Charlotte Cops Dig In, Won't Release Video; Opposition to Police Terror Builds; The Shattering of Charlotte's Myth of Racial Harmony

- Charlotte Cops Dig In, Won't Release Video; Opposition to Police Terror Builds - Sarah Lazare (AlterNet)

- 5 Things to Know About the Unrest and State of Emergency in Charlotte After the Police Killing of Keith Lamont Scott - Janet Allon (AlterNet)

- The Shattering of Charlotte's Myth of Racial Harmony - David A. Graham (The Atlantic)

This is clear in Charlotte, North Carolina, this week, where intense demonstrations and riots have followed the shooting of Keith Lamont Scott by a police officer on Wednesday. The banking mecca—the Southeast’s second-largest city—has tended to see itself as an avatar of modernity and moderation in a state where both are uneven. Although Uptown’s gleaming skyscrapers and chain restaurants seem to suggest a city that is both without, and untethered from, history, the Queen City was built on slavery and its racial politics remain fraught, just like those of nearly every other city. It struggles with a history of segregation, racial tension, and difficult relations between African Americans and their police department.

Charlotte does have a history, one that stretches back to before the American Revolution; Mecklenburg County claims to have declared independence from Britain way back in 1775, though historians aren’t sold. At one time, it was just another small Piedmont town. That changed when railroads came through in 1852, transforming Charlotte into a central hub for the plantation economy. The ability to easily move the produce of the slave economy out of the region and to markets transformed the village into a prosperous hub, its population more than doubling between 1850 and 1860. On the eve of the Civil War, Mecklenburg County had nearly 7,000 slaves, accounting for about 40 percent of the population.

After the Civil War, African Americans briefly gained political power in North Carolina, but by 1900, Democrats had returned to power and purged blacks from government.

Charlotte was not at the forefront of protests during the height of the civil-rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Greensboro, with a large, middle-class black population and North Carolina A&T University, took the lead. Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools desegregated after Brown v. Board of Education, with Dorothy Counts enrolling at Harding High School, an all-white school, in 1957, surrounded by jeering whites. A photo ran in newspapers around the country.

By 1965, however, there were still 88 segregated campuses. That year, a black couple wanted to send their son James Swann to an integrated school, and were refused. The NAACP Legal Defense Fund sued the Board of Education, with the case eventually going to the Supreme Court six years later. The justices ruled that busing was an appropriate remedy for racial imbalances in school districts.

What followed in Charlotte was a surprisingly successful experiment. The city undertook busing, producing a school district that was both well-integrated and produced strong student outcomes. In stark contrast to violent and deadly riots in Boston over busing, Charlotte was widely known as “the city that made desegregation work.” In the meantime, Charlotte was becoming a gleaming, corporate city, home to corporate giants like Bank of America, Wachovia, and Duke Energy.

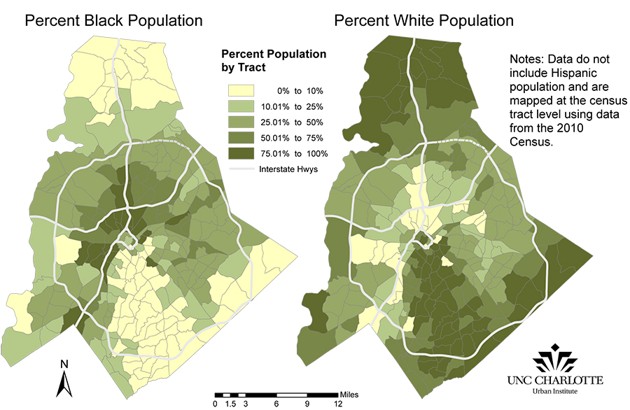

Racial Population of Mecklenburg County, 2010 Census

A 2014 paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics explored the results of the shift:

In September 2013, a black man named Jonathan Ferrell was in a car crash in Charlotte in the early hours of the morning. Seeking help, he banged on the door of a house. The resident called police, who shot Ferrell when they arrived. He was unarmed. The white officer who shot him 10 times, Randall Kerrick, was tried for involuntary manslaughter, but the case ended in a hung jury. Kerrick resignedfrom the police force under an agreement. The city also reached a $2.25 million settlement with Ferrell’s family.

A review by The Charlotte Observer in 2015 found that few officers were disciplined for shootings of civilians, even when the city was paying out large settlements:

Putney has been outspoken about racial issues, weaving in his own experiences as both a black man and a cop.

“Even now when I see blue lights, it hits me in the stomach. I’ve had that reaction since I was eight years old,” Putney said in July, after police officers were killed in Dallas. “But what you don't know is I'm sometimes more fearful when I put this uniform on. I'm gonna tell you a secret, I'm always black—I was born that way, I'm gonna die that way, but I chose to put myself in harm's way with the honorable people who wear these uniforms to protect the people who need us most.”

Recently, the city has worked to cut a more progressive profile. Governor Pat McCrory, a Republican, previously served as mayor of Charlotte, operating as a pro-business moderate, though he has governed the state as more of a conservative. The current mayor, Jennifer Roberts, is a Democrat. In 2012, Charlotte hosted the Democratic National Convention. In early 2016, the city passed an ordinance banning discrimination against LGBT people and requiring that businesses allow transgender people to use the bathroom corresponding to the gender with which they identify.

In response, the state General Assembly entered a special session and passed HB2, a controversial law overturning the local ordinance and banning other cities from passing their own. It also required transgender people to use bathrooms in public facilities corresponding to the sex on their birth certificate. The backlash to the law has cost the state millions of dollars in economic benefits, many of which would have helped Charlotte, including the 2017 NBA All-Star Game. The contest will be played in New Orleans instead.

The LGBT ordinance highlighted Charlotte’s unusual position in the state. While North Carolina’s cities tend to be far more liberal than rural and suburban areas, this battle represented either Charlotte trying to lead the city in a more progressive, just direction (as its boosters argued) or the latest evidence that Charlotte was a self-righteous metropolis separated from the rest of the state.

It is true that the Queen City has tended to see itself as more progressive and less troubled by the old bonds of race than other cities, which is one reason the riots have shocked residents so much. In July, after the Dallas killings, Putney touted Charlotte’s efforts to fight racial bias.

“We're different in Charlotte, y'all,” he said “And we're a good kind of different. We're a good kind of different.”

It turns out Charlotte wasn’t as different as it believed.

[David A. Graham is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where he covers U.S. politics and global news.]

Spread the word