On Monday in Pyeongchang, Adam Rippon and Eric Radford posed for a photo together, Olympic medals proudly draped around their necks. Rippon had delivered a powerful, artistic performance as the United States claimed bronze in the figure skating team event. Radford, a pairs skater, played a crucial role in Canada claiming gold.

Embracing for the cameras afterwards, they were united not just by their sport but by history. No openly gay male athlete had ever reached a Winter Olympic podium before. Now, there were two.

With Rippon’s innate star quality marking him out as an early darling of these Games and Radford quietly picking up a second medal after finishing third in the pairs competition with partner Meagan Duhamel, some have remained puzzled why their sexuality has remained such a dominant talking point. But the answer could be found once Radford posted the image of him and Rippon to Twitter.

It was a timely reminder that even though Rippon and Radford’s stories are about the present and future, they’re also about the past. Because, for a sport that revolves around individuality and expressiveness, figure skating has a rather complex history with gay athletes.

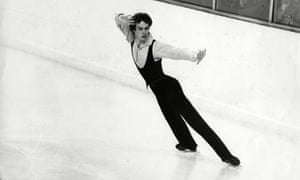

It was 42 years ago and in the immediate aftermath of winning gold in Innsbruckthat Britain’s John Curry faced down a roomful of the world’s media and fielded questions about his “very personal lifestyle”.

Before competing, he had given an interview to American journalist John Vinocur of the Associated Press. It was an open conversation and Curry spoke about being gay. After his mesmeric performance and subsequent triumph, the article was published and the conversation changed. Curry’s sexuality, not his radical and revolutionary skating or his alluring artistry, was quickly pored over. There was a salacious quality to various headlines. Some newspapers, perhaps worried about what their readers would think, tried hard to avoid using words like “gay” or “homosexual” at all. It just seemed less troublesome to say things like “effeminate” instead. After all, to the many in the press the point remained the same: he was an outlier.

So proud that @Adaripp and I get to wear these medals and show the world what we can do! #represent

#olympics #pyeongchang2018 #pride #outandproud #medalists #TeamNorthAmerica

Curry later maintained that his words were off-the-record. In an emotional TV interview in 1987, he recounted the experience to the BBC’s Barry Davies.

“A lot of people said I ‘came out’ at the Olympics but I didn’t,” said Curry. “I never intentionally set out to make a statement. But this man, John Vinocur, had made it appear that I wished I had done just that. And, of course, then having done it I’m not going to turn around and say that a) it’s not true or b) that I think it’s wrong or I’m ashamed of it, which was not the case. I had simply allowed myself to be conned by a journalist.”

In Bill Jones’ excellent biography, Alone: The Triumph and Tragedy of John Curry, he suggests the skater was aware of what he was doing, because he was so tired of carrying around the burden of secrecy for so long.

The frenzy surrounding Curry’s admission meant that a crucial, harrowing part of his story was glossed over. What he also described to Vinocur was the relentless desire of others to change him. To others in the skating community he was too flamboyant, too offensive, too different. People would start talking. They wanted to control him, program him so he could conform.

John Curry was one of the great figure skaters of his era. Photograph: REX/Shutterstock

“When I started to skate I had a coach who used to grab my arm and push it back to my side when I finished a movement with it in the air,” Curry said. “This man wanted me to skate in a certain way and when he didn’t, he beat me. Literally beat me. And there were more humiliating things. He sent me to a doctor as if there were something to treat.”

One coach, after Curry parted ways with him, warned: “You will never make it as a skater or as a man.”

Curry was left isolated after Innsbruck. He was deemed a “haunted hero” and if there were other gay figure skaters on the circuit, none followed his lead and went public. Even into the mid-1990s, high-profile male skaters who were deemed ‘different’ were still warned against pushing the boundaries

Rudy Galindo, a gay Mexican-American, was a champion pairs skater and won back-to-back US titles with his partner, Kristi Yamaguchi. In 1996, after switching to singles skating, he claimed a memorable gold at the US Championships in his hometown of San Jose and followed that up with a bronze medal at Worlds.

Like Curry, he had remained true to himself, regardless of how much it irritated others. “I was told by the authorities within my sport to skate in a certain masculine way,” he tells the Guardian. “My sometimes controversial costumes were hyper-analyzed by authorities in the sport. Because I was openly gay at a time when it was most definitely not politically correct, I felt as if I was constantly under the microscope. As the power brokers within my sport tried to contain me, I was equally steadfast in attempting to break through the barriers and show the world who Rudy Galindo truly was, and is to this day. It seemed like an eternity. I felt like an island in an open sea.”

Eric Radford picked up his second medal of the Games alongside Meagan Duhamel. Photograph: Jeon Heon-Kyun/EPA

But, he got there eventually. And made a substantial statement too.

It was at the World Championships in Edmonton in 1996 when Galindo took to the ice for his gala exhibition. Dressed all in black and skating to Ave Maria, he wore a huge red ribbon around his neck that extended all the way to his midriff. The performance was a tribute to anyone affected by the Aids epidemic and dedicated to his brother and two former coaches, all of whom succumbed to the disease in the space of just six painful years.

In 1994, at the age of 44, Curry had also died from Aids, as did many more skaters. In 2000, Galindo was himself diagnosed as HIV positive but, showing the same grit and determination he displayed as an athlete, continues to thrive as a successful coach in California.

In recent days he’s been immersed in Rippon and Radford’s successes and believes it’s a seismic time for the sport. “This is, most certainly, a defining period for figure skating and gay athletes,” Galindo said.

“I believe it’s truly a watershed moment and a long time coming, I might add. The contrast to when I was competing is like night and day. Unfortunately, being gay was taboo. But finally, there is vindication. Vindication not just for me, but vindication for my beloved gay community. I applaud Adam and Eric. I am rejoicing that the world is beginning to accept gay athletes for who they are. I love it.”

As the only male skater in a tiny hockey town in northern Ontario, Radford was bullied relentlessly as a child. He came out publicly in December 2014, motivated by the possibility that, somewhere out there, a young kid would be able to see somebody on TV who was openly gay, 100% themselves, and be inspired by it.

Earlier this week, via his agent, Rippon received an email from an 18-year-old gay man from just outside Detroit. Dealing with his sexuality had been a struggle for him and his family. But, he’d read Rippon’s story, seen his unabashed openness in Korea and felt the need to say thanks.

More than four decades after Curry’s sexuality was treated with suspicion and followed by relative silence, figure skaters are now stepping up, speaking out and not just inspiring future generations but past ones too.

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

I appreciate there not being a paywall: it is more democratic for the media to be available for all and not a commodity to be purchased by a few. I’m happy to make a contribution so others with less means still have access to information.Thomasine F-R.

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps fund it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as $1, you can support the Guardian – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

Eric Radford

Eric Radford

Spread the word