated a whole new set of objections, which of course then we had to work backwards from. But we had this organizing moment. And we rallied people all over the country. And then when we didn’t get it, we said, “oh, ok” (laughter) We didn’t do grassroots. The labor movement did not do grassroots.

RF: But they would say, we had busses to Washington, it was grassroots.

ES: But that’s not grassroots, that’s sending people to Washington. You got off the bus and then you went home.

JT: On Solidarity Day in 1981 and 1982, you went both times when nobody was in session. Craziest thing.These decisions were made by those who wanted to avoid conflict, people like Lane Kirkland.

JT: These were issues that if they had been rallied around, like in the 1930s, or like their doing in Wisconsin today, we would not be in the situation we are in today.

JT: The problem today comes from the idea that you don’t need struggle. You make progress through accommodation, but how can that be? Only if you have equal power can you accommodate. Capital doesn’t sleep and its got the whole globe as its playground. In order to wage war on a global basis like they are doing, we have to link up; a global sense of an injury to one is an injury to all.

RF: But Andy Stern would say that the only way to work this out to advantage to workers, and some workers might say, how can we really fight on a global scale where capital has such advantage?

JT: That’s the fault of leaders who didn’t describe it in more practical terms.

ES: We have to start thinking out of the box, on the issue of time, workday. We have to re-gear ourselves. The first resolution in the CIO was for a 6 hour day. That was 1937. Today they’re working 12 hours a day in steel plants. I scream this out to Wisconsin. This is not an issue oriented campaign that needs to be waged, but a movement-oriented campaign.

JT: The issue is that we’re in a class struggle. Our job is to say a worker is a worker is a worker. It’s going to require rank and file to be caught up. When workers are engaged in struggle, their ears are open. We can connect their experiences with workers in Bangladesh. We have the capacity to talk about what’s going on across the globe as part of capital’s history.

ES: To be the driving force.

JT: Then some of the leaders will get out of the way. One of them, has already quit, Andy Stern.

ES: I got worse words than collaboration, for describing him…. But we have to not focus on those types, but instead concentrate on all the people at the base who have so much unrealized potential. I look for a better tomorrow, I really do.

[Rosemary Feurer is an Associate Professor of History at Northern Illinois University. She is author of Radical Unionism in the Midwest, 1900-1950 and Against Labor.]

Spread the word