President Lyndon Johnson had established the commission to examine the disorders and violent protests in Detroit, Newark and well over 100 other American cities during the summer of 1967, and earlier. What it found was searing. “What white Americans have never fully understood – but what the Negro can never forget – is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto,” the commission concluded. “White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”

Mostly moderate and mostly white men, the members of the bipartisan panel carried the imprimatur of the political establishment. Their recommendations attracted widespread public debate. The paperback edition of the report sold over two million copies.

Occupied by the Vietnam War and concerned about the legacy of his Great Society domestic agenda, Johnson distanced himself from the “two societies” warning. But the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator Robert Kennedy strongly endorsed the commission’s findings and recommendations before they were assassinated and before more protests erupted during that traumatic year of 1968.

The Kerner Commission recommended “massive and sustained” investments in jobs and education to reduce poverty, inequality and racial injustice. Have we made progress in the last 50 years?

A Return to Segregation

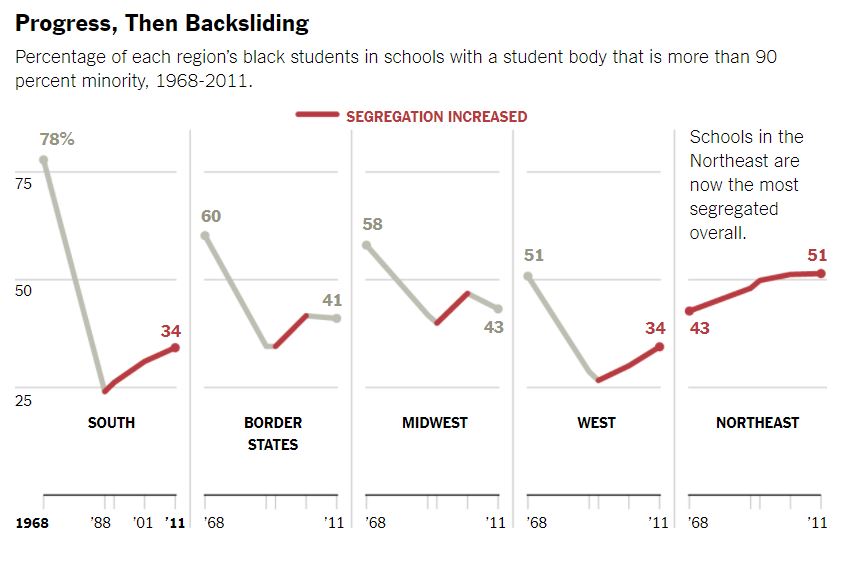

In many ways, things have gotten no better — or have gotten worse — since 1968. Public schools have been re-segregating for decades.

Today the gap between poorer and richer American students in access to qualified teachers is among the highest in the world. Fewer African-Americans have access to majority-white (read: generally better financed) schools.

We know why. One reason: When schools are released from court-mandated desegregation, that progress gradually is reversed.

Inequality That Would Shock the Commission’s Members

The disheartening percentage of Americans living in extreme poverty — that is, living on less than half the poverty threshold — has increased since the 1970s. The overall poverty rate remains about the same today as it was 50 years ago; the total number of poor people has increased from over 25 million to well over 40 million, more than the population of California.

Meanwhile, the rich have profited at the expense of most working Americans. Today, the top 1 percent receive 52 percent of all new income. Rich people are healthier and live longer. They get a better education, which produces greater gains in income. And their greater economic power translates into greater political power.

The Tragedy of Mass Incarceration

At the time of the Kerner Commission, there were about 200,000 people behind bars. Today, there are about 1.4 million. “Zero tolerance” policing aimed at African-Americans and Latinos has failed, while our sentencing policies (for example, on crack versus powder cocaine) continue to racially discriminate. Mass incarceration has become a kind of housing policy for the poor.

Fifty Years Later, We’ve Figured Out What Works

Policies based on ideology instead of evidence. Privatization and funding cuts instead of expanding effective programs.

We’re living with the human costs of these failed approaches. The Kerner ethos — “Everyone does better when everyone does better” — has been, for many decades, supplanted by its opposite: “You’re on your own.”

Today more people oppose the immorality of poverty and rising inequality, including middle-class Americans who realize their interests are much closer to Kerner priorities than to those of the very rich.

We have the experience and knowledge to scale up what works. Now we need the “new will” that the Kerner Commission concluded was equally important.

[Fred Harris, a former senator from Oklahoma, is a professor emeritus of political science at the University of New Mexico and the lone surviving member of the Kerner Commission. Alan Curtis is the president and chief executive of the Eisenhower Foundation, the private-sector continuation of the 1968 Kerner Commission and the 1969 National Violence Commission. The two are the co-editors of “Healing Our Divided Society: Investing in America Fifty Years After the Kerner Report.”]

Spread the word